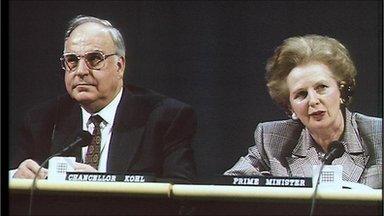

Thatcher and her tussles with Europe

- Published

Margaret Thatcher's tussles over Europe and the UK's role in what is now the European Union were among the defining moments of her premiership.

She passionately fought and won a number of battles against what she saw as the excessive powers of Brussels.

Europe also ultimately brought about Mrs Thatcher's downfall as prime minister, as her increasingly anti-EU views led the pro-Europeans in her party to move to oust her.

Yet Margaret Thatcher had not always been so vehemently opposed to European-wide initiatives.

In 1975, for instance, she played a key role in campaigning for the UK to remain in the European Community.

And in 1978 she was arguing for consideration of a common European approach to defence. She had also criticised the then Labour government for failing to sign up to the exchange-rate mechanism (ERM).

VAT battle

Once in government, however, her patience with her colleagues on the continent quickly began to fray.

In 1980, she called for the UK's contributions to the then EEC to be adjusted, warning that otherwise she would withhold VAT payments. "I want my money back!" she exclaimed.

The battle lasted four years and finally ended in victory for Thatcher but damaged relations with other EC countries.

Then came Westland - Michael Heseltine's battle to keep the helicopter company in European hands with a takeover by a European consortium.

Mrs Thatcher was insistent that the US firm Sikorsky should have it instead.

She won, he quit and the affair caused further concern among pro-European Tories.

In 1988 there came the controversial "Bruges speech".

'No. No. No.'

"We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels," Mrs Thatcher declared.

It delighted the right of her party but horrified those more well-inclined towards Europe.

All of this came against a backdrop of a government split over whether to join the ERM, which Mrs Thatcher eventually agreed to do in October 1990, little knowing that she was in the final days of her premiership.

In the same month, despite increasing divisions within her party over Europe, she came up with another soundbite.

The then president of the European Commission, Jacques Delors, had called for the European Parliament to be the democratic body of the community, the commission to be the executive and the Council of Ministers to be the senate.

"No. No. No," Thatcher famously told the Commons on 30 October 1990.

It was too much for some. Two days later, the then deputy prime minister, Geoffrey Howe, quit the government and sparked the beginning of her downfall as prime minister.

His devastating Commons speech following his resignation prompted Michael Heseltine to challenge Mrs Thatcher's leadership. Within a few weeks, she was heading out of Downing Street.

But despite all her battles over Europe, Mrs Thatcher did also sign the Single European Act, which created the single European market - one of the biggest acts of European integration.

In her 1993 book, The Downing Street Years, she defended the decision, saying: "Advantages will indeed flow from that achievement well into the future."

Major's troubles

By 2002, however, she had changed her mind, believing signing up to the single market had been a terrible error.

After being ousted from Downing Street in 1990, Mrs - later to become Baroness - Thatcher continued to make her views known.

As her successor, John Major, fought Tory rebels over the Maastricht treaty, her disdain for increasing EU integration burned as brightly as ever.

In 1995 she criticised Mr Major's government for signing the treaty and returned to the fray the following year, saying the UK might have to pull out of the EU.

Once William Hague took over the Tory reins, she eagerly embraced his anti-euro currency stance and regularly ensured she had her say at party conferences and during the 2001 general election campaign.

Later that year she made her feelings known about former chancellor Ken Clarke's bid for the Conservative leadership, saying he would lead the party to "disaster".

Super state

"He seems to view with blithe unconcern the erosion of Britain's sovereignty in Europe," she said, adding that his leadership would put Europe "at the forefront of politics".

And although illness forced Lady Thatcher to step out of the limelight, it did not stop her making her increasingly outspoken views on the EU known.

In her 2002 book, Statecraft, she suggested the European single currency was an attempt to create a "European super state" and would fail "economically, politically and socially".

She called for a "fundamental re-negotiation" of Britain's links with the EU, stopping short of calling for withdrawal but nevertheless suggesting that the UK should pull out of common agricultural, fisheries, foreign and defence policies.

"Most of the problems the world has faced have come from mainland Europe," she wrote. "And the solutions from outside it."