From prison to the Paralympics

- Published

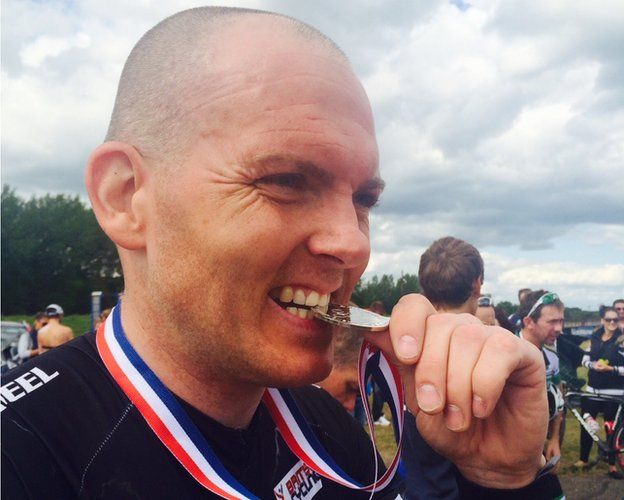

When Craig Green went to prison in 2010 he didn't envisage that five years later he would be training to become an elite cyclist, in the hopes of making the Paralympic Games in Rio.

A friend approached him seven years ago to say there was work available at a cannabis farm for him and five others, and the money would be good. Unemployed at the time, Green quickly accepted.

"I'm not criminal minded, and had never done anything like it before," he says, "but I was smoking a lot of cannabis so it felt like an ideal job."

Each day he would travel to a farm in Haddenham, Cambridgeshire, where they rented a barn the size of a football pitch, which housed marijuana plants. At the height of the operation, they were looking after a crop with an annual turnover of about £6m.

He was paid weekly, in cash left at the barn in a brown envelope.

Initially Green enjoyed the work, but began to realise it was a more organised, larger scale operation than the one he thought he'd signed up for.

He started lying to his partner, telling her he was working on building sites, and says he wasn't taking proper care of his daughter, Millie, who was a year old at the time. As time passed he began to feel uneasy about his involvement with the farm.

Career advisers at school had told Green he would never get a job in a skilled trade because his disability made that difficult, so while most of his friends were securing work as plumbers, bricklayers and carpet fitters, Green struggled to find something he found rewarding.

He has Poland syndrome which for him means he is missing two fingers on his right hand, and the ones he does have are underdeveloped. His right pectoral muscle is also missing.

"It was quite difficult growing up with a bad hand," he says. "Kids can be mean and they used to say horrible things."

When he was in primary school he was happy telling bullies to be quiet, but as he got older, and started secondary school, his natural reaction was to deal with it physically: "It probably wasn't the best way," he says, "but they didn't say anything else after that."

In the past Green tried out for the Army and the fire service, but was unsuccessful both times. "I was just much slower at the physical tests," he says, "like climbing."

After a series of heavy labour jobs in factories and on building sites, he lost motivation and felt there was nothing there for him, so when the offer to farm drugs came along, he said yes without hesitation.

In July 2010 Green was working at the barn as usual when he and his workmates heard a helicopter and cars approaching. Before they knew it, police were raiding the site and Green was arrested in a dramatic swoop. He says it happened so quickly he didn't really have time to process it, but car upon car kept arriving, and sniffer dogs were everywhere.

Due to the scale of the operation he got a four year sentence for conspiracy to cultivate a Class B drug. In total eight men were arrested and jailed in relation to the crime, which was described at the time as "one of the most sophisticated operations ever seen by officers". The men received a combined sentence of 36 years.

When he was arrested, Green says all he felt was relief. "I felt five stone lighter," he says. "The whole thing had become much bigger than I wanted it to be."

He describes his arrest as a pivotal moment, and once in HMP Peterborough says he grew up a lot. "I started visualising a future, I got myself fit in my cell, and started volunteering at the prison gym," he says.

Other prisoners would make jokes about his disability, and hurl snide comments, he says. To deal with it he decided to get as fit as possible, and prove himself in the gym. He was often top of the fitness record table the prisoners had set up.

After a year Green was allowed to volunteer outside of the prison, and he started working at the local YMCA gym. He began thinking that he could make a career out of his new found passion for fitness.

When he was released in July 2012, the first thing Green did was go to the Paralympic Games. He remembers watching the cycling, and saying to his girlfriend, "that will be me".

Shortly afterwards he attended a sporting event called Sportsfest, in Sheffield, which showcases Paralympic sports. There were people there from British Cycling who asked him to do a trial on a static bike. He had run the London marathon just six days before and had lost almost every toenail, so the trial was hard work, but he impressed the coaches.

"They basically said, 'Wow, where have you been all this time?'" he says.

Since then he has been working hard to get the times he needs to qualify for Rio, and so far it's going well. In July 2014 he went to the cycling World Cup in Spain and came 20th in the road race, out of all the top disabled riders in the world. He currently has the second best times in the country for track, road, and time trials, behind Jon Gildea, the current number one in his Paralympic classification.

Green is determined to stay focused on cycling, and he now trains six days a week, but is keeping a sensible perspective. Since leaving prison he has had a second child and says if he doesn't make Rio it's not the end of the world.

"I run a gym, I'm a partner, I'm now a dad of two - and then I'm a cyclist on top of that. I'm not a robot who rides a bike," he says.

To hear an interview with Craig Green, listen to the Ouch podcast.

Follow @BBCOuch on Twitter and on Facebook, and listen to our monthly talk show