Technology in schools: Future changes in classrooms

- Published

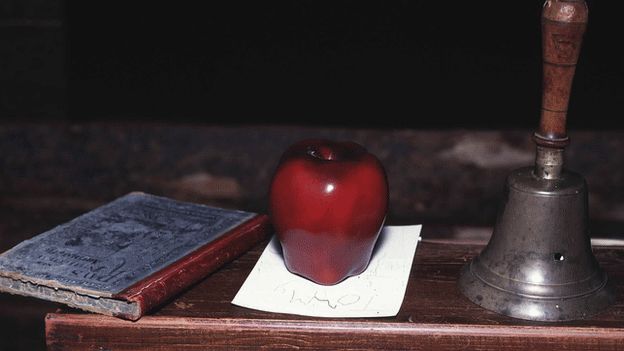

Technology has the power to transform how people learn - but walk into some classrooms and you could be forgiven for thinking you were entering a time warp.

There will probably be a whiteboard instead of the traditional blackboard, and the children may be using laptops or tablets, but plenty of textbooks, pens and photocopied sheets are still likely.

And perhaps most strikingly, all desks will face forwards, with the teacher at the front.

The curriculum and theory have changed little since Victorian times, according to the educationalist and author Marc Prensky.

"The world needs a new curriculum," he said at the recent Bett show, a conference dedicated to technology in education. "We have to rethink the 19th Century curriculum."

Most of the education products on the market are just aids to teach the existing curriculum, he says, based on the false assumption "we need to teach better what we teach today".

He feels a whole new core of subjects is needed, focusing on the skills that will equip today's learners for tomorrow's world of work. These include problem-solving, creative thinking and collaboration.

'Flipped' classrooms

One of the biggest problems with radically changing centuries-old pedagogical methods is that no generation of parents wants their children to be the guinea pigs.

Mr Prensky he thinks we have little choice, however: "We are living in an age of accelerating change. We have to experiment and figure out what works."

"We are at the ground floor of a new world full of imagination, creativity, innovation and digital wisdom. We are going to have to create the education of the future because it doesn't exist anywhere today."

He might be wrong there. Change is already afoot to disrupt the traditional classroom.

The "flipped" classroom - the idea of inverting traditional teaching methods by delivering instructions online outside of the classroom and using the time in school as the place to do homework - has gained in popularity in US schools.

The teacher's role becomes one of a guide, while students watch lectures at home at their own pace, communicating with classmates and teachers online.

Salman Khan is one of the leading advocates of "flipped" classrooms, having first posted tutorials in maths for his young cousins on YouTube in 2004.

Their huge popularity led to the creation of the not-for-profit Khan Academy, offering educational videos with complete curricula in maths and other subjects.

The project has caught the eye of the US Department of Education, which is currently running a $3m (£1.9m) trial to gauge the effectiveness of the method. Now the idea has reached the UK.

Teachers 'surprised'

Mohammed Telbany heads the IT department at Sudbury Primary School in Suffolk. He has been experimenting with the "flipped" classroom and recently expanded it to other lessons.

"The teachers facilitate, rather than standing in front of the children telling them what to do, and the children just come in and get on with what they are doing," he says.

"It has surprised the teachers that the kids can excel on their own, with minimal teaching intervention."

In the developing world where, according to some estimates, up to 57 million children are unable to attend primary school, the idea of children learning without much adult intervention is a necessity not a luxury.

Prof Sugata Mitra, from Newcastle University, has been experimenting with self-learning since his famous hole-in-the-wall computer experiments in the slums of Delhi in 1999.

He was amazed at how quickly the children learned how to use the machines with no adult supervision or advice.

From that was born the idea of "cloud grannies" - retired professionals from the UK, mentoring groups of children in India via Skype.

He won the $1m Ted prize in 2013 to build a series of self-organising learning environments in both the UK and India.

In January he completed the last of seven such units - a striking solar-powered glass building amid the lush vegetation of the village of Gocharan in West Bengal.

There will be no teachers and up to 40 children can participate when it suits them. They will have the internet at their disposal and will work in small groups. E-mediators will mentor the children via Skype.

Dr Suneeta Kulkarni, research director of the School in the Cloud project, said children would "engage in a variety of activities that are driven by their interest and curiosity", with games typically tried first.

The children will also be asked "big questions" that they can answer online.

"At yet other times these questions emerge from what the children 'wonder' about. It is also where the grannies or e-mediators are expected to play a significant role," she said.

Classroom games

When Canadian teacher and computer programmer Shawn Young wanted to spruce up his lessons, his first thought was gaming.

It was a platform many of his students were familiar with and something that was proven to engage children.

But it also had a bad reputation in teaching circles - thought to be too violent, addictive and without educational merit.

Some early attempts to integrate educational content within games failed. But what makes Classcraft different is that it is not about content - it is more a behaviour-management and motivation tool.

"The teacher teaches as normal. Teachers can offer pupils points for good behaviour, asking questions, or working well in their teams and it gives them access to real life powers," Mr Young says.

Those powers are decided by the teachers and may include handing in homework a day late.

There are also penalties for those not concentrating in class, turning up late or being disruptive.

Children play the game in teams, which means a lost point affects the entire group, and encourages them to work together.

"It is being used in a school in Texas which has a mix of white, Mexican and Afro-Americans. They would never normally speak to each other," said Mr Young.

Teachers using the system - some 100,000 have signed up since it launched in August - have noted not just better interaction between pupils, but better classroom engagement and motivation.

"As in other games there are sometimes random events, which could be something like everyone having to speak like a pirate for the day or the teacher having to sing a song in class. The kids love it."

- Published22 January 2015

- Published3 December 2014

- Published14 June 2013