Pakistan elections: Five reasons the vote is unpredictable

- Published

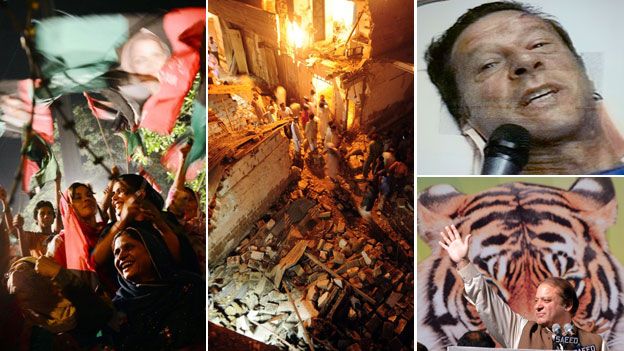

The 11 May elections will be different from any that have been held in Pakistan before. And it's not only because for the first time an elected government will finish its term and hand over power to a democratically elected successor.

For decades Pakistani politics has consisted of a series of military regimes interspersed with governments run by two parties: the Bhuttos' Pakistan People's Party (PPP) and the Sharifs' Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N).

And as millions of Pakistanis have repeatedly complained, the PPP and the PML-N have been little more than family businesses generating vast fortunes for a tiny and fabulously rich ruling elite.

But this election contains new, unpredictable elements.

1. Imran Khan

The cricketer-turned-politician, long dismissed as a political no-hoper, has mounted a serious challenge. Before he fell off a lift and injured his back, he was storming around the country, holding as many as seven mass rallies in a single day.

Privately, government officials say that their internal polling suggests that Mr Khan's PTI will win a significant number of seats.

As the change candidate, Imran Khan draws significant support from disparate groups.

His most vocal support comes from young people, many of them vowing to vote differently from their parents.

He also appeals to liberals who hope that, at heart, his days as a Westernised, high-living playboy are not really over.

But equally significant is his appeal to the middle classes, many of whom have tended not to vote in recent elections.

The economic growth of the Musharraf years increased the number of property-owning Pakistanis. They tend to be conservative, anti-American, pious, nationalistic and infuriated by the venal upper classes.

Imran Khan's campaign speeches have reflected all their attitudes.

2. New voters

A new electoral roll has injected another element of unpredictability. A reinvigorated Electoral Commission has overhauled the lists of those eligible to vote.

There are now 85 million verified voters. Since the last election, the commission has removed 37 million bogus names and added 36 million new ones.

Of course some things remain the same.

In many parts of Pakistan such as interior Sindh, Balochistan, southern Punjab and parts of the north-west, traditional feudal and tribal structures remain in place and the electorate there is expected to follow traditional voting patterns.

It means the election will be decided in the country's richest province, Punjab. In many Punjabi constituencies there are now three way contests between the PTI, the PPP and the PML-N, making the results highly uncertain.

There is a widespread expectation that nationally no one party will win an overall majority and whoever emerges as the leader of the biggest party will have to put together a coalition.

3. Taliban threat

Whilst the country's major politicians slug it out on the campaign trail, there are also deeper trends affecting these elections.

The Taliban insurgents are more confident than ever before.

During the last election campaign, in 2008, they observed a ceasefire. This year they are openly calling for the overthrow of the democratic system and attacking politicians from the parties which criticize them. So far bombings and shootings have killed more than 100 people in election-related violence.

Whilst the jihadis are both visible and aggressive, there are other emerging power centres.

4. A resilient judiciary

In the past Pakistan's judiciary tended to acquiesce to whoever was in power.

Although judges are still intimidated by religious extremists, they are increasingly willing to confront the politicians. And there are signs they are even daring to stand firm against the army.

General Musharraf's decision to return to the country has caused deep frustration in the military leadership. It is nervous that the Musharraf case might set a precedent in which senior officers face trials in civilian courts.

Behind the scenes the army is pressuring the courts to allow Gen Musharraf to leave the country on the grounds that he needs to see his ailing mother in Dubai. So far the judges have refused to comply.

If the judges stand firm they could establish a significant disincentive for future coups.

5. Media power

It's not just the judges who are flexing their muscles.

With sensational minute-by-minute news coverage, the satellite TV stations have emerged as a major power in the land.

With the ability to deploy journalists and camera crews all over the country and to go live to cover even the smallest incident at a moment's notice, they should make it much harder for anyone to fix the election results.

Pakistanis are now using their mobile phones to film abuses by the ruling elite. In a recent by-election one politician was filmed slapping the election officials counting the vote. The clip was repeatedly played on news channels, provoking demands for the politician to be disqualified from sitting in any assembly.

Pakistan faces many deep crises. After the Nato withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014 the economy will be starved of billions of dollars' worth of foreign aid. Power cuts are now so common that it is difficult for factories to function properly.

Jihadis, as well as openly attacking democracy, are increasingly mounting sectarian attacks and persecuting minorities.

Partly because economic issues are a more immediate concern, many Pakistanis dismiss the jihadi challenge, explaining it away as only a reaction to the US presence in Afghanistan. In fact it is an internal, ideologically driven revolutionary uprising aimed at taking over the state.

Pakistan has defied many dire predictions in the past. Many in the elite and the middle classes remain confident they can hold the line.

But some concede that keeping the jihadis at bay may require outside help.

"Let's face it," one senior civil servant put it to me. "Can the world really afford to allow a nuclear power to fall into the hands of the crazies?"

Owen-Bennett-Jones presents Newshour on the BBC World Service.