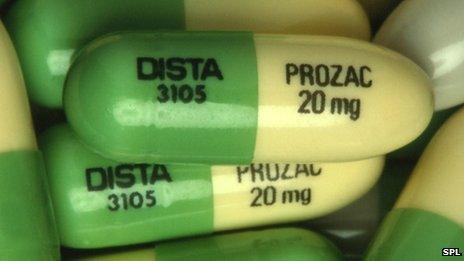

How Prozac entered the lexicon

- Published

Twenty-five years after Prozac was introduced, the name has entered the cultural lexicon and helped define how people think of mental illness.

Back in the 1990s Prozac achieved what few prescription drugs ever do. It was trendy.

The drug found fame among laymen, fuelled in part by Elizabeth Wurtzel's bestselling book Prozac Nation. Now it is part of the everyday lexicon.

The drug was introduced in the US in 1988 and in the UK the following year. Since then, it has become a cipher for discussions about mental illness and whether it should be treated by the talking cure - therapy in which a patient works things out with the help of a professional - or with drugs.

"It was like bringing a meat cleaver down," says novelist Sarah Dunant, co-editor of an anthology of essays, The Age of Anxiety. She has a personal experience with antidepressants - saying they helped her through a tough time years ago.

She believes Prozac has had far-reaching implications. "Things are not the same now as they were before."

Not everybody is happy about that. "What made Prozac good was not that it was potent, which it really was not, but that it had really good marketing," says David Healy, a professor at Cardiff University and the author of Pharmageddon.

"They made us overcome the natural caution most of us have about pills and convince us that we absolutely had to have these things," Healy says.

The marketing plan was subtle. Manufacturer Eli Lilly picked a name created by Interbrand that aimed to distance the drug "from everything typically associated with anti-depressants - strong chemicals, side effects".

Prozac - as both a drug and a concept - caught on. Prozac Nation had a cult following. It was reissued in 2002, pegged to a movie starring Christina Ricci and sold more than 120,000 copies that year, according to Publishers Weekly.

Through books and movies, Prozac gave an almost chic gloss to mental illness in some people's eyes. After Prozac Nation was published, Wurtzel "went home with a different man every night and did heroin every day", she wrote recently in New York Magazine.

Prozac, which now acts almost as a shorthand for all anti-depressants, appears in the Oxford English Dictionary. People can have a "Prozac moment", which means fleeting happiness - or forgetfulness. They can also have a Prozac shot (sambuca and schnapps).

Not surprisingly, Prozac has also become a source of material for film directors. In Steven Soderbergh's psychological thriller Side Effects, a New Yorker takes pills for depression - and Prozac is inevitably mentioned.

The drug has seeped into pop culture, and also the lives of ordinary people. Today, Europeans and Americans take antidepressants at roughly the same rate. In 2010, one in 10 people in Europe had taken them, according to the Institute for the Study of Labour in Bonn. In the US, 11% of people over the age of 12 take antidepressants, according to the US Centers for Disease Control research.

It's easy to conclude that the public image of Prozac has helped fuel social acceptance of antidepressant use.

But plenty of those who have prescribed drugs can be critical of the way they have been used. "There was this whole idea that Prozac made you better - well, I wasn't sure," says Joanna Moncrieff, now a senior clinical lecturer in neuroscience at University College London and author of forthcoming book The Bitterest Pills.

Moncrieff worked for years with patients in a 22-bed ward at a Brentwood mental hospital. "I spent a lot of time in the ward reducing medication," she says. "The staff called me The Slasher."

Not everybody should be taking medication, she says. "A hundred years ago if you didn't feel good, you wouldn't have expected it to be eliminated."

Still, she knows people will continue to take antidepressants. Just as Viagra has changed lives - and provided fodder for late-night comedy skits - Prozac has altered the national discourse about mental illness.

Many experts believe antidepressants are useful. Manchester University's Ian Anderson, a professor of psychiatry, says that people should not take a dogmatic approach to the drugs.

"In the end it's about getting on with your life," he says. "I've seen enough people just struggling along with depression. That doesn't seem fair."

Dunant says antidepressants once got her through a bad breakup. She says she wishes the drugs were around when her father, a manager in the airline industry, suffered a breakdown in the 1970s. He had to undergo electroshock therapy.

"It would have helped him through the most terrifying fall through the darkness," she says.

Many people feel better when they are on the drugs. But the precise mechanism is still not apparent. Antidepressants have an effect on serotonin levels in the brain, which seem to be related to emotional well-being. Yet the relationship between serotonin and happiness remains unclear.

"We're a bit blind about this," says University of Bristol's Stafford Lightman. Researchers do not have an animal model to study the effects of the drugs. "There is no such thing as a depressed mouse."

"Consequently, there are leaps of faith when you take these drugs," he says.