Knut polar bear death riddle solved

- Published

Scientists say they can now explain what happened to Knut, the famous polar bear that drowned at Berlin Zoo in 2011.

A new investigation has shown that he had a type of autoimmune inflammation of the brain that is also recognised in humans.

Researchers hope this knowledge can help both human and animal sufferers.

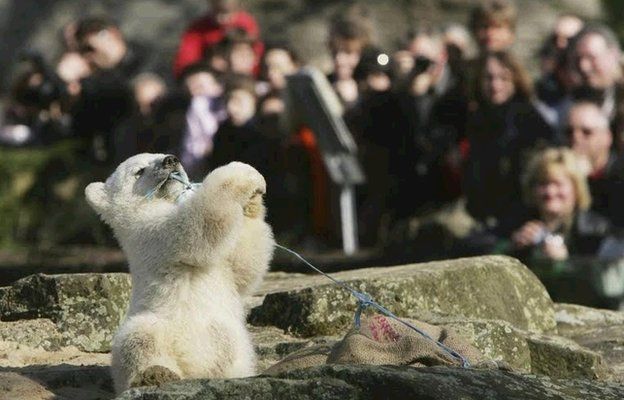

Knut became an international celebrity, after being abandoned by his mother and then hand-raised by a zookeeper.

For a while, he was the most recognisable bear on the planet, with his face featuring regularly on TV and in newspapers, and even on the front cover of an edition of Vanity Fair magazine.

His death was as public as his life. Knut experienced a seizure and collapsed into his enclosure's moat - right in front of the many zoo visitors who had come to see him - and never regained consciousness.

The necropsy established he had encephalitis, a brain inflammation, but the investigating scientists could find no reason for it.

They suspected some kind of infection, however all pathogen screening drew a blank.

It was an expert in human disorders that had the first inkling as to what the root cause might be.

Dr Harald Pruess, from the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, treats patients with a condition known as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

He recognised some commonalities in Knut's post mortem reports, and further tests on preserved brain samples from the bear confirmed the connection.

"The disease which we have now identified as the cause of death is an autoimmune inflammation of the brain," the neurologist told reporters.

"Antibodies that normally help to defend us against viruses or bacteria can obviously under certain circumstances turn against their own body and attack nerve cells.

"In the most common autoimmune encephalitis, these antibodies bind to a glutamate receptor in the brain called NMDA receptor and cause seizures, cognitive impairment, psychosis or coma."

In humans, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis affects about one in 200,000 people a year, mostly women.

It is quite often seen in patients with ovarian cancer. The same antibodies produced to fight the tumour will also attach to the brain cell receptor. An unfortunate case of "friendly fire", as Dr Pruess put it.

Knut is the first non-human subject in which anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis has been demonstrated, and in their paper, published in the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers say it is very probably far more common than previously assumed - not just in captive or domesticated animals, but also in the wild.

Prof Alex Greenwood: "The fame of Knut, we hope, will raise awareness"

In humans, the disease is treatable. Patients are given steroids and undergo what is known as plasmapheresis to remove the responsible antibodies from their blood.

Co-author Prof Alex Greenwood, from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Berlin, said similar therapy could now be developed for animals.

He told BBC News: "Pretty much every aspect of Knut's life was played out in the public sphere.

"And reflecting on it now, we're very happy to reach the point where we can end the story by saying why he died.

"There's some closure. Closure for him, but it opens up possibilities for other animals. He will be the trigger for research that may help not just other polar bears but other wild and captured animals as well."

And both Prof Greenwood and Dr Pruess said they hoped the publicity surrounding Knut would raise awareness of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in the medical profession, ensuring human patients were diagnosed and treated promptly.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published22 March 2011

- Published19 March 2011