The big brain-maintenance experiment

One of the things that worries nearly all of us is the prospect of losing our marbles.

The brain is an amazing engine composed of millions of intertwined brain cells supplied by an intricate network of blood vessels, and over time its ability to function, as well as this blood supply network, can deteriorate. Cognitive decline was commonly assumed to be an inevitable part of the aging process, with our brains naturally changing and deteriorating slowly as the years pass. In recent years, though, a huge market has sprung up with products, games, puzzles and techniques that claim they can boost our brain power, often aimed at those who are worried about this decline.

But is there really anything we can do to keep our minds sharper as we age?

What if we could not only stop the decline, but could actually improve our brain power in older age? Recent scientific research suggests that we can do just that and with the help of experts at Newcastle University and 30 willing volunteers, Trust Me, I’m a Doctor have tested the theory out.

The experiment

We recruited 30 volunteers aged between 50 and 90 who had a number of things in common: they were all fairly sedentary, they didn’t regularly do crosswords or Sudoku, and they were not artist or painters.

We wanted to see what doing something additional or something new did to their brain power.

We tested their mental abilities at the start and end of the eight-week period, specifically some of the skills and functions that tend to get worse with age, such as memory, concentration and the ability to plan.

We also monitored their exercise levels during this time using activity watch monitors.

We then asked our volunteers all to do something extra for 3 hours every week over 8 weeks.

We wanted to test out three different protocols so we split them into three groups:

- Group 1 = Sudoku and other puzzles

- Group 2 = walking

- Group 3 = art

The tasks

Each task places different demands upon the brain.

- Physical exercise (brisk walking) raises your heart rate, increasing general blood flow to the brain.

- Brain training puzzles, crosswords and Sudoku puzzles engage parts of the brain concerned with working memory and problem solving.

- Learning a new skill, particularly one that incorporates sustained mental attention as well as some physical activity, engages more diverse areas of our brain at the same time, for long periods, as well as increasing blood flow to the brain.

The tests

The cognitive tests were designed to assess those functions that commonly get worse as we get older.

Memory Tests

- Writing down as many as can be remembered of a list of 10 spoken words. The list was repeated three times to see how much improvement there was. A final recall was done at the end of the assessment session.

- Writing down as much as can be remembered of a short story. Again a final recall was done at the end of the session.

Tests of General Mental Speed

Joining numbered circles in order, matching patterns to numbers, and repeatedly writing “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dogs” within short time limits These tests looked at general psychomotor speed.

Tests of Executive Function (Problem solving)

Joining circles with numbers and letters inside them in order while alternating letters and numbers, writing down what two items or concepts have in common, and noting the colour in which a colour word such as “blue” is written while ignoring what it says.

The results

We found that the cognitive test scores improved in all three groups. However, the clear winners were the art group, who had the highest average improvement in their scores.

Undoubtedly, learning life-drawing was a new mental challenge for our novice artists. Research suggests that the 'new' aspect of the activity is key - learning a new skill seems to be more effective than practising an existing one.

Our results also suggest a further reason for the art group's success. The data from the activity monitors showed that across all three groups, the volunteers who were the most active showed the greatest improvement in the mental tests.

Though exercise wasn't their main task, the art group's average activity levels increased. It seems that they may have benefitted from a double brain-boosting effect: from the mental challenge of learning a new skill, and from being more active physically.

The results in depth

Although in our experiment we found that the art group improved the most overall in the cognitive tests, we did find improvements in all the groups but in different ways.

The puzzle group tended to see improvements in problem solving.

The exercise group saw less variation in their improvements across the cognitive tasks. It’s thought that the increased blood flow during exercise helps to improve general brain function by maintaining a healthy supply of blood, oxygen and glucose to the brain.

Learning the skill of life art drawing was definitely a mental challenge for our volunteers, engaging different areas of the brain as well as engaging in physical activity.

What’s happening to the brain?

To try and understand what is happening in the brain we scanned the brains of three volunteers using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), one from each group.

During the scans we presented the volunteers with Sudoku puzzles or sketches of the human body and asked them to perform a simple judgement task about the puzzles or sketches. There were also periods when volunteers rested while we scanned their brains.

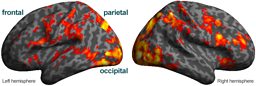

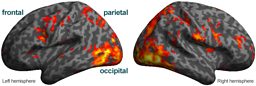

To find parts of the brain involved in these tasks, we compared periods when our volunteers were doing each task to periods when they were resting. What we found was that our tasks generally recruited large areas of frontal, parietal and occipital lobes in both hemispheres. The frontal lobe is involved in problem solving and decision making, the parietal lobe is involved in attention, and the occipital lobe is involved in processing visual shapes.

Exercise group

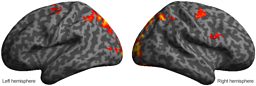

For the volunteer from the exercise group (Group 1), there was no difference in brain activity when she performed the puzzle task compared to when she performed the sketch task.

In these brain figures, the colour represents the strength of brain activity: the more yellow the colour is, the stronger the brain activity.

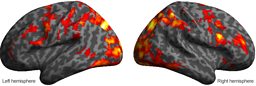

Puzzle group

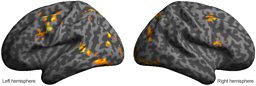

For the volunteer from the puzzle group (Group 2), the visual occipital areas were not recruited when she performed the puzzle task.

This volunteer also recruited smaller areas of brain activity for both tasks compared to the volunteer from the exercise group.

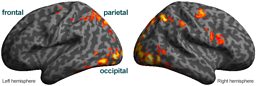

Drawing group

Finally for the volunteer from the drawing group (Group 3), there were smaller areas of brain activity when she performed the puzzle task compared to when she performed the sketch task.

Bearing in mind that we only had one volunteer from each group and that brain activity varies across individuals, we found evidence that different forms of training affected brain activity. In particular, exercise led to more overall activity in frontal, parietal and occipital lobes compared to the other forms of training. Puzzle and art training can influence this overall brain activity pattern.

The take-home message is that exercise can boost overall brain activity, and this boost can be specific to learning a new skill as we see in the volunteer from the drawing group.