The Draw of War: Walt Disney and World War Two

To mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, Donald Duck Gets Drafted sees acclaimed political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe explore Disney’s fascinating contribution to the war effort – which reportedly landed Walt a place on Hitler’s personal hit list. The programme’s producer Kellie Redmond reflects on this little known part of wartime history…

In December 1941, Time magazine was about to print its end of year issue, its front cover carrying a big picture of Dumbo - that loveable elephant with the gigantic ears who had helped The Walt Disney Studio achieve soaring box office figures that year.

But on 7 December, Japanese aircraft attacked Pearl Harbour, abruptly bringing America into World War Two – and ousting Walt’s latest creation from the front page.

Yet, if the war led to a dip in Disney’s fortunes, it was only a temporary one.

Within just six months, The Walt Disney Studio in Burbank, California, was declared a war plant. Its filmmaking capacity was given over to the Allied effort and its well-loved cartoon characters all enlisted to do their bit for their country - from Donald Duck and Pluto to Mickey Mouse, Snow White and beyond.

Through a mix of groundbreaking military training films, features and propaganda shorts, as well as insignia, books, posters, and much more, Disney sought to boost troops’ morale on the frontline and promote government policies on the home front.

As someone fascinated with animation history (my last BBC Radio 4 documentary was about Cosgrove Hall, the iconic British animation house behind Danger Mouse and Jamie and The Magic Torch and more), I was surprised just how little known Disney’s wartime role is within popular culture today. So with the BBC marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, it was a side to the war that I felt was more than worthy of shining a light on.

If the war led to a dip in Disney’s fortunes, it was only a temporary one.

And who better to present Donald Duck Gets Drafted than acclaimed cartoonist Gerald Scarfe? Known for his political drawings (as well as his iconic images for Pink Floyd’s The Wall), Gerald was himself inspired to become an artist after seeing Pinocchio at the cinema as a child, and went on to be production designer on Disney’s 1997 big screen animation Hercules.

Having grown up during the war too, in the programme Gerald is also able to provide a vivid personal account of one of the more shocking wartime pieces that featured a Disney character. It was an item that was intended to calm children during The Blitz and which I won’t spoil by revealing here. Listen to the programme to discover just what it was.

Meanwhile, the military training films that The Walt Disney Studio produced were not just technically innovative. The films were strategically important too. For the first time, animation was effectively used to help large numbers of troops visualise combat situations before reaching the battlefront.

Disney never referred to such films as ‘propaganda’ but officially re-named them ‘psychological productions’.

America’s entry into the war also revealed its true potential on the Home Front: as a propaganda machine. Although - concerned as ever with the wholesomeness of its image – Disney never referred to such films as ‘propaganda’ but officially re-named them ‘psychological productions’. This included several humorous anti-Nazi shorts including Der Fuehrer’s Face, which went on to win an Oscar.

However, there were no gags in the 1943 propaganda short that followed – Education for Death – adapted from a book of the same name by Gregor Ziemer. It is a powerful film that shows the indoctrination of a little German boy named Hans, from his birth to his death. It is a far cry from the classic films featuring cute talking animals and spirited princesses that we tend to associate Disney with nowadays, and may prove something of a shock to fans of the Studio’s well-honed feel-good films.

Another recognised side of Disney’s empire today is of course the merchandise that accompanies each of its movies, and is something Gerald Scarfe recalls being part of the early design stages during the making of Hercules. The power of Disney’s characters to exist off-screen in this way was already in full-effect back in the 1940s when Walt threw his weight behind the war. But this took on a very different role during wartime in the shape of the military insignia that the Studios provided - completely free of charge - to any troops who requested them. Much-loved Disney characters were re-drawn to include military paraphernalia, which members of the Allied forces would then put on the side of their vehicles, uniforms and more.

It is hard for us to comprehend today just what it meant to those fighting on the frontline to have an insignia designed especially for them by Disney or, indeed, for movie-goers getting tickets to see Donald Duck and friends advocating government policies on the big screen. But many Americans had shared their childhood with Walt, growing up on his cartoons and been a part of the 1930s Mickey Mouse Club – which was something of a cultural phenomenon and at the time had even more members in The States than the popular boy scouts and girl scouts movement combined.

In the programme, we also explore why it was Donald Duck rather than Mickey Mouse who became The Studio’s wartime mascot, as well as Walt’s own personal role as a Goodwill Ambassador in South America, intended to help stem potential Nazi influence across the continent.

But what motivated Walt to use his inkwells as weapons of war in the first place: was it pure patriotism or just a shrewd business move? Before the war, Disney distributed its films to around 55 countries. By 1944, 81% of box office revenue is said to have been generated by just three: the US, Canada and the UK. So it’s clear the Studios needed to find alternative ways to keep afloat to survive.

Yet, Disney made a lot of the wartime animations for the government and military at cost, even bankrolling the air strategy film Victory Through Airpower himself, not to mention the insignia his Studios created for troops entirely for free. In Donald Duck Gets Drafted we look at whether a certain personal incident in his youth led to a deep-seated patriotism that potentially over-rode commercial interests.

And, of course, the programme reveals that film which reportedly put Walt on Hitler’s own personal hit list. A clue: it involves raspberry noises and an unflattering Adolf animation.

Listen to Donald Duck Gets Drafted, part of the pan-BBC programming marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two.

-

![]()

The strange true story behind The Da Vinci Code

How a fraud started a conspiracy theory that captivated the world.

-

![]()

Six things you need to know about deepfakes

The risks deepfakes pose to democracy, and their potential in health care.

-

![]()

Nazanin and the mystery of a decades old tank debt

Has an old tank debt with Iran cost Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe her freedom?

-

![]()

The incredible rise and remarkable fall of plastic

The extraordinary story of how plastic became a major player before its fall from favour

-

![]()

Was this the hack that changed the world?

Who was behind the 2009 hack of climate change emails from the University of East Anglia?

-

![]()

Poison – the mystery of South Africa’s toxic new political conspiracy

Who is poisoning South Africa's politicians?

-

![]()

How do we send a message to the far future?

How do we warn our distant descendants of dangerous nuclear waste buried deep underground?

-

![]()

A secret history of hi-vis

The bright jacket has a chequered past of sociological implications. No, honestly, it has!

-

![]()

Do our cats judge us?

Comedian and cat owner Suzi Ruffell investigates the behaviour of our feline friends.

-

![]()

Does time move faster as we get older?

What are the emotional, physical and cultural factors which affect our perception of time?

-

![]()

Six of the most mysterious masked musicians

From Daft Punk to Sia, we rundown the finest mask-wielding artists.

-

![]()

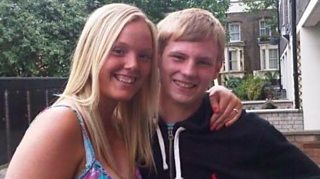

The tragic death that brought a community together

Exploring the emotional impact of the killing of Russell “Barty” Brown.

-

![]()

Listen to these five inspirational documentaries

Five incredible stories told in captivating ways.

-

![]()

The reality of conversion therapy

Caitlin Benedict explores the practice of conversion therapy.

-

![]()

Sensory overload: My life as an autistic mother

For autistic people, sound and touch can cause sensory overload. What if you're pregnant?

-

![]()

Is it still OK to read Harry Potter?

Can we enjoy a book if we don't agree with the author?

-

![]()

Playing video games with the dead

The unique ways gamers have dealt with losing someone.

-

![]()

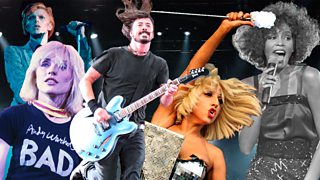

Will live music ever be the same again?

Arlo Parks speaks to musicians about the impact of the pandemic.

-

![]()

Double murder? The case that divided South Africa

Two dead men. A dozen suspects. Blood Lands is a true story told in five parts.

-

![]()

Lift off! 10 incredible facts about the elevator

The lift's invention changed the way we live in more ways than you can imagine.

-

![]()

Five remarkable works of art made out of pollution

From beautiful toxic sludge paintings to meringues that harvest polluted air.

-

![]()

Eight tips for how to disagree better

Can you disagree with someone without falling out?

-

![]()

Nine fascinating facts about the history of exhaustion

Are we really more exhausted today than we have ever been before?

-

![]()

If you were given free money to spend – what would you buy?

The sometimes surprising ways East Germans spent 'Begrüßungsgeld' windfall from the west.

-

![]()

The Hidden Story of British Slavery

The alarming truth about slavery in modern Britain.

-

![]()

11 niche jobs that actually exist

Bizarrely specific jobs that are somehow real

-

![]()

At what age should someone be allowed to marry?

How young is too young to get married?

-

![]()

Why is music getting weirder?

The radical music being made in the margins of Britain.

-

![]()

Are video games art? Eight reasons to say yes...

Video game evolution: telling stories and stirring emotions in a uniquely interactive way.

-

![]()

Meet the most powerful man you’ve never heard of

The man who made the post-truth world

-

![]()

What happens when neighbours become family?

The heart warming story of how two very different families came together to raise a baby.

-

![]()

Five incredible underwater artists

Art that'll make you hold your breath.

-

![]()

The New Age of Consent, by Jameela Jamil

Jameela explains why her revelatory journey through sexual politics is a "must listen".

-

![]()

The Pop Star Philosophy Quiz

Can you pin the quote to the philosophical pop star?

-

![]()

Seven things you might not know about stripes

What makes the stripe such a powerful pattern?

-

![]()

Seven quirky documentaries to make boring journeys go faster

Featuring salamanders that can regrow limbs, cyborgs, and pigeon whistles.

-

![]()

Seven of the most mysterious musicians

Enigmatic performers who shunned the spotlight.

-

![]()

Seven times sport became political

Black Power salutes, angry farmers and Pussy Riot

-

![]()

Five incredible examples of slow art

Illuminated snails dancing, sculpted ash trees and music playing for 1000 years.

-

![]()

The Ultimate Rock Journalism Quiz

Link the pithy remark to the artist and be the maestro of the music journo quiz.

-

![]()

The Ultimate Beauty Quiz

Do you know your dermabrasion from your exfoliation? Take this beautiful quiz to find out.

-

![]()

How colourism complicates the dating game

Bridgitte Tetteh writes about an issue affecting single black women.

-

![]()

What does virtual reality look like?

View amazing images of VR worlds.

-

![]()

The man who buries planes

Artist Roger Hiorns has always been fascinated by the idea of burying planes.

-

![]()

Why I decided to get to know the man I killed

Jonathan Izard explains how a car accident on New Year's Eve changed his life.

-

![]()

Seven works of art created in Guantanamo

View pieces created in the American military detention centre.

-

![]()

Seven seriously amazing coincidences

These amazing coincidences were shared by our social media followers.

-

![]()

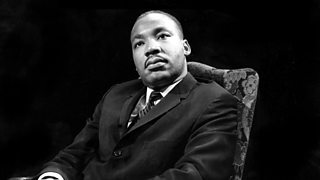

The Martin Luther King Jr Quiz

How much do you know about the US civil rights hero?

-

![]()

Seven reasons it’s great to be bald

It's time to shed the stigma about being bald.

-

![]()

Are we near a cure for cancer?

Rhianna Dhillon recommends a podcast that may point the way to a cure for a form of the disease.

-

![]()

The Pankhurst Quiz

Think you know your Suffragettes from your Suffragists? Take this quiz to find out!

-

![]()

Five women who broke the glass ceiling

These remarkable women have made a real an impact on democracy in their countries.

-

![]()

The Frankenstein Quiz

Is your Frankenstein knowledge “Alive!” or in need of a jolt?

-

![]()

Why is country music a hit in Nigeria?

Tayo Popoola travels to West Africa to find out.

-

![]()

Seven things you need to know about Antifa

What is the leftist movement that has been making headlines?

-

![]()

A plate of Peru

Try Martin Morales puka picante vegetariano recipe.

-

![]()

10 Jokes That Make Russians Laugh

Viv Groskop gathers some of the best Soviet satire and proletariat punchlines.

-

![]()

Could You Be a Superstar Wrestler?

Take our quiz to see if you have what it takes to rule the ring.

-

![]()

Five Things I Learnt from Wearing a Wig

What Brian Kernohan learnt about himself and our relationship to wigs.

-

![]()

Why are acid attacks on the rise?

Ayshea Buksh investigates the rise in UK attacks.

-

![]()

Five slogans to live your life by

Could we really live by our lives by the words of a slogan? Possibly not...

-

![]()

Ten words that prove you aren't posh

Etiquette expert William Hanson explains what U and no-U now.

-

![]()

Are you beach pod ready?

Five podcasts to take on your holidays.

-

![]()

Why Ian McMillan loves being early

The poet and broadcaster ponders his need to make the clock bend to his will.

-

![]()

Fake wine – honestly, it’s a thing.

A guide to who counterfeits wine and how the Wine Detectives catch them.

-

![]()

Five Steps to the Creative World of Cosplay

A quick guide to cosplay for the uninitiated.

-

![]()

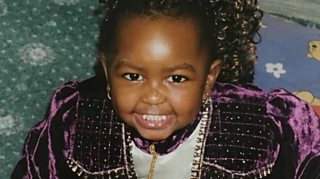

The death and rebirth of Zora Neale Hurston

Once forgotten, the author is now revered by Alice Walker and Solange Knowles.

-

![]()

Seven of literature's lustiest lovers

From Tom Jones to Adrian Mole, have a look at lust in literature.

-

![]()

Meet the Cyborgs

Five people who have modified their bodies with technology.

-

![]()

Kevin Bacon is no friend to fame

The Hollywood star has experienced the highs and lows of what fame has to offer.

-

![]()

Paul Mason investigates social media marketing

The journalist looks into a new strain of viral advertising.

-

![]()

Miles Jupp asks if a woman invented James Bond...

Phyllis Bottome is little known today, but did she inspire Ian Fleming?

-

![]()

Five ways to burst your social media bubble

DJ and presenter Bobby Friction on how to escape the online echo chamber.

-

![]()

The Story of The Green Book by Alvin Hall

A travel guide like no other, for black motorists in the mid-20th Century it was a catalogue of refuge.

-

![]()

GCHQ Puzzle Book

Can you crack GCHQ's code-breaker challenge?

-

![]()

The Green Book - A Visual Journey

A visual journey into the heart of racism in the American deep south.

-

![]()

Apathy in the UK by Phill Jupitus

The comedian and broadcaster on boredom.

-

![]()

What's Rhianna Dhillon been listening to?

Meet the new presenter of Seriously...

-

![]()

What is a 'curvalicious' body?

Bridgitte Tetteh explores attitudes to female bodies in the black community.

-

![]()

The Viz Quiz!!!

It's a quiz about Viz. Pretty much the biz, is this.

-

![]()

You May Now Turn Over Your Papers

If we catch you cheating you will be escorted out of the internet.

-

![]()

Dave Pearce's top 10 Chicago house tracks

The legendary DJ picks the genre's 10 essential tracks.

-

![]()

Sitting for David Hockney

Art critic Martin Gayford learns what it's like to be painted by a modern master.

-

![]()

The Welsh Football Quiz

Test your knowledge of Welsh football.

-

![]()

Why having a baby needn’t subdue your inner geek

Five tips from Isy Suttie.

-

![]()

Mary Anne Hobbs recommends

The 6 Music DJ picks 10 great Radio 4 music documentaries.

-

![]()

Miles Davis on canvas

The legendary trumpeter's second life as a painter.

-

![]()

Ey Up! It's The Sex Pistols

The Sex Pistols visited Yorkshire twice, but what impression did they leave?

-

![]()

QUIZ: The Beach Boys or Bob Dylan?

Pet Sounds and Blonde on Blonde were both released on 16 May 1966, but which do these lyrics come from?

-

![]()

William Shakespeare's America

Robert McCrum traces the Bard's influence in the USA.

-

![]()

Three-Sided Football, A Sport for Anarchist

Ian McMillan watches from the side lines in South London

-

![]()

Why Do Dancers Die Twice?

Should professional dancers careers have to be so brief?

-

![]()

Seven Lyrics to Use in Conversation Today

These song lines have become common parlance.

-

![]()

Five Women Who Wrote Rock

These writers helped define rock journalism in the 1960s.

-

![]()

Is Mindfulness Meditation Dangerous?

Jolyon Jenkins investigates whether meditation can do you more harm than good.

-

![]()

Fake It 'Til You Make It

Why have fakes and fantasists always fascinated us?

-

![]()

Neil Innes on the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band

The band member recalls the anarchistic joy of a truly unique group.

-

![]()

Mary Beard vs Hair Dye

The writer and academic has a consultation with a legendary hair colourist.

-

![]()

The Recovering Addicts who Inspired Trainspotting

The team of recovering addicts who made their mark on cinematic history.

-

![]()

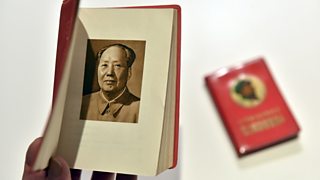

Mao's Little Red Book goes West

David Aaronovitch on how an Eastern political tract became a Western icon.

-

![]()

David Bowie in his Own Words

David Bowie's interviews reveal his humour, passion and determination to succeed.

-

![]()

Dotun and Dean

Broadcaster Dotun Adebayo revisits his youthful obsession with James Dean.

-

![]()

Gavin Esler on The Good Goering

Did Nazi leader Hermann Goering have a brother who saved innocent lives from the Holocaust?

-

![]()

10 Women Who Changed Sci-Fi

A selection of great female authors who have radically altered the genre.

-

![]()

Pick-Your-Own Utopia

Dream away those mid-winter blues by pondering our selection of fantasy idylls.

-

![]()

Meet the Burlesque Legends

Mat Fraser meets the former striptease stars back on the stage in their 70s and 80s.

-

![]()

Piers Plowright's Picks

The legendary radio maker recommends seven great documentaries for Seriously...

-

![]()

Neil Gaiman's Orphee

A poetic retelling of the Orpheus myth, from the celebrated writer Neil Gaiman.

-

![]()

Meeting Music's Nostradamus

An aspiring singer-songwriter meets the man who predicted the demise of the music industry decades ago.

-

![]()

The Seriously Hard Quiz

What have you learned from our documentaries? Try our fiendishly difficult quiz...

-

![]()

The Draw of War: Walt Disney and World War Two

Kellie Redmond explores Disney's fascinating contribution to the war effort.

-

![]()

Harry Shearer on New Orleans

The Simpsons star, satirist and actor reflects on the flood that devastated his home town of New Orleans.

-

![]()

The Bletchley Girls: Cracking Women

Meet five codebreaking women who helped beat the Nazis and are still alive to tell their tales.

-

![]()

Why We’re Hung Up on the Hang

Seven reasons to love the modern melodic drum that creates a haunting tone.

-

![]()

Philip Hoare: CSI Whale

The award-winning writer on porpoise dissections, stranded whales and beached dolphins.

-

![]()

Welcome to Seriously...

Learn more about the website and podcast for Radio 4 documentaries.