The digital game that could cure TB

- Published

A unique collaboration between two Scottish universities has produced a digital game that fights tuberculosis.

A team of undergraduates from Abertay University in Dundee has created Sanitarium, a game that invites people to play doctor.

Using scarce resources they must treat as many TB patients as they can.

Behind the game lies a mathematical model developed at St Andrews University that uses data from human interactions to simulate a drug trial.

The data collected by the game could help deliver new drug treatments to the developing world quicker and cheaper than ever before.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global killer that is increasingly resistant to antibiotics. The global TB Alliance has been formed to fight it.

Prof Stephen Gillespie, who holds the Sir James Black chair of medicine at St Andrews University, is part of that fight.

"For a lot of the poorer parts of the world it remains a common problem," he says.

"There are about eight million new cases ever year and about two to three million deaths."

Innovative approaches are called for. Which is why Professor Gillespie found himself issuing a brief to a group of third year computer game students at Abertay.

They call themselves Radication Games.

Their task: to develop a game about curing TB in a virtual world that could lead to the same thing happening in the real one.

Their first hurdle: to make a game people would actually want to play.

The team's lead programmer James Warburton led me through it.

"The player is presented with a doctor screen - the doctor they'll be playing," he said.

"It gives them information about how many patients they've got to cure and how many patients are still in treatment.

"On the next screen they get presented with a world map which represents patients as red dots across the world.

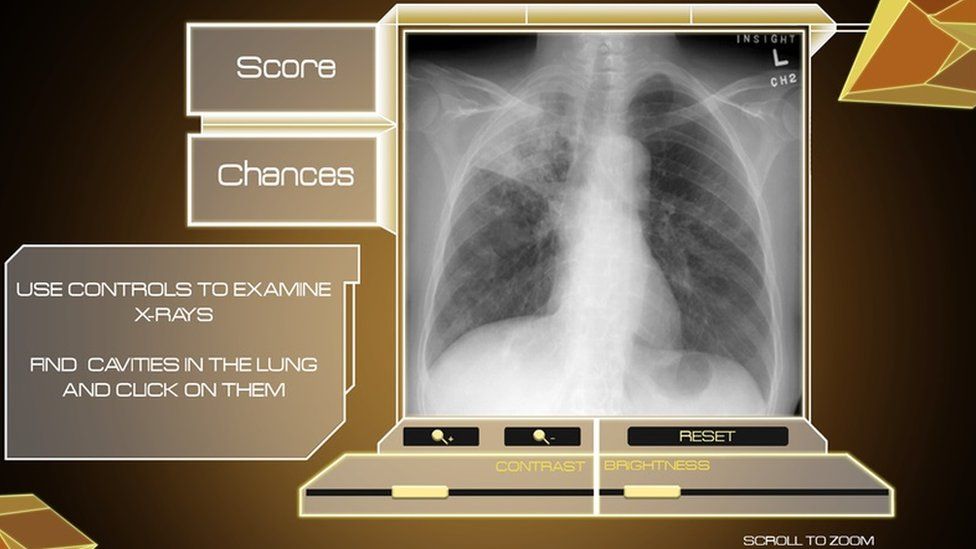

"They're given three mini-games which diagnose and treat the patient."

New drugs

For lead artist Chris Box the task was to make the game attractive.

He says: "The medical world is quite a dry subject, so we wanted to make it kind of pop and interesting so that people would want to pick it up and grab it.

"That's been the challenge."

And has he risen to it?

He smiles: "I hope so. It's been received well."

For a typical third year student project, creating an engaging digital experience would be enough.

But Prof Gillespie wanted more than a game.

He says: "We're in the fortunate situation now that we're starting to see new drugs coming through for tuberculosis.

"But each clinical trial costs more than $50m and there may be 100 different combinations.

"We can't afford to do that many clinical trials.

"So if we can have a virtual clinical trial that tests the hypothesis whether that will work, we can select a smaller number of studies that are really worth doing and worth investing in."

That is why, behind the game, there lies a mathematical model.

It has been developed at St Andrews to simulate drug trials, to cut the cost and length of the real things.

Mathematical model

At Abertay the Sanitarium team, led by game producer John Brengman, took on the task of building a game around that life or death research.

"With the mathematical model we have analytics running in the background that basically takes all the information happening in the game," he told me.

"And we can save that and segment that and give it to the scientists and doctors to look at later.

"But if they were to come up with a new treatment for tuberculosis and a new mathematical model, we could plug that into the game.

"We could get players around the world playing it. And then we could take that new dataset, compare it to the old dataset, and there you have a simulated drug trial."

That's because the people who play the game add a vital element to the theoretical model: themselves.

"The most difficult thing in a mathematical model is human behaviour," Professor Gillespie says.

"We can use the people who're playing the game to mimic that behaviour."

Job satisfaction

For the team's sound designer Mazen Magzoub project Sanitarium has a special resonance. He's from Sudan.

"There isn't enough medication," he says.

"And even when there is enough medication the nature of living in Sudan does not allow the patient to continue (treatment) for the prescribed period.

"And that makes the tuberculosis bacteria tolerant towards that certain type of antibiotic.

"That's basically the challenge in the developing world."

The Radication Games team intend to stay together after they graduate to continue developing a project which brings with it a special kind of job satisfaction.

The success of most digital games is measured in money. For Sanitarium it'll be in how many lives it saves.

And for Prof Gillespie, working with the games team has brought another more personal benefit.

He says: "They're very, very talented in every respect as you can see from the game.

"Even more talented: they make my research seem cool."