Poems for the lost: Simon Armitage remembers WW1

5 November 2014

In a poignant journey from Northern France to the Scottish Highlands, poet SIMON ARMITAGE commemorates World War One with seven new works capturing the stories of the conflict. Sea Sketch, reprinted here, and the other poems feature in The Great War: An Elegy, a Culture Show special broadcast on 8 November. Here Armitage writes for BBC Arts about the people, places and powerful memories that inspired his verse.

Poetry could be described as the expression of the inexpressible, and has a particular talent when it comes to commemoration, remembrance and grief, those occasions when many people find themselves lost for words.

As the anniversary of World War One loomed on the horizon, I began to feel bound by duty and tradition to write poetry that would mark this most ghastly centenary, now that the conflict itself is lost to living memory.

Objects of everyday life are always more persuasive than big philosophical concepts

The so-called Great War could be said to be both the birthplace of modern battle and of modern verse. A group of extraordinary literary minds found themselves on the front line, compelled to record their experiences with unflinching honesty, and the immediate, mud-drowned, bullet-ridden verse of Siegfried Sassoon, Ivor Gurney, Wilfred Owen and Robert Graves made a deep and lasting impression on me when I first encountered it at school.

My respect for those poets and the historical and literary importance of their work meant they'd always be there in the background, but it mattered to me that I attempted something different: a full century has passed, and in any case I’m no soldier. I wanted to reflect on that catastrophic loss of life, and to think about how we commemorate the dead for the next 100 years.

I thought about the contemporary world as well. As I began to write, my next-door neighbour was beginning a tour of Afghanistan, my cousin was working his way up the ranks of the British army, and the sight of a coffin draped in the Union flag being shouldered by armed forces personnel across a military airport was a regular item on the evening news.

We determined that we’d make a film telling seven real-life stories, with seven accompanying poems – roughly one for every 100,000 British soldiers who died in the war, although we also wanted to include not just those who lost their lives but also those who worked, grieved and even survived.

Initially, I was taken with the idea of writing a series of poems inspired by objects connected to each story. The idea had a useful logic to it, and inanimate objects lend themselves naturally to storytelling and metaphor-making.

Little things also bring about concentration and focus; cigarette cases, letters requesting new socks, spent bullet cases - the objects of everyday life are always more persuasive than big philosophical concepts, reams of information or mind-numbing statistics.

But at that stage I hadn't met any of the contributors or characters in the film. In his book Pieces of Light, Charles Fernyhough notes that memories are about the past but the act of remembering must happen in the present tense.

Every time we remember, we remake and perhaps remodel our connection with the past. As I began to meet close relatives of those who had taken part in the war, I heard vivid, powerful recollections. Love for the lost remained very much alive.

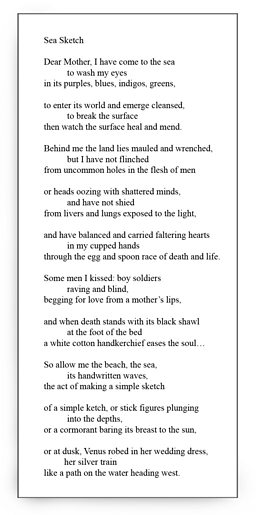

Sea Sketch

In the the small town of Etretat in Normandy, Armitage follows the story of nurse Edie Appleton through her detailed diary entries and sketches.

Her great nephew Dick Robinson reads Sea Sketch, which recalls Edie’s care of soldiers and the comforting effect of the English Channel where she swam.

Dick Robinson is the great nephew of Edie Appleton, a nurse who tended the sick and dying throughout the war. I’d read Edie’s diary, which Dick has published. It’s a moving and absorbing account of a woman doing her best to patch up thousands of men, both mentally and physically.

All the people I wrote about became as familiar and present as Edie

The diary is also full of simple, innocent sketches of Normandy sunsets, stick figures swimming in the sea and tiny illustrations of lace. Edie was no Monet, but her images and hand-written words made her real to me. Her diary was no longer just a document; it was testimony, witnessing, created by a human being trying to make sense of the madness around her.

Dick's fond recollection of his formidable great aunt, and his struggle to connect this elderly lady with the gutsy young author of the diary made things even more real. The resulting poem crystallised quickly: I tried to catch Edie’s tone of voice, and Dick read it on the beach at Etretat, Normandy – one of her favourite places during her service.

As the filming progressed so did the writing - sometimes simultaneously. The intervening century seemed to vanish, and all the people I wrote about became as familiar and present as Edie.

There was James Bennett, who tunneled out of Holzminden prison camp and whose poem was read by his daughter Laurie Vaughan; Arthur Brown, the Wolds Wagoner whose poem was read by his grandson Ted Atkinson; Amy Beechey, who lost five sons in the war, and Arthur Heath, shot in the neck on his 28th birthday.

In the end, only two of the poems were actually ‘about’ objects – one, a pressed poppy which soldier Joseph Shaddick sent home to Devon, which now lies pale and brittle in the archive of the Imperial War Museum; the other, the Clyne War Memorial, a clock tower in the Scottish Highlands, paid for by local people to commemorate local men who had given their lives.

It's a building that combines both enduring symbolism and everyday function, and at the end of the film I try to echo those themes with an edifice in words - a poem, in fact. It ends:

What better way

to monumentalise

the scattered lost

within the clockwork of the mind

than honour them

with stone and time

The Great War - An Elegy: A Culture Show Special is on BBC Two at 8pm, Saturday 8 November, as part of the BBC’s World War One centenary season.

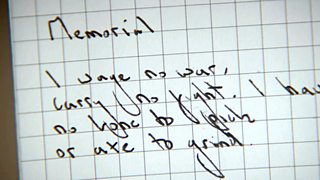

Memorial

The final destination on Armitage’s journey is the village of Brora in Sutherland in the Scottish Highlands, where he reads his poem Memorial.

The unique Clyne War Memorial is a clocktower which chimes every 15 minutes for military personnel from the area who have died in various conflicts down the years.