How firms can avoid being boxed in

- Published

Once upon a time I had an editor who was paralysed by the word "innovation".

"People don't understand what it means," he opined. "Don't use it."

It was an edict that made the job of making programmes about business rather difficult.

Because the era of doing things in the same way decade after decade is over. Organisations are confronted by external change and the urgent need to change themselves. Innovation is nothing less than a matter of corporate survival.

Well that particular editor is no longer in charge, so now I'm free to talk about inn-o-vation. Along with many other people. The need to innovate has become a commonplace corporate preoccupation. But acknowledging its importance does not make it any easier.

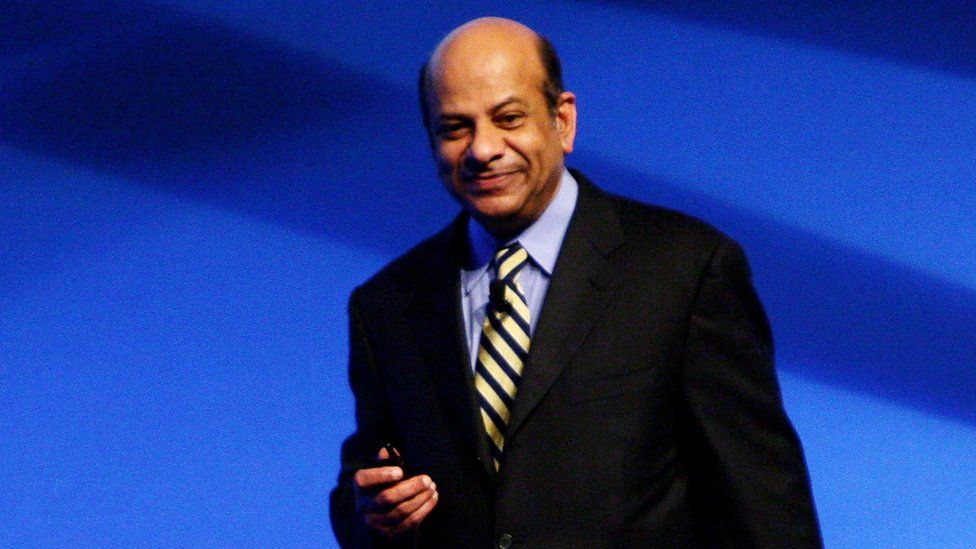

So here with a bit of help is Vijay Govindarajan. He's a long-standing professor at the oldest management school, the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth in Massachusetts. He has also been chief innovation consultant for General Electric.

And his new book The Three Box Solution, has some noteworthy insights into the innovation process.

First a word about Prof Govindarajan. He was born in India in a village not so far from what was then Madras, now Chennai, in the south. As a boy, he was much influenced by his grandfather Tagore Thatha, whose picture is part of this book's dedication.

You won't have heard of his grandfather - he stayed at home reading. He revered knowledge above everything else, including work.

'Future is now'

Impelled by his grandfather's example, Prof Govindarajan flung himself into studying, first in India, then at Harvard University in the US. He told me once how clearly he remembers one particular incident that happened when he had recently qualified as an accountant.

In 1977 there was national uproar when Coca-Cola was flung out of India by a government that demanded it shared its technology secrets with local partners. The company refused to share its recipe with anyone.

This made a huge impression on him. When he started studying and then working in the US, he saw Western or international values through the prism of his Indian experience.

This perspective is a valuable one. Familiar ideas taken for granted by Western managers look slightly different from the viewpoint of the Indian management thinkers who are now in prominent places in academic life.

It is a perspective that Prof Govindarajan specialises in. In an earlier book, Reverse Innovation, he writes about innovations and products that are originated in the developing world, not adapted from those created for the rich world. This is very different from the way a multinational company traditionally thinks about rolling out new products - at home first, everywhere else later.

This latest book is also about innovation, and it is also rooted in that Indian perspective. The Hindu philosophy of creation, destruction and preservation is the basis of The Three Box Solution. In Hinduism it is a continuous cycle without beginning or end.

If that sounds intimidating, it isn't. By creating three boxes that a company ought to concentrate on when it is trying to pilot its way into the future, Prof Govindarajan may enable its leaders and workers to think outside the box their normal experience traps them in.

Prof Govindarajan's box one is "managing the present", while box two is "selectively forgetting the past", and box three is "creating the future".

Prof Govindarajan says the difficulty for any business is balancing two things very much at odds with each other in most organisations - running at current peak efficiency (box one), while at the same time inventing a new business model (box three).

Box three sets aside many (if not all) of the practices and principles which have built the company and made it successful. It needs very different skills, practices and leadership from up to now. Balancing the boxes is very difficult.

But it is the second box that's particularly interesting, and particularly hard for most organisations to use. While keeping the current business going (it's making the money, after all), an innovative company has to simultaneously forget what made the business successful in the past.

All sorts of thing may need to be forgotten, says the professor. The fact that the company makes products, for example. That it uses dealers with physical premises to distribute its products. That it is based in a particular city, or country. That it knows who its customers are.

These assumptions are not just part of management strategy, the reason why the company has been successful up to now. They are deeply embedded in the corporate structure - company divisions, who reports to whom, what can be outsourced... and what are the corporate crown jewels.

These considerations are what insiders think of as corporate culture. But they may be a very serious inhibition to real innovation.

'Future weaknesses'

Prof Govindarajan says there is nothing quite as powerful as an entrenched set of obsolete values and practices, freezing time and enforcing inertia. Box two is about forgetting them, in order to innovate in a way very detached from what has gone before.

Of all the ideas and examples in this book, it is the need to forget the (successful) corporate past that is the most striking, and perhaps the most counter-intuitive.

You might say that success is the forerunner of company failure. Prof Govindarajan says: "Future weaknesses are embedded in current strengths."

Or to go further, in a world as disruptive as the one we now live in, really big corporate success is a creator of failure to come.

Success anesthetises an organisation from what is going on in the world it operates in.

To create the future, a company has to forget the past - while at the same time using the revved up revenue flows from present operations to finance that ever-necessary change. An unceasing corporate tug-of-war.

No wonder my editor could not understand inn-o-vation.