What Liberace reveals about the march of gay rights

- Published

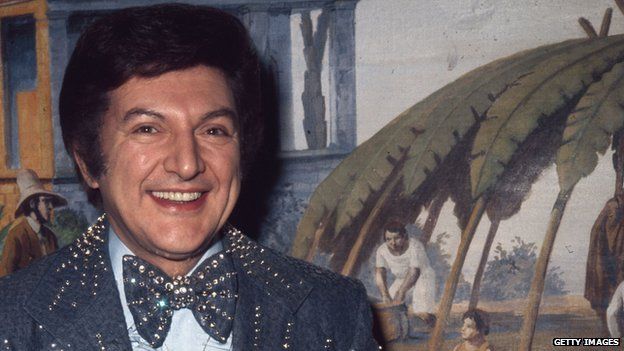

A film tells the story of Liberace's relationship with his lover, but the flamboyant pianist stayed in the closet all his life. How did he maintain this fiction, and what does it say about America's rapidly changing attitude to gay rights?

A handsome young valet helped Wladziu Valentino Liberace step from his chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce on to a stage shimmering with candelabra, and the man who called himself Mr Showmanship showed off his 16ft-long rhinestone-studded fox fur cape.

"Well, look me over," he told the audience before sitting down to play his mirror-bedecked piano. "I didn't get dressed like this to go unnoticed."

His grand entrance at New York's Radio City Music Hall in April 1984 was as cheerfully, flamboyantly camp as his fans had come to expect from his 50-year musical career.

But until his death in 1987, Liberace insisted he was not gay.

He staged relationships with women and repeatedly asserted his heterosexuality in interviews, once talking about his ideal female partner. He even famously took the Daily Mirror to court when it hinted otherwise.

His fans - typically suburban middle-aged women - seemed happy enough to accept his story. Thousands were outraged during his brief engagement to a younger woman.

It was a fiction. Behind The Candelabra, a forthcoming film starring Michael Douglas, tells the story of Liberace's long-standing relationship with his former chauffeur, played by Matt Damon.

While modern audiences are familiar with a diverse range of gay and lesbian personalities, Liberace rose to prominence at a time when camp and homosexuality were commonly and erroneously seen as synonymous.

He grew up in a conservative, working-class, Polish-Italian mid-western household, at a time when homosexuality was punishable by up to 10 years in prison in some US states.

As a result, he had good cause to fear that exposure of his private self would almost certainly have meant the end of his career.

But paradoxically, his camp, over-the-top performance style appears to have been key to his appeal to middle America. Shortly after his television programme, The Liberace Show, launched in 1952 he attracted up to 30 million viewers an episode.

A decision by the pianist during the late 1950s to adopt sober Brooks Brothers suits and jettison the candelabra coincided with a sharp downturn in his popularity.

His career bounced back after he adopted his Mr Showmanship persona during the early 1960s, declaring that "it was a shame to waste [his] mother-of-pearl trimmed suits".

According to his biographer, Darden Asbury Pyron, Liberace carefully constructed every aspect of his image to maximise his public appeal, and that included allusions to his sexual orientation.

"He always played around the edges of it, and that's part of the story of his success," says Pyron.

"But the gay stuff is only one context for understanding Liberace. It's secondary to the fact he was a great performer, he was extremely fastidious about his presentation and he gave his audiences exactly what they wanted."

More importantly, his performance style was constructed to be as non-threatening as possible. While camp, it was shorn of any suggestion that he might ever want to actually have sex.

Kevin Kopelson, professor of English at the University of Iowa, who analysed the Liberace phenomenon in his book Beethoven's Kiss, compares the pianist's public persona to that of Michael Jackson. Both men, he says, portrayed themselves as childlike and innocent.

"Liberace tried to come across as pre-sexual, non-sexual or asexual," says Kopelson. "He presented himself as a girly boy, not a gay man."

It was not enough to prevent rumours circulating, however, and Liberace felt obliged to take legal action against publications which suggested he might be gay.

Most famously, he sued the Daily Mirror over an innuendo-laden article by William Connor, who wrote under the pen-name Cassandra, which described the musician as "the pinnacle of masculine, feminine, and neuter... a deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavoured, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love".

The Cassandra article might be considered too homophobic to be published in a national newspaper today, and the 1959 trial that followed reveals much about the very different social attitudes of the time - not least in the repeated use of the term "homosexualist" during the case.

Under oath, Liberace testified that he was not gay and had never taken part in homosexual activity. The jury found in his favour, awarding damages of £8,000.

"I don't think the trial either helped the cause of gay rights or hindered it," says Revel Barker, author of Crying All The Way To The Bank, which tells the story of the case.

"People like my parents, who were big fans of Liberace, didn't really think of him as a homosexual before or after - they just thought he was a great performer."

But the Cassandra trial, coupled with his repeated denials of his homosexuality, was one reason why sections of the fledgling gay rights movement increasingly viewed Liberace with antipathy.

Aged 50 by the time the Stonewall riots kicked off the modern fight for gay and lesbian rights in the US, he displayed scant desire to demand recognition or equality for the community even though as time passed "he was living in a glass closet", according to Kopelson.

Many younger activists, fighting to challenge stereotypes about their sexual orientation, resented the way he constructed a neutered, effeminate persona designed not to frighten or challenge the mainstream, argues Pyron.

"Nothing about him speaks to a modern gay man," Pyron adds.

"He's a political conservative, he goes to the Ronald Reagan White House - he's very sympathetic to the values of mid-western America."

Despite his huge fame at the peak of his career, Liberace - unlike contemporaries like Elvis Presley or Frank Sinatra - has few dedicated followers today. In 2010 the Liberace Museum in Las Vegas closed its doors, although it is due to reopen at a new location in 2014.

Likewise, says Kopelson, some modern gay men find it difficult to relate to him - in contrast, he says, with the actor Rock Hudson, another famous closeted celebrity of the era. Hudson's image as a ruggedly masculine romantic lead was far more significant in terms of challenging stereotypes and changing attitudes, the author argues.

Still, Liberace's supporters say he can and should be remembered as a gay icon, nonetheless - not one that represents liberation, but a none-too-distant era when sexual minorities had to communicate via coded language and innuendo.

And he continues to function as a marker of the limits of the entertainment industry's tolerance.

Behind the Candelabra's director Steven Soderbergh provoked a fierce debate when he said he had to take the film to the cable station HBO because Hollywood's studios believed it was "too gay".

Mr Showmanship, it appears, is still capable of kicking up a storm at the box office.