The tale of the dog behind the 'kiss of life' discovery

- Published

There are about 30,000 cardiac arrests every year in the UK and ten times that number in the US. It is one of the most common ways to die.

It is also one of the most common scenarios in which a bystander can save a life through CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the technique used to keep blood and oxygen pumping round the body until emergency help arrives.

This 'kiss of life' has an intriguing history stretching back over 100 years to when electricity was first being installed in domestic homes and, in part, it owes its discovery to the fate of an unnamed lab dog.

Throughout the early 1900s an electrical revolution hit America, and homes became populated with electrical appliances - everything from light bulbs to refrigerators.

But, on the down side, electrocution was a major risk to people working on the newly-installed power lines. Many died of cardiac arrests.

Shock tactics

As a result, external defibrillators had been invented to shock the heart back into rhythm without opening the chest - but they were too big and cumbersome to use outside of hospitals.

In the 1950s, the Edison Electric Institute in the US decided to sponsor researchers to investigate the effects of electrical currents on the heart.

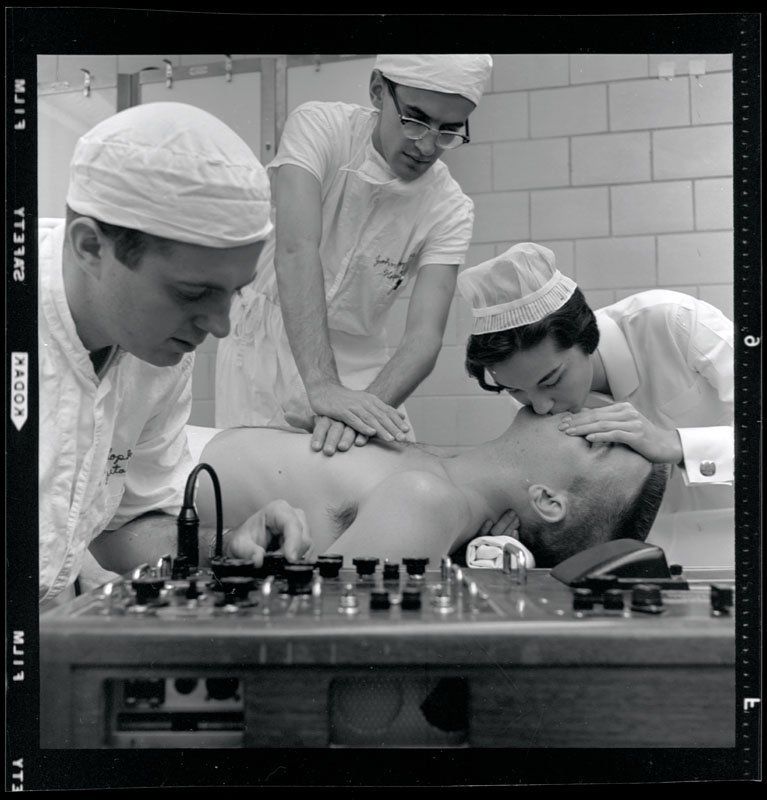

Enter Guy Knickerbocker, a fastidious, 29-year-old graduate working under electrical engineer William Kouwenhoven in one of the labs at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland. They were trying to improve the external defibrillator, which Kouwenhoven had invented a few years earlier.

In 1958, before the ethical treatment of animals became a serious consideration, their experiments involved testing on laboratory dogs.

Knickerbocker, now 82 years old, remembers working with a colleague one day when, suddenly, one of the dogs went into cardiac arrest, or ventricular fibrillation (VF).

Normally when this happened, they would use a defibrillator to shock the dog's heart back into rhythm - but that day they were in the lab on the 12th floor and the equipment was on the fifth floor.

The notoriously slow lifts in the building meant they would never get the defibrillator to the dog in time.

"There is very little chance of survival after cardiac arrest that goes on longer than five minutes," says Knickerbocker.

'Sprang to life'

Knickerbocker had a brainwave. Only a few weeks earlier he had observed that just the pressure of the defibrillator paddles on the dog's chest caused a change in blood pressure.

Did this change in pressure mean that the blood was moving around the body?

He took a chance: "We started to pump the dog's chest because it seemed to be the right thing to do."

Knickerbocker raced along the stairs to the fifth floor to get the defibrillator while his colleagues pressed the dog's chest for 20 minutes - four times longer than any previous successful attempt.

When he arrived back with the defibrillator and administered two shocks, the dog sprang back to life.

The importance of their discovery cannot be overstated; the experiment established beyond doubt that rhythmic pressing of the chest could sustain life.

Knickerbocker says: "We had found a way to slow down the dying process, and give people time to receive defibrillation".

From pooch to people

Knickerbocker excitedly shared his discovery with cardiac surgeon, Dr Jim Jude, who worked in the next-door lab.

Dr Jude immediately realised its potential, and along with Kouwenhoven, set about working out exactly where to push, how often, and how much force to apply - and found they could extend a dog's life for more than an hour.

"I didn't believe the chest compression technique would ever translate to humans, and neither did a lot of my colleagues," he says today.

This included the head of surgery at Johns Hopkins at that time who wanted the team to provide a lot of evidence before he let them publish their findings.

However Dr Jude was convinced the dog-saving technique could work on people.

The chest compression technique, he realised, could be used to simulate up to 40% of normal cardiac activity. The only problem was that there was no-one to test it on.

A little over a year later, a 35-year-old woman, who was admitted for a gall bladder operation at Johns Hopkins, reacted badly to the anaesthetic and went into cardiac arrest.

Dr Jude immediately began applying rhythmic, manual pressure to her chest. Within two minutes her heart started again and she went on to have the operation and make a full recovery.

'Happy and proud'

This led Kouwenhoven, Jude and Knickerbocker to publish their discovery in a paper in 1960.

"Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures," the authors concluded. "All that is needed are two hands."

In collaboration with another research group who were looking at ventilation techniques, they developed modern CPR.

Now it is taught across the world and in some countries it is also taught in schools.

The American Heart Association estimates that CPR provided immediately after sudden cardiac arrest can double or triple a victim's chance of survival.

How to save someone's life with CPR

Using chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is the best way to increase someone's chances of survival, but hands-only CPR is always a good option on its own.

- Place the heel of your hand on the breastbone at the centre of the person's chest. Place your other hand on top of your first hand and interlock your fingers.

- Position yourself with your shoulders above your hands.

- Using your body weight (not just your arms), press straight down by 5-6 cm on their chest, then repeat until an ambulance arrives.

- Try to perform 100-120 chest compressions a minute.

Useful links

Knickerbocker is philosophical about their achievement. "After everything died down, I never dwelled on our work in the lab that often. But I was happy and proud that it had worked out so well."

"Then, recently, I saw some statistics on the internet, counting up the number of people successfully resuscitated using CPR. It was over five million. I was astounded, of course."

He adds wryly, "This doesn't take into account numerous pets around the country that have also benefited from chest compressions. But it's still a lot."