From Panama to Sparta: A brief history of leaks

- Published

Say what you like about the recent spate of leaks, none have led to people having their testicles ritually crushed.

Nor, as far as we know, has anyone been locked in a temple until they starved to death. Edward Snowden and Julian Assange are not universally popular, but even their most severe critics have not suggested that their actions provoked a military revolt, or caused politicians to be hauled from their debating chamber and strangled en masse. But all these horrors have taken place during the long and often violent history of leaking, with those exposed by leaks as well their perpetrators at times coming to a sticky end.

Take that fatal enforced malnourishment in a temple, for example. This happened in Sparta around 470BC as a directly result of leaked information.

The leading general and one-time regent, Pausanias, sent one of his slaves with a message to the Persian King. Sensing that something was fishy about this, the slave, Argilios, opened the letter and found that Pausanias was offering to support the Persians if they invaded Greece. More than that, the general suggested that the Persians ought to kill the messenger delivering the letter, just to be sure of secrecy.

Understandably aggrieved at the one-way nature of his errand, Argilios decided to leak the letter to the Spartan authorities. Persia was the mortal enemy of Greece, so the general's actions were seen as nothing less than treachery - and so it was that he was bricked up in the Temple of Athena without any food by way of punishment. Records suggest that his own mother joined the angry citizens who made sure he could not escape.

Ancient Greek politics was a relatively open affair, but Roman civilisation by contrast was positively ridden with plotting and intrigue in its later years, and a fair amount of leaking, according to the historian Tom Holland.

"There was an intense form of political combat, absolutely on the scale of ours today," he says. "You see leaks being used by would-be favourites to destroy their rivals."

Perhaps the most famous leak of Roman times was the pile of documents which appeared on the doorstep of Cicero, Consul of the Roman Senate and a leading philosopher and orator of his time.

Find out more

Listen to Paul Moss's report for the World Tonight on the BBC iPlayer

In 63BC, Cicero had become convinced that a senator called Catiline was plotting a coup, but was unable to prove it. What he found at his door was a collection of letters from allies of Catiline, outlining details of the plot. No-one ever discovered who had passed on this crucial evidence, but flourishing these letters on the floor of the Senate, Cicero was able to convince his colleagues once and for all that the Roman Republic was under threat. It was perhaps as a reward for his dedicated sleuthing, that Cicero was allowed to supervise personally the immediate execution by strangling of all the plotters.

The Roman Empire endured for centuries, its eastern wing surviving as Byzantium right up until 1453 when it fell prey to the Ottomans. Theirs was a civilisation renowned for its tolerance - a multi-nation, multi-ethnic empire with a high degree of what might today be described as social mobility. Even a slave or a eunuch could rise up the hierarchy.

Yet, according to the writer Jason Goodwin, there was one area in which the Ottomans were famously severe. An expert on Ottoman affairs, Goodwin says they were obsessed with preserving secrecy. Many sultans employed deaf mutes around the court, he explains, so that they could not overhear, let alone propagate any information they might pick up.

Sultan Osman the Second had more reason than most to fear leaks. He had decided to crack down on the elite military unit known as Janissaries, who he feared were becoming too powerful. Somehow though, this information did leak out - his own Vizier was later fingered as the source.

When the Janissaries were informed, they stormed Istanbul's Topkapi palace, and it was Osman who suffered the fate of having his testicles crushed before being put to death.

Just as the Ottoman Empire was going into decline, the advent of the modern newspaper in the 19th Century was giving new breath to the fine art of leaking. Now there was the opportunity for leaked information to reach a vast audience, rather than being restricted to those directly affected.

John Nugent of the New York Herald is credited with one of the first great scoops that came from a leak. In 1848, he was handed secret details of a treaty to end the war between the US and Mexico.

His decision to publish led to threats of imprisonment from outraged senators, who held him captive for almost a month. It might well have been worth it though, as Nugent was later promoted to the paper's editorship.

Nugent set a precedent that persists to this day, according to Paul Lashmar, a lecturer in journalism at Sussex University, and a one-time investigative reporter himself. Reporters who get hold of leaks tend to be rewarded, he says, either with promotion, a pay rise or at least with extra professional kudos - even if they do sometimes face threats of imprisonment or worse along the way.

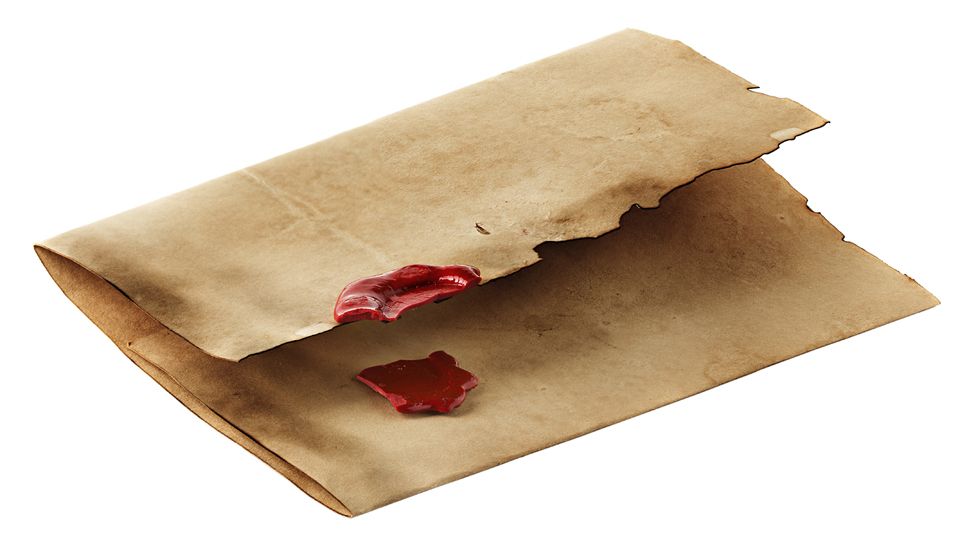

"We would spend long hours in pubs cultivating sources," Lashmar says, rather wistfully. "It could be a police officer, a civil servant, or someone in the accounts department of a company… they passed an envelope over to you and that was great."

The advent of surveillance technology has made this kind of leak much rarer, Lashmar believes. Anyone with a mobile phone can have their movements traced, or they might be picked up on CCTV cameras. He has found public servants, in particular, far more wary of meeting journalists lest they be punished for their indiscretion.

What has replaced the old-style brown envelope is the mass leak, the kind of vast treasure trove of data seen in the release of the Panama Papers, with millions of documents passed on in one go. It is new technology that has made this possible, of course. Earlier great leaks like the Pentagon Papers, which revealed secrets about US operations in Vietnam, had to be photocopied by hand, page after page. Now the entire records of a company or government department can be loaded on to a memory stick with just one click of a mouse.

The campaigning journalist, Heather Brooke, has handled plenty of leaks in her time, and believes this new kind of mass digital leak is here to stay.

"It's very difficult to defend digital information, very easy to attack it," she says.

Brooke argues that those who store digital information have themselves to blame if they find it ends up in the public domain.

"We are in a time when everyone wants to keep every piece of data they can and keep it forever. They are creating a honeypot for hackers, for disgruntled employees, and for people who want to leak."

We have come a long way from the days when a slave messenger could cause havoc in Sparta just by opening a letter. Yet the same asymmetry remains, indeed it is perhaps accentuated. Information is power, and in this early part of the 21st Century, information is also ubiquitous. From the US Army Private Chelsea Manning, to the intelligence contract worker, Edward Snowden, we have seen relatively low-ranking figures get their hands on information and then expose it, leaving those at the top deeply compromised.

Now, more than ever, it seems, the leak is mightier than the sword.

Follow Paul Moss on Twitter: @BBCPaulMoss

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.