Pakistan health workers targeted over Bin Laden death

- Published

Few telephone calls can be as portentous as the one Mumtaz Begum, 35, received on 15 March 2011.

At the time, it sounded like just another call from a supervisor to a health worker inviting her to a meeting the next morning about a forthcoming vaccination campaign.

As it turned out, Ms Begum and 16 other lady health workers (LHWs), as they are known locally, were to become pawns in the hunt for the world's most wanted man, Osama Bin Laden.

They have since been living under constant fear of attacks, have been called traitors by some and have lost their jobs.

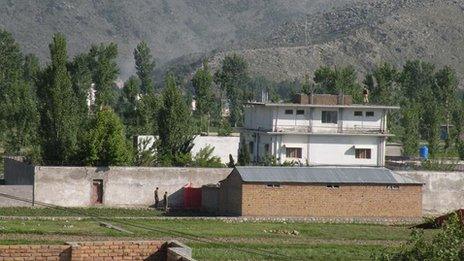

Bin Laden was killed by the American Navy Seals in a secret operation in Abbottabad, a city in Pakistan's north-western Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, on 2 May 2011.

Later that month, Pakistani intelligence services arrested a provincial health department official, Dr Shakeel Afridi, whom they accused of leading the American CIA to Bin Laden by collecting DNA samples from his Abbottabad hideout under the cover of a fake vaccination campaign.

In February 2012, the KP health department sacked all 17 health workers who had participated in that campaign, accusing them of working "against national interest".

Mumtaz Begum hardly looks the spy type though.

She lives in a dingy two-room house in Abbottabad.

The walls are unplastered, and the roofs are sagging. One of the rooms has no door.

In the second room, a portion of the wall is covered with large health department posters promoting family planning, primary healthcare and immunisation - a sign of how central her work has been to her life.

The youngest of three brothers and three sisters, she is the only one who puts food on the table. All the rest are unemployed.

And none of them is married, which is unusual in Pakistan, and a sign of the family's chronic financial woes.

Since 1996, when she joined the KP health department as a health worker, she has been able to provide food and clothing for the family.

But there hasn't been enough money to get treatment for her mother, who she says is blinded by a cataract, or for one of her sisters who is epileptic.

"Now that I've lost my job, we can't even afford two square meals," she says, breaking into tears.

While Ms Begum is financially broke, others have lost both income and health.

Dr Afridi's 'inner circle'

"I was the woman with the strength of seven men, but now I'm afraid if I stumble, I'll fall," says 49-year-old Akhtar Bibi, invoking a local proverb.

She was believed to be part of Dr Afridi's "inner circle" during the campaign, and one of two health workers who actually entered Bin Laden's hideout to obtain blood samples from the residents.

The duo are also said to have been picked up by the ISI intelligence service for questioning after Dr Afridi's arrest in May 2011.

She denies both claims, but does admit she was questioned by secret agents at several places - at the health centre, at her home and at her uncle's residence.

"It was during those days that I started to have hypertension. It got worse when my husband left me and went to live with his second wife. He says I've become stigmatised," she says.

She now works as domestic help for a little over $1 a day to make up for the income she lost when she was sacked.

So what did the health workers do wrong?

"Dr Afridi didn't drag us out of our homes. We were sent to work for him by the department," Ms Bibi says.

"At the meeting on 16 March 2011, several senior department officials were present, including our supervisor and the additional district co-ordinator. They introduced Dr Afridi as the programme co-ordinator."

Dr Afridi gave them a detailed briefing. He wanted to run a door-to-door campaign to immunise women between 15 and 49 years of age against Hepatitis B. He said the campaign would concentrate on the two adjoining localities of Nawanshehr and Bilal Town in Abbottabad.

Akhtar Bibi says the first leg of the campaign, which was held on 16 and 17 March and involved 15 health workers, mainly covered Nawanshehr.

This is the area where another al-Qaeda leader, Abu Faraj al-Libbi, had narrowly escaped arrest by Pakistani intelligence operatives in 2004.

She says two more campaigns followed - from 12 to 14 April, and again from 20 to 21 April.

The last one entirely focused on Bilal Town, where the lair of Bin Laden was located.

"Nine LHWs working in groups of three covered Bilal Town in two days. Dr Afridi personally supervised that campaign. He had hired two vans for us, and was himself using an official car of the KP health department," she says.

She was one of the two health workers who, in the presence of Dr Afridi, called at the Bin Laden compound on 21 April, but says no one came to the door.

She says she is not aware if Dr Afridi got the samples in the end, but remembers him saying it was "very important to immunise people in this house".

Few believe any of the women had any idea about Dr Afridi's aims. There are also questions over whether Dr Afridi knew what he was looking for, or was just following instructions.

In a petition filed last year, the health workers pleaded that senior officials in the health department made them the "scapegoat merely to save their own skin".

Last month, the court ordered their reinstatement.

But health authorities say they have not yet decided whether to appeal against the order or comply with it.

They may or may not get their jobs back, but it is unlikely they will be able to live without fear for a long time.

Most of the health workers I contacted refused a meeting. Others refused to be photographed or be interviewed on tape.

It took considerable persuasion for Akhtar Bibi to agree to speak with me, and then she insisted we meet at a secret location, which we did.

"My life is in danger," she explained. "Our lives are in danger. They never used to kill health workers before Dr Afridi's campaign."

- Published18 December 2012

- Published24 May 2012

- Published11 September 2012

- Published10 September 2012

- Published2 May 2011