How firms are fighting off spies and hackers

- Published

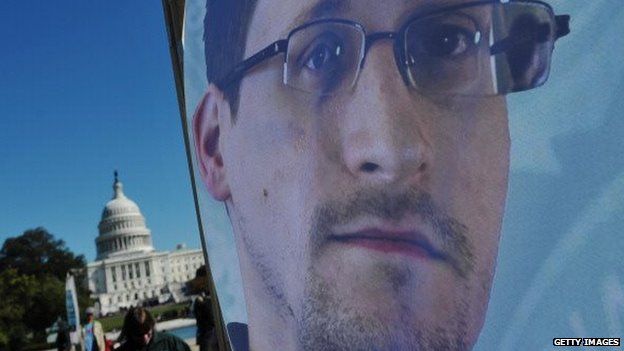

It's two years since Edward Snowden leaked details of massive covert surveillance operations conducted by the US National Security Agency and Britain's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ).

It seemed as if no-one was safe from prying eyes.

So how have businesses responded to the revelations?

And as cyber-attacks and data breaches become more commonplace - the Ashley Madison data theft being the most recent high-profile case - what are firms doing to bolster their defences against hackers?

'Nervous'

Perhaps not surprisingly, a Ponemon Institute study in April found that there has been a 34% growth in businesses using encryption methods to protect their communications.

Headlines about cyber-attacks undoubtedly drive a greater demand for privacy, says Matt Richards, vice president of products at OwnCloud, a data security company.

"It gets people nervous and a lot of folks interested in talking to us," he says.

Lawyers who trade on client confidentiality have obviously been in the front of the queue. Manhattan-based attorney Chris Gulotta says his firm has deployed DataMotion's SecureMail to encrypt all staff emails.

"I think people are getting used to interacting with secure channels now," he says.

And it's not just lawyers and big companies who've been strengthening their fortresses.

When entertainment and technology giant Sony had its emails hacked and published in 2014, embarrassing private conversations were revealed to the world.

Since Snowden...we don't have to educate the market any longer

It was this PR disaster, says William Bauer, managing director of Royce Leather, a small New Jersey retailer, that "left us wondering as a small business how vulnerable we were to succumbing to the same fate."

Mr Bauer's firm now trains all its employees to use encrypted email.

Keys to success

At least the technology is simpler to use these days.

For a long time encrypted email was a drawn-out process with users having to swap encryption keys in order to share secure messages.

"It just didn't really offer a usable solution from our perspective," says Gavin Kearney, co-founder of secure email company, Jumble. "We remove users having to create and manage any of the associated encryption keys."

Jumble's encryption process is automated - non-Jumble users are able to decrypt their received messages through the website. And as the decryption takes place within the browser, no-one else can see the contents.

"You don't need to be a mechanic to drive a car," says Mr Kearney. "Likewise, to achieve proper email security you shouldn't need to know about the ins and outs and complexities, algorithms, or managing and controlling keys."

ProtonMail, a Swiss-based encrypted email provider, has also simplified the process.

"We've switched from server-side encryption to client-side encryption," says co-founder Andy Yen. "All the encryption happens on the users' devices before the data ascends to our servers.

"We don't have a technical means to read any of our users' communications," he adds.

This makes the service popular with lawyers and doctors, as well as other clients who have to handle sensitive data.

"Also, a lot of the business community in Russia is very active on ProtonMail," says Mr Yen.

Private networks

The growth in cloud-based services, and mobile workers using their own devices, has made data security even more of a pressing issue for business.

Accessing work emails at the airport, or in a cafe over a free wi-fi service, could expose potentially sensitive corporate data to hacking.

This is where virtual private networks (VPNs) come in.

Traditionally favoured by individuals looking to hide their internet protocol (IP) addresses and keep their browsing habits secret and encrypted, VPNs are now garnering increasing interest from businesses, too, says Dan Gurghian, co-founder of Amplusnet, the parent company of Invisible Browsing VPN.

And UK-based HideMyAss says it now has dedicated teams for selling bulk accounts to businesses.

"It does good revenue," says chief operating officer Danvers Baillieu. "I can't name them, as a privacy business, but we've got big household name internet brands using our service."

VPNs are also proving popular with companies in countries where censorship is an issue, says Andre Elmoznino Laufer, head of growth for SaferVPN.

Since Snowden, VPNs have had something of an image makeover, believes Robert Knapp, boss at CyberGhost, a VPN provider.

"People are always asking why do you anonymise people, nobody has anything to hide, you just run services for the bad guys. No we don't, we run the service for the good guys," says Mr Knapp.

"Since Snowden....we don't have to educate the market any longer."

Unlocking speed

But doesn't all this encryption inevitably slow down your communications in an age where speed in business is essential?

This was initially the case for Royce Leather, says Mr Bauer - there was a slight dip in productivity as staff got to know the ropes, but "the encryption benefits were well worth the short-run sacrifices," he concludes.

The computing power behind email encryption these days means any slowdown in traffic flow to encrypt and decrypt is negligible, argues Ashish Patel, a director at Intel Security.

"If I was to send you an email that was unencrypted and send you an email that was encrypted, by the time you received and opened it, you wouldn't notice a difference," he says.

But when it comes to VPNs, Mr Laufer admits: "It will inevitably be a bit slower than without a VPN, no matter what any VPN provider claims.

"But it's a small price to pay to secure sensitive corporate data."

Of course, we may never know if all this extra focus on security has succeeded in keeping the spies at bay.

It may take another Snowden - with all the potential threats to national security that presents - to answer that billion dollar question.