Palmyra and the logic of loss

- Published

The list of world-famous historical sites that have been partially or entirely destroyed by recent conflict in the Middle East grows with grim regularity.

In Syria alone, the Great Mosque and the Citadel in Aleppo, the castle of every child's imagination at Crac des Chevaliers, and the ancient city of Bosra have been damaged or destroyed.

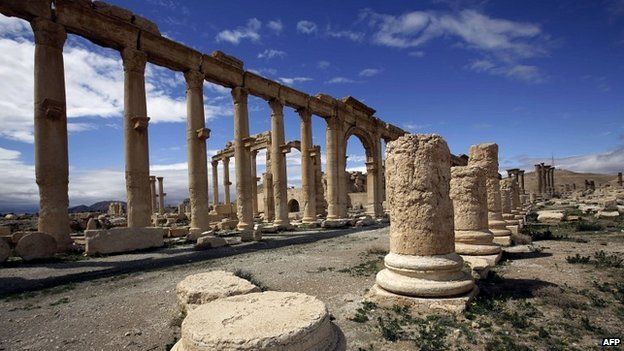

Arguably Syria's most impressive and arresting site, the sprawling ruins at Palmyra (Tadmur to Syrians), is now under Islamic State control and many fear the worst.

Having visited Palmyra and these other sites while studying Arabic at Damascus University back in 2007, I am far from alone in feeling that something truly terrible is happening.

That these symbols from a bygone era might be destroyed by modern-day barbarian forces when they have survived for hundreds or even thousands of years seems somehow deeply offensive and wrong.

Potent symbols

Nevertheless, while I feel an acute sadness at the loss of these sites, I understand those who may feel a certain sense of unease at the outpouring of grief and anguish over their desecration.

Why does IS destroy ancient history?

From this perspective, Palmyra is, after all, a collection of stone; albeit stone exquisitely carved and impressively presented, imbued with huge historical import.

And compared to the staggering loss of life and widespread humanitarian disaster afflicting the Syrian people, bemoaning the loss of a historic tourist site seems crass.

But there are cogent arguments, of course, suggesting that sites like Palmyra are far more significant than that.

Important cultural sites are often pointed to as focal points that can be used to (re)unify a people.

Sites can act as potent symbols of a united past that may cross ethnic, tribal, linguistic, or cultural lines. In essence, their importance can be seen and used as a low common denominator to promote reconciliation in a post-conflict environment.

Distasteful?

Most famously, the reconstruction of the old bridge in Mostar in Bosnia-Hercegovina acted as a focal point of wider metaphorical bridge-building between Serbs, Bosniaks (Muslims) and Croats after the civil war in the 1990s when the bridge was demolished.

As well as being a World Heritage site Palmyra is strategically important, as Jim Muir reports

In Syria, too, there have already been tentative attempts towards this kind of a goal, with meetings between regime and opposition officials nominally in charge of antiquities.

Similarly, the sheer barbarism of IS, exemplified in its brutality against people and against shared cultural monuments, could be a foil to coax more unity among the dispersed opposition groups and factions.

Moreover, these kinds of sites are the heritage and birthright not just of this generation of Syrians so adversely affected by the conflict, but of all Syrians henceforth.

As such, focusing on the protection of sites of great historical concern is just, it can be argued, given that the ultimate goal is to preserve and protect the essential character of a people for hundreds of years to come.

Some may find it distasteful that many seem to be increasingly inured to the human toll in Syria, while interest is piqued by attacks on historical sites.

Doubtless, they might prefer that some of the yardage given over to glossy pictures of Palmyra in its glory days be given over to reporting of the day-to-day devastation faced and experienced by ordinary people.

On the same theme, one can hope and advocate for better, longer, more in-depth pieces or more funding for foreign reporters.

Media storm

A righteous lament this may be, but it is an ineffectual one. The numbing reality is that if these were the types of stories that were demanded, more news services would answer the call.

It must also be remembered that there are rarely mutually exclusive choices here.

The words written and arguments elucidated over the importance of saving cultural heritage sites are also a part of wider discussions and pressure to cobble together anything approaching a meaningful plan to intervene or otherwise halt the worst excesses of the violence in Syria.

The takeover of Palmyra has generated a unique media storm, flinging the Syrian conflict back to wider consciousness. If that can be harnessed in the uphill struggle to galvanise a plan going forward, then no-one will complain.

Whatever the intellectual or moral merits of focusing on such examples of historical desecration, the fact remains that, for me - and I doubt I'm alone - there remains a unique sadness in the loss of such sites.

The abstract and horrifying numbers of deaths that the conflict has produced are not undermined or further ignored, as it were, by the focus on the fate of the likes of Palmyra.

The loss of Syria's cultural heritage represents the loss of far more than some tourist attractions, but the loss of connection between multiple generations.

As with all things, politics is but the art of the possible. So leveraging the fate of these magnificent and important monuments in the wider hope of incrementally building a pressure to bear on the powers that be is a just and vital thing.