The Renaissance myth: How we got art history wrong

12 February 2016

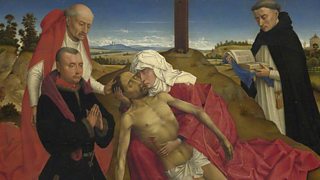

Everyone knows about the Renaissance - it's that golden period when Italy single-handedly reinvented art... except it isn't. As his four-part series, The Renaissance Unchained, arrives on BBC Four, art critic and broadcaster WALDEMAR JANUSZCZAK explains why busting a few myths helps our understanding of a crucial period in Western civilisation.

There are two reasons why I have made The Renaissance Unchained. The first is a fiercely positive reason. The second is more questioning.

The positive reason is, as they say these days, a no-brainer, and can be summed up in two words - the art.

For a couple of weeks we immersed ourselves fully in the delights of the Italian Renaissance

No period in art has stirred up more excitement in me than the great waterfall of creativity that crashed down on Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Renaissance gave us the Sistine Ceiling. It gave us Botticelli's Venus. It gave us the Mona Lisa.

When I was an art history student, way back in the last century, a tour of Renaissance Italy was the highlight of the course. We went to Florence to see the Michelangelos. We saw Siena. We saw Giotto and Piero della Francesca.

For a couple of weeks we immersed ourselves fully in the delights of the Italian Renaissance. And though many years separate me now from that life-changing experience I can still feel its warmth on my back and its intoxication in my head.

So that's the positive reason. I want to get drunk again. The second reason, the questioning one, is more complicated.

By the time I finished my art history course I had what felt like a thoroughly solid grounding in the story of art.

In those days you were taught chronologically. You started with cave art and finished with Andy Warhol.

Watch the series

-

![]()

The Renaissance Unchained

Waldemar Januszczak challenges the myths behind the Renaissance

More on Renaissance art

-

![]()

Botticelli's Venus: The Making of an Icon

Sam Roddick explores the enduring appeal of Botticelli's masterpiece

The great virtue of this chronological approach is that it allows you to envisage the big picture. You know more or less where everything goes; or where it is supposed to go.

However, on modern university courses it has become unfashionable to learn art history that way. Modern courses encourage you to pick and choose what you learn like a punter in a restaurant ordering a la carte.

The thinking behind this tutorial freedom is that you are more likely to engage with subjects of your own choosing and less likely to be misled by imperfect 'grand narratives' created by vested interests in the past.

Art history didn't write itself. Somebody came up with its storylines. And those somebodies had reasons for doing it that cannot always be trusted.

Art history didn't write itself. Somebody came up with its storylines

So which is the best approach?

Having spent several busy decades looking closely at art as a critic and a film-maker, pressing my nose against it and trying to get to grips with its dynamics, I have come to realise – and this will annoy you – that both approaches have their value.

Knowing where everything goes in the story of art is an essential tool of understanding.

If you cannot see the bigger picture, if you do not know where an epoch or a region fits, you cannot build solid foundations for your knowledge.

I have had Cambridge art history graduates working for me who gained double firsts but who could not name an Impressionist painter let alone repeat the dates of the Impressionist exhibitions.

More articles from Waldemar

Art UK: Renaissance

-

![]()

Giorgio Vasari

See 10 paintings by Giorgio Vasari, the 'first art historian'

-

![]()

Rogier van der Weyden

See 22 paintings by the influential Flemish artist

-

![]()

Sandro Botticelli

See 31 paintings by a master of the Early Renaissance

The pick and choose approach leaves gaping holes in which ignorance can flourish.

But the big picture can also be unhelpful. Whoever got their hands on the pen first when it came to the writing of the story of art had a huge advantage when it came to impact and influence.

Their opinions could harden quickly into art historical certainties that were passed from generation to generation. And these weighty certainties were not easy to challenge.

In my case, it took several decades and countless visits to churches and museums before I began to suspect that the story of the Renaissance I had been taught – the one which most of us have imbibed – was profoundly inaccurate.

Yes, marvellous things happened in Renaissance times, but not in the places we have been told, or not for the reasons that have been passed onto us.

Much of this misinformation can be traced back to the writings of Giorgio Vasari, 'the first art historian'.

Yes, marvellous things happened in Renaissance times, but not in the places we have been told

Vasari was a Florentine painter renowned for his speed of work. If you wanted it done quickly in the Renaissance you employed Vasari.

His hero was Michelangelo and when, in 1550, he published his pioneering Lives of the Artists – the first art history book – Vasari made sure that Michelangelo was prominently favoured in the text.

It was in the preface to this Lives of the Artists that the term 'Renaissance' was first employed to describe what Vasari decided was happening around him.

What he proposed was that after the Greeks and the Romans, culture was temporarily lost, and a depressing dark age descended upon civilisation.

This dark age lasted a 1000 years, until the Renaissance came along in Italy, and civilisation was reborn.

Reading his opinion today, you wonder how such a massively biased view could have held sway for as long as it did.

Why didn't thousands of voices pipe up immediately to insist that the Dark Ages were never as dark as Vasari decided?

Why didn't we see quickly that he was a proselytising jingoist cheering on his own side in the great football match of civilisation? Why has it taken so long for us to question Vasari's myth of the Renaissance?

I suspect it’s partly a question of lifestyles. Who doesn't love Italy? The churches? The sunshine? The sun-ripened tomatoes?

In my series I argue that the really critical inventions of the era took place in the north, in Flanders and Germany, where oil paints were developed and sophisticated optics were employed for the first time.

I argue that the really critical inventions of the era took place in the north, in Flanders and Germany

But imagining Andrew Graham Dixon and Giorgio Locatelli sampling beer and mussels in Belgium Unpacked is difficult.

When people make television programmes about the art and food of a region they travel to Tuscany and sip the Chianti. They don't go to Mechelen to eat chips with mayonnaise.

'Twas ever thus. If you were a Grand Tourist in the 18th century, seeking to enlighten yourself on the progress of art, where would you rather have dawdled: Florence or Brussels?

The warm glow of Italy - which I remember so well from my first art historical visit there - seeps into our cultural memories and stays there.

It therefore takes a determined effort to shake these delightful shadows out of our thoughts and replace them with the cold, hard outlines of the facts.

But that's what I've tried to do in The Renaissance Unchained.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms

The Renaissance Unchained is a four-part series broadcast from 15 February 2016 on BBC Four.