Darfur conflict: Sudan's bloody stalemate

- Published

A decade after the disastrous war in Darfur began, there is no end to sight to the fighting.

The intensity of the conflict in Sudan's western region has diminished since its early years, but most of Darfur is still extremely dangerous.

More than 1.4 million displaced people still rely on food handouts in camps throughout Darfur, and many others have fled the country.

The multi-layered conflict has also done colossal damage to Sudan's image: The US and many Western activists have accused the government of genocide.

Even before the war broke out, Darfur was in trouble.

Like many of the regions on Sudan's periphery, it was underdeveloped and politically marginalised.

Diminishing rainfall over decades had made life precarious in Darfur, leading to recurring food shortages.

Surprise

There were frequent clashes between ethnic groups, often over "hakurat" or land rights.

In the late 1980s, an Arab supremacist movement emerged, allegedly backed by Libya's Muammar Gaddafi.

Identity in Darfur is both fluid and complicated, but African groups like the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit felt the government was taking the side of the Arabs.

Religion was not an issue: Almost everyone in Darfur is Muslim.

The beginning of the war is usually given as 2003, though rebel movements had been been formed before that.

In April 2003, rebels struck the airport of Fasher, capital of North Darfur.

The surprise raid through the desert - a tactic which became characteristic of the fighting in Darfur - was astonishingly successful. The rebels destroyed seven planes, and captured the head of the air force.

Khartoum - and the world - realised something serious was under way.

The Sudanese government's response, which relied on air power and an Arab militia known as the Janjaweed, has been described by the Sudan expert Alex de Waal as "counter-insurgency on the cheap".

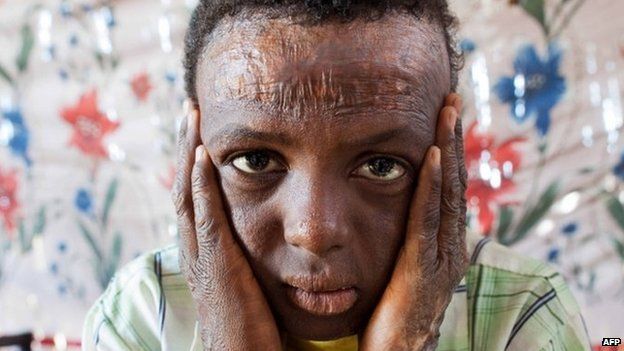

Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit villages were bombed and burnt, civilians were killed, and women were raped.

Warrants

In 2008, the UN estimated that 300,000 people had died because of the war, though Khartoum disputes the figure.

Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed in Darfur.

The genocide charge alleged that he had overseen an attempt to wipe out part of the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit communities.

Mr Bashir was the first sitting head of state to be the subject of an ICC arrest warrant.

He, and the other senior officials facing similar charges, have denied all the accusations.

There is no doubt that the ICC arrest warrants have profoundly altered Sudan.

The West wants nothing to do with President Bashir or his government. Diplomats will not meet him, and there is little chance of Sudan getting its crippling debt forgiven or US sanctions removed as long as he is in power.

However, the ICC charges actually increased the president's popularity in Sudan and some Arab and African countries.

They were seen as an affront to Sudan's sovereignty, and in some cases as an attack on Islam by the West.

Mr Bashir has not been arrested, and there seems little prospect of him facing trial any time soon.

Common image

The war drags on, too.

A 2006 peace agreement was signed by only one of Darfur's many armed groups, and this subsequently went back into rebellion.

In 2011, a minor rebel coalition signed the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD), and a splinter movement from another rebel group added its name recently.

The DDPD promised wealth and power-sharing, development for Darfur, and compensation for those who had suffered during the war.

So far, most of this has not happened.

Three rebel groups continue to fight the government: Two Sudan Liberation Army factions, led by Abdul Wahid al-Nur and Minni Minawi; and Gibril Ibrahim's Justice and Equality Movement (Jem).

In late 2011, the three joined up with the SPLM-North rebels, who operate in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states, in a loose alliance known as the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF).

The UN has accused South Sudan of supporting the SRF, in particular by hosting Jem on its territory, though Juba denies the charge.

The formation of the SRF scared Khartoum, but it has not yet changed the military picture substantially.

The Darfuri rebels operate in an archipelago of no-go areas in Darfur, and sometimes further afield.

Thaw in relations

This is no longer a simple war between rebels and the state, however, and it has not been for some time.

In some years, the biggest contributor to the violent death toll in Darfur is clashes between different Arab groups.

Some smaller African groups have fought for Khartoum, despite the common image of the war as one between African rebels fighting against the government and the Darfuri Arabs.

Criminality has increased all over the region.

Ten years after it began, Darfur's messy, bloody stalemate persists.

The civil war is best understood as a conflict conducted on several levels at once:

- On the local level, groups battle each other, usually over resources

- On the national level, rebels challenge the state

- On the international level, Sudan's neighbours and the world's great powers often react to Darfur through the prism of their own national interests.

President Bashir is convinced the US is attempting to overthrow him, while Sudan relies on Chinese and Russian support in the UN Security Council.

At different points, Chad and Libya supported the Darfuri rebels, and Khartoum helped armed rebellions in those countries too.

Khartoum is now on better terms with Ndjamena and Tripoli.

If the current thaw in relations with Juba continues, the Darfuri rebels might find life more difficult.

But Darfur's problems will not end until a remedy is found for the underlying causes of underdevelopment, political marginalisation, and dwindling resources.