Mainwaring and Jones in the new animated reconstruction of 'Dad's Army - A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright - BBC Worldwide)

Broadcast on Saturday 29th March 1969, A Stripe for Frazer was the fifth episode of the second series of Dad’s Army. It was recorded in a single evening’s recording session in studio TC6 at BBC Television Centre on 15th November, 1968.

The episode was made during a key point in the show’s gradual evolution from newcomer sitcom to flagship comedy. It was in this episode that the Verger begins to be established as a recurring character. Mainwaring gets to wear his officer's hat for the first time, and we also get to find out exactly what happened when Sergeant Wilson jilted Mrs Pike at the altar.

Mainwaring puts on his new hat for the first time in this original 1969 publicity image from 'Dad's Army - A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright - BBC)

In short, it’s an important episode and without doubt, one that would still be regularly repeated today, were it not for one fairly significant problem. A Stripe for Frazer doesn’t exist. Or rather it did exist and bits of it sort of still do, however, the original mastertape of A Stripe for Frazer no longer exists in the BBC archives.

Back in the late 1960s, there was no videotape archive at the BBC. There wouldn’t be one until the late 1970s. This meant that after broadcast, virtually all television mastertapes would be returned to the BBC engineering department, who would wipe the tapes, ready to have new programmes recorded on them. This fairly basic act of money-saving recycling means that there are now huge chunks of our television history that simply don’t exist anymore. They’re gone.

Film copies of most major programmes were routinely made at this time, for the benefit of overseas broadcasters. It was one of these copies of the episode that viewers enjoyed in Australia. However, in the 1970s, many film copies were also junked (including A Stripe for Frazer). A 1978 stock-take logged the episode on a growing list of programmes that were ‘missing believed wiped’.

And that’s essentially how it remained until 2008, when BBC WM radio presenter Ed Doolan came forward with a remarkable private collection of audio tapes. In the 1960s and 1970s, Doolan, like many comedy fans of the time made his own home-recordings of programmes he enjoyed. However, in a time when the average home video recorder (the Sony CV2000) cost the same as a family car, if you wanted to record a programme at home, your only real option was to make an off-air audio recording.

Doolan was one of thousands of people who made recordings in this way. Most people never kept them. The usual technique was just to wave a microphone in the general direction of the TV set and hope for the best. However Ed Doolan was different. Not only did he keep his tapes in a beautifully catalogued private archive, but he went to great lengths to make sure his recordings were as good as was technically possible. Essentially, this involved ripping the back off his TV set and hard-wiring a tape recorder into the speaker output at the back. Incidentally this was an unbelievably dangerous thing to do with a 1960s TV set.

As a consequence of his perseverance, many programmes now exist (in audio-only form) that have otherwise been lost from the main BBC vaults.

Doolan later went to work as a presenter at BBC Birmingham and (in 2008) spoke about his collection to a BBC colleague. Paul Vanezis, then a producer on BBC 2’s The Sky at Night. Vanezis was also an archive television specialist, who has done much to help piece together the archives of programmes like Doctor Who, Quatermass and The Sky at Night and recognising the importance of the collection he did his best to go through the massive haul of recordings.

While all this was going on, I was off working for BBC Worldwide (the BBC's commercial arm). I’d been compiling a list of otherwise lost BBC television and radio programmes that might still exist in private collections. The work was primarily intended for BBC Audiobooks.

I was in touch with Paul and learnt of the Dad’s Army recording. I immediately put forward the suggestion that we release the audio on a BBC audio CD, along with one or two other rare bits of Dad’s Army archive. The original idea was to have something ready for Christmas 2009, although, as it turned out, we actually ended up releasing it only last year.

The cover of the 'Dad's Army - The Lost Tapes' CD, containing the soundtrack of 'A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright - BBC Worldwide)

I also had another much odder idea for the Dad’s Army tape, however.

Back in 2006, BBCi (as it was then known) commissioned Manchester’s Cosgrove Hall animation studio to do something delightfully strange with a 1968 Doctor Who story. Just like Dad’s Army, there are a number of Doctor Who episodes that now (either wholly or partially) only exist as audio recordings. What Cosgrove Hall did in 2006 was to take the audio of two of these episodes from the late 1960s and re-create the missing visuals with completely new animation, lip-synced to the existing soundtrack. In effect, the end product was a new Doctor Who cartoon, albeit one featuring the original cast members of the 1960s. It was wonderful and was rightly hailed as such upon its BBC DVD release soon after.

'Doctor Who - The Invasion', released in 2006 by BBC DVD. (Copyright - BBC Worldwide)

Of course, with Dad’s Army we had the same problem. We had the sound, but no pictures to accompany it. In short – an obvious candidate for animation.

I initially began to assemble a team to look at the project in late 2009. The first person to come on board was the artist and illustrator Daryl Joyce, who quickly produced a beautiful piece of concept art of Captain Mainwaring.

Character concept for Captain Mainwaring, by Daryl Joyce. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

Animators Zoran Jankovic and later Chris Bowles also joined us and we worked (entirely independently) on a short test animation, using a raw transfer of the tape. I called up the original camera script, and Radio Times historian Ralph Montagu, kindly traced some publicity images for us, that had been taken on the studio floor during the original recording session. We worked from this material over a period of months to story-board our test sequence, whilst discussing hilariously optimistic potential budgets and time-scales (and generally enjoying a luxury of time that we simply wouldn’t have once the project went into production).

Mainwaring questions his men in this original 1969 publicity image from 'A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright - BBC)

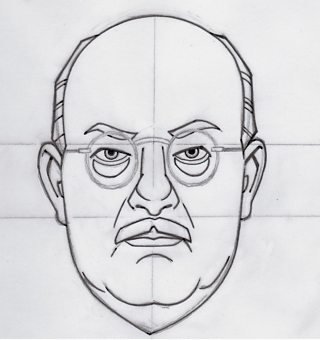

I brought prolific artist Martin Geraghty on board soon afterwards, to handle the character design. I've been a fan of his magnificent work on the Doctor Who Magazine comic strip for a number of years. I was confident he’d be a lovely fit for the project – and so he was. Worked out in pencil and ink, the first of his absolutely brilliant concepts and character breakdowns for Captain Mainwaring were completed around November 2011.

Character drawing of Captain Mainwaring, by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

The first formal pitch for our little project came on 21st December 2012, with a show of our test sequence. This was for BBC Entertainment, in the office of executive producer Caroline Wright. The meeting was at BBC Television Centre, with the studio space in which Stripe for Frazer had been shot just a few floors below us.

A frame from the original animation test-sequence completed in 2012. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

We spent about six months developing the project with Caroline, until around the end of June 2013 and it was a great pleasure to do so. Then we hit a problem.

Rumours had begun percolating through various bits of the BBC that some previously lost 1960s television programmes had been re-discovered somewhere in a film vault in central Africa. However, cards were (with some justification) having to be played very close to people’s chests. Had some lost ‘Dad’s Army’ film recordings been unearthed on a dusty shelf? Was Stripe for Frazer about to turn out not to be so long-lost as we all thought? It was quite possible. However, the parties involved weren’t ready to divulge any information yet. Given the uncertainty, the whole Dad’s Army animation project was quite sensibly put on hiatus - until everyone could be sure what had happened.

It eventually transpired that the source of all these tantalising rumours was the miraculous discovery of nine lost Doctor Who episodes in Nigeria. They’d been found by an independent researcher called Philip Morris, who had personally sifted through various film vaults across the world, looking for otherwise missing BBC programmes. The discovery was announced in October 2013, to much excitement.

The 1968 'Doctor Who' story, 'The Enemy of the World' was returned to the BBC archives in 2013. (Copyright - BBC)

However, there still remained a good deal of secrecy about what other material (if any) may have also been found at the same time. Into 2014, we still didn’t have an answer to the question of whether any Dad’s Army had been rediscovered as well. Finally, in March 2014, I phoned Philip Morris directly to ask if he was yet in a position to confirm one way or the other. There were perfectly reasonable limitations on what he felt able to talk about with regards to ongoing negotiations with other archives. However, after a short discussion of our situation, he was able to confirm that no Dad’s Army had been found in any form.

I went back to the ever-patient Caroline with the good/bad news (depending on how you look at it) and the project was put back on the desk of the commissioners at BBC 2. Sadly however, it seemed we had missed the boat. There had been a number of changes since we’d rested the project and for various reasons, the decision was made not to take things any further.

After over four years working/waiting on the project, it was, needless to say, disappointing to have to break this news to the other members of the animation unit. The decision, not long after, to resurrect the project came about as part of a number of attempts on my part to find someone who might be prepared to pick the idea up again. Having put together such a wonderfully talented team of animators and artists together, it seemed to be so very sad that we might never actually get to work on it together.

One of the many people I approached about this (and various other lost programme animations) was Ben Green, who was (and still is) working on BBC Worldwide’s new BBC Store project. BBC Store was the last chance for the animation project. The project couldn’t seem to find another champion for a while. It was, admittedly, a very unusual idea. However, Ben loved it immediately and so too did everyone else involved at BBC Store. Enthusiastic and supportive, they were all as genuinely excited by the project as we were.

Our eventual executive producer was Paul Hembury – a wonderfully patient and supportive man, who valiantly fought our corner whenever it needed fighting and supported us in every way we could possibly have wished for. Now some way into 2105, news of the forthcoming release of a Dad’s Army feature film, gave everyone a fantastic peg to hang the new project on. With this in mind, a target was set to have our animation completed and ready for release by early February.

This did not give us very much time, to say the least. In fact, after six years of pushing it, we now had only around three months to turn the whole thing around – a good two months less than the five we’d originally hoped for. And much of this time wouldn’t even be spent on animation. All of the character designs and animation kits had to be made up first – an eye-watering amount of work to complete on its own. However, having come so far, we certainly weren’t going to turn down the opportunity now – no matter how late the hours we’d have to put in to get it finished.

A first pass at sound restoration was completed from the original tape at the home-studio of the ever-talented Mark Ayres. And with this, work began in around October 2015, starting with a production meeting at Broadcasting House.

Animation unit members (l to r) Daryl Joyce, Zoran Jankovic, Charles Norton and Martin Geraghty at the start of production on 'A Stripe For Frazer' in 2015. (Copyright - Chris Bowles)

The production line (and that’s pretty much what it had to be) was worked out as a relay from artist to artist. From pencils, to inks, to tracing, to shading, to animation.

First, Martin Geraghty worked out all of the characters and any conceivable facial expression they might have in pencil and ink. A key part of this were the series of mouth-shapes for each and every phonetic position the mouth makes during speech – every ‘ee’, ‘ah’, ‘oo’ and ‘sh’.

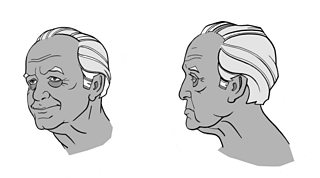

Line art sheet for Sergeant Wilson, by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

The black and white line-art sheets then went up to Ben Morris in Edinburgh, who traced them into the computer using a programme called Adobe Illustrator. This effectively converts the art from a series of pixels into a series of mathematical points. Ben also shaded each character in only occasionally based on notes or guides from myself or Martin.

Shading guide for Private Godfrey. Art by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

Mainwaring and (to a lesser extent) Wilson were the hardest characters to crack it seemed. However, this is probably just because we tackled them first. There’s still a few seconds of an early Mainwaring head-design left in the finished animation (about halfway through the episode).

The trick, Martin found was to get a good balance between a very graphical cartoon of the character and something that communicated the more realistic humanity of the actor. Frazer was probably the most successful. A character like Frazer was always going to be such a gift. Angry all the time, he merely varies between gently seething and absolutely furious. You just need to work within that range. Martin captured him superbly.

Shading guide for Private Frazer. Art by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

Once every element of a character has been drawn out and rendered, the various layers of art were built up in the computer as a kit – one for each pose of each character. These kits started life as sheaves of tracing paper held together with bulldog clips in Martin’s studio. However, by the time they reach the animators, they exist as digital file, which they can cut-up and move about in whatever way needed to create a fully articulated puppet in the animation program.

While all this was going on, our background artist was working on the background plates. This was Daryl Joyce’s part of the process. Keen to try and tap into the aesthetic of wartime cartoon films, I asked Daryl to take a look at some of the light-suffused water-based background paintings in Disney films like ‘Pinocchio’ (1940). The wooden boarded workshop of the carpenter in that film was cited as a key tonal reference for the Dad’s Army church hall set. Just as Disney’s artists had done back in 1940, Daryl also approached these backgrounds principally with pencil and brush – working with the same kinds of water-based gouache paint that would have been available in 1940.

Church hall background plate by Daryl Joyce. (Copyright - The Animation Unit/BBC Worldwide)

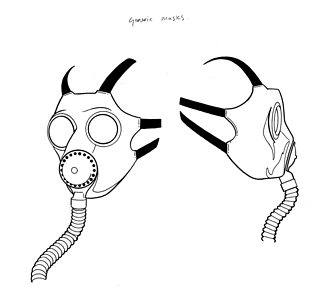

This was a very important part of the overall look of the project. At some stage, each and every element seen on screen in the finished animation was hand-drawn. Nothing was drawn entirely digitally – only traced. So everything from Mainwaring’s football rattle, to the piano in the church hall, to the platoon’s gas-masks started life with a blank piece of paper and a pencil.

Gas-mask element line-art by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

Of course, we were also very keen to match the original television as closely as was practical. The storyboard mostly followed the original shots as laid out in the original camera script. The camera script was an invaluable document, in fact – effectively providing a story-board in written form, from which we could work.

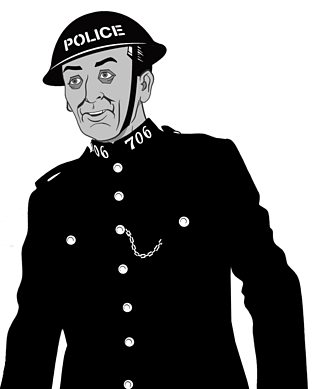

The character of the policeman was the trickiest in regard to getting the accuracy right. We had no photographic reference for him at all. We knew he had been played by an actor called Gordon Peters, but that was all. Happily, I was easily able to contact Peters in person and he was able to help us directly in getting his character looking just right. We also consulted a police historian, to help us replicate the look of an authentic 1940s police uniform. When it came to putting a personal identification number on the policeman’s uniform, we even went so far as inserting a little in-joke, which you will only be able to spot if you really know your early BBC police dramas.

Police officer shading guide. Art by Martin Geraghty. (Copyright - The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

Similar research was undertaken to make sure we had the correct wartime brands of ceiling paint for the church office and contraband cigars for Walker’s bag of black-market goods.

Perhaps the most time-consuming single shot was the opening title sequence. Designed by the criminally uncredited (until now) BBC designer Colin Whitaker, the original opening title animation for ‘Dad’s Army’ was created in 1968, using acetate animation cells. Against all the odds, the original 35mm black and white film inter-positive films still exist and so we had a fresh 1080p high definition transfer struck for us to work from. It was decided from the start that the new animation would be produced in full HD, with an eye on any possible future outlets the episode might enjoy outside of BBC Store.

For obvious reasons, the picture in these original film sequences wasn’t widescreen. Made with the squarer 4.3 television sets of 1968 in mind, none of the BBC’s Dad’s Army film holdings will fit within a modern widescreen television frame.

Traditionally there are two solutions to this issue. You either leave empty spaces (or black bars) to the left and right of the picture. Or alternatively, you crop the top and bottom of the picture until the image is of the right shape to stretch into a modern 16.9 frame. Now, the cropping technique is of course, the work of Satan and you should never ever do it to any archive programme under any circumstances. Cropping destroys the original framing, degrades the definition (when spreading the image out) and often misses out vital picture information. It is, televisually speaking, pure evil.

However, I wasn’t nuts about the idea of black bars either. So, we came up with a third simple solution. And when I say simple, I of course mean, staggeringly complex and time-consuming. We painted new picture information in to the left and right of the existing image area – thus extending the picture across the empty areas to fill the whole frame. The end product is a full high definition version of the Dad’s Army title sequence in true widescreen and with all the film blemishes painted out. The mind-boggling workload of going through each of these near one and a half thousand frames fell to Rob Ritchie, who has done an incredible job.

New widescreen HD title sequence frame, created by Rob Ritchie. (Copyright BBC Worldwide)

By Christmas the number of shots we needed to get through (around 275 in all) was slowly going down. We were gradually getting through it. All the characters had pretty much been drawn and kitted up. And once we’d fixed Frazer’s inexplicably giant head, they were all looking pretty good.

Then I got a call from the lovely Paul Hembury. And it’s a testament here to just how lovely Paul is that I’m still able to call him lovely after he asked me the following question. “Can we move the deadline forward ten days?”

This made things… interesting. There were now only two ways of meeting the deadline. Firstly we brought in some more animators (including the truly amazing Andy Gubba). Secondly, we put a stop to any non-essential luxuries activities like sleeping, eating, or Christmas.

I cannot articulate just how indescribably hard everyone worked during this period. A 3am finish was not unusual. There was scarcely ever an hour of the day when someone somewhere was not working on A Stripe For Frazer.

We finished the last shot with less than a day to spare. Except of course, that day wasn’t really to spare at all. During the animation process you build up a long list of corrections and amendments that you intend to go through fixing in the final week. Only we didn’t have a final week. We had less than a day. We were, in fact, dropping in last minute fixes while the master was being played out to tape on the very day of delivery. And I’m particularly grateful here to Scott Bayliss and Phil Dee at BBC Studios and Post-Production's Digital Media Services, for their infinite patience with us, while we waited for new shots to upload.

Animation program screen-grab from the animation process on 'A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright The Animation Unit / BBC Worldwide)

When that deadline moved, it essentially took away our review time – that valuable period when we all sit down and pick the animation apart and put it back together again – tweaking and fixing one shot at a time. However, I can’t be too hard on it. It’s still a staggering achievement. It just shouldn’t be humanly possible to turn around this much animation with such a small team in such a short space of time.

Adding it up, we turned out around over 46,000 frames in little more than 7 weeks. To do all this to as high a standard as we did (for really very little money) is something that everyone on the project can be immensely proud of. I delivered the final master materials to Paul Hembury on Friday 22nd January 2016 – running through Wood Lane tube station and across the road to a rainy Television Centre just before 7pm.

The final HD CAM SR mastertape for 'Dad's Army - A Stripe For Frazer'. (Copyright - Charles Norton)

These days, Television Centre is largely deserted in the evenings. The letters on the side of TC1 are all dark at night now. The building - empty and still in the Shepherd’s Bush rain. Nearly 50 years ago however, A Stripe for Frazer was being shot here, in the old spur of TC6.

Standing out there on the wet pavement, with the newly animated masters in my bag, it was good to be bringing the episode back home.

Charles Norton is Producer of the animated episode of 'Dad's Army - A Stripe For Frazer'.

- 'Dad's Army - A Stripe For Frazer' is available now from BBC Store.

- Test your knowledge in BBC Radio 4's 'Rather Tricky Dad's Army Quiz'.

- Don't Panic! Just take heed of 'Seven Life Lessons From Dad's Army'.

- Listen to Authur Lowe on Desert Island Discs.