Shakespeare's Shylock: Victim or scoundrel?

8 February 2016

Man Booker winner HOWARD JACOBSON's latest novel, Shylock Is My Name, is inspired by Shakespeare's most performed play, The Merchant of Venice. Jacobson tells us why, for him, the character is a uniquely potent presence with great relevance today.

2016 sees both the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death and the 500th anniversary of the founding of the Venice ghetto.

This is an especially happy confluence of anniversaries for me in that I have just finished a novel, Shylock Is My Name, that takes its inspiration from The Merchant of Venice - and though there is no mention of the ghetto in Shakespeare's play, it is somehow impossible not to associate it with Shylock.

Isn't Shylock the most repulsive Jew ever penned, a byword for cruelty, malice and greed?

Indeed, the Venice Centre for International Jewish Studies is hoping to mark the ghetto's birthday next summer with the first ever English-speaking production of The Merchant of Venice in its main square.

There will be some who raise their eyebrows at this.

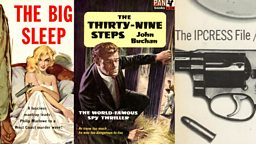

Isn't The Merchant of Venice a Jew-hating work, if not anti-Semitic in intention then certainly anti-Semitic in its consequences, a play especially popular wherever Jews have been hated?

Isn't Shylock the most repulsive Jew ever penned, a byword for cruelty, malice and greed?

This is not my reading of the play. Which is not to say that there aren't moments in it that are difficult for any liberal-minded person, Jewish or not, to watch.

"I think it's unquestionably anti-Semitic," the distinguished Shakespearean critic Stephen Greenblatt surprised me by saying when I interviewed him in Venice recently for imagine..., before going on to qualify that judgement with a massive: "Nonetheless..."

"Nonetheless" being "everything one cares about in Shakespeare".

He's right about that. "Nonetheless" takes us into more rewarding areas for conversation than is "Is it this?" or "Is it that?" Shakespeare wouldn't be Shakespeare if his plays weren't by turns both, and then neither.

Charles Dickens, who in Fagin created the second most notorious Jew in literature, could not visit Venice without imagining, 'in the errant fancy' of his dream, that he saw Shylock

It is the distinct, living presence of Shylock, what Greenblatt calls his "inner life", that confounds any simple reading of the play as the expression of a prejudice. For once you see inside those you hate, you see them differently.

In our interviews we found no two people who agreed about the nature of Shylock's inner life, whether it was the inner life of a victim or a scoundrel, whether it revealed a tragic hero or a comic villain.

But whatever position people took, the conversation was never idly academic. To argue about Shylock is to argue about a matter of contemporary concern.

That he has bemused readers for the last 400 years, baffling them as to what Shakespeare intended by him, is testimony to the play's dramatic richness, and is nowhere more apparent than in his association with Venice.

What's he to Venice, when all is said and done, or Venice to him? He isn't the Merchant after whom the play is named. The Merchant is Antonio, for whom Shylock is merely "the Jew". And the play isn't called The Jew of Venice.

Yet for centuries, despite the loathing with which the play's Venetians regard him, and despite the contempt he feels for them and their Venetian allurements - the "vile squealing" and "shallow foppery" which he rightly fears will rob him of his daughter - he has been seen as intrinsic to the city as The French Lieutenant's Woman is to Lyme Regis, or Heathcliffe is to the moors around Haworth.

While for some Shylock re-inforces an ancient hatred of Jews, for others he awakens a sympathy that is beyond time

Once you have read the play you cannot go to Venice and not half-expect to encounter him. Charles Dickens, who in Fagin created the second most notorious Jew in literature, could not visit Venice without imagining, "in the errant fancy'"of his dream, that he saw Shylock "passing to and fro upon a bridge, all built upon with shops and humming with the tongues of men".

And the German poet, Heine, employing a similar language of poetic daydream, didn't just imagine seeing Shylock in Venice but went in deliberate search of him, finding him at last where Shakespeare never put him, in a synagogue in the ghetto, praying in the dark for his daughter.

In his lament Heine thought he heard the "martyrdom which a tormented people had endured for 18 centuries".

Thus, while for some Shylock reinforces an ancient hatred of Jews, for others he awakens a sympathy that is beyond time.

So vividly does Shylock exist for me, too, that in retelling the story of the pound of flesh for a modern audience, I conceive him as a potent presence, not a memory or a phantom, and not in some borrowed guise or equivalent shape, but strictly as himself, a person of now as much as then, a character in the drama and comedy of today.

It was in that spirit that we sought him out when we filmed in Venice. Wondering where he might turn up - by a canal, crossing a bridge, in the ceaseless ebb and flow of conversation of which, after 400 years, he remains the subject.

Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name is published by Hogarth on 9 February 2016. A version of this article was originally published on 23 October 2015.

Howard Jacobson clips

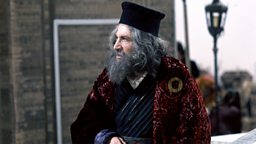

imagine... Shylock's Ghost

-

![]()

Buy on BBC Store

Alan Yentob travels to the ghetto in Venice with award-winning novelist Howard Jacobson.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms