My evil dad: Life as a serial killer’s daughter

- Published

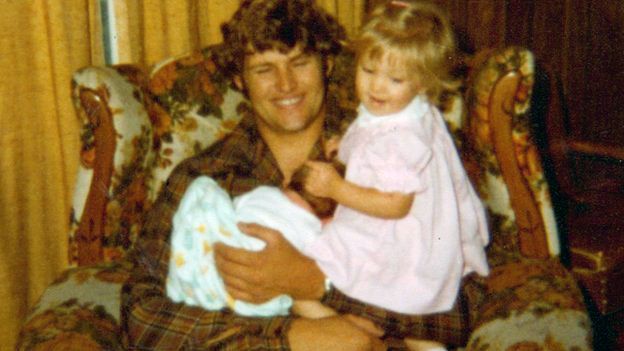

Keith Jesperson is notorious in the US as the Happy Face Killer, who raped and murdered eight women in the 1990s. Here his daughter, Melissa Moore, describes how she learned the truth as a teenager - and eventually found a way to live with it.

Let me tell you about the last time I saw my dad before he was sent to prison. I was 15 years old when he showed up randomly at our home in Spokane, Washington State. He and my mother were divorced, and we just saw him occasionally, when he fitted us in with his job as a long-distance truck-driver.

On this particular day, in autumn 1994, he asked me and my younger brother and sister if we wanted to go out for breakfast with him. We all hopped into his big truck, which had a sleeper cab attached to it. My sister and I sat in the sleeper cab on top of the mattress and my brother sat in the passenger seat.

After we set off, my brother opened the glove compartment and found a pack of cigarettes. He was really shocked because smoking was a big no-no for my dad - that had always been something he wanted to instil in us. And he said, "Oh those are for my friends, for women that I pick up." My brother pulled a face like he didn't really believe him, as if to say: "Dad, are you hiding something from us? Maybe you're a closet smoker."

As we were turning the corner by my high school, a big roll of duct tape rolled out of the sleeping compartment, which struck me as pretty strange too. I thought, "Why does my dad have duct tape by his pillow?" But I kind of brushed it off, thinking, "Well, everything's probably in weird places because there's not a lot of space in here."

My brother and sister had plans that morning so we dropped them off, and it was just my dad and I that went to a downtown diner. I loved my dad, but I didn't really enjoy being around him. He made me anxious. He never molested or beat any of us, it was just a feeling that something was building, seething beneath the surface. I had once tried to articulate it to a school counsellor but it didn't come out right. I mean, a lot of kids think their dad is weird.

One of the things about my dad - which made me very uncomfortable as a young woman - was that he was very explicit about his sexual relationships. For example, he sometimes went into graphic detail about what it had been like sleeping with my mother. He would leer at women in public, make lewd remarks about them, and harass them. That morning in Denny's Diner was no different - I remember him flirting horribly with the waitress while we sat in a window booth.

It was during this meal that my dad said, "Not everything is what it appears to be, Missy." And I said, "What do you mean Dad?"

I watched him wrestling with something internally. Then he said: "You know, I have something to tell you, and it's really important." There was a long silence before I asked him what it was. "I can't tell you, sweetie. If I tell you, you will tell the police. I'm not what you think I am, Melissa."

I felt my stomach drop, like I was on a rollercoaster and had just hit the lowest part of the loop. I had to run to the bathroom. When I returned to the booth I felt calm again and I found to my relief that my dad was willing to just drop the conversation.

But I go back to that incident so often and I think: "If he had told me, what would have happened next? If he had told me about his seven murders - it was very soon to be eight - would I have gone to the police? Having revealed his secrets, would he have given me the chance?"

Could my father have killed me? That has been a huge question mark in my life.

It was a few months after that trip to the diner, in March 1995, that my mother told us three kids that he had been arrested for murder. For murder! It was just overwhelming, and I ran to the bed I was sleeping on and started crying. I couldn't fathom how my dad could have done such a thing.

Then I started to think back to the days when we lived together as a family on a farm in Washington State.

When I was five, I found these beautiful little kittens in the cellar of our farmhouse and I took them outside to play with. When my dad saw what I had in my hands he took them, casually hung them up on the clothes line, and began to torment them. I remembered his enjoyment as I screamed and pleaded with him to take them down. Later on I found their little bodies in the back garden.

Another time, he found me and my brother petting a beautiful black cat. My father is 6ft 6in (198cm) and a big, burly man. He hovered over us, and said, in a playful sort of way, "What have you got there?" He grabbed the cat, but to my relief he started to pet it. Then he began to pin the cat down with one hand and twist the animal's head with the other. The animal was frantically scratching his arms, and we were screaming, but my father had that same strange look on his face - of enjoyment.

He was arrested for the murder of his girlfriend, Julie Winningham, but I was told nothing about what he had done. My mother made it clear that it was not a topic she was willing to discuss. The stifling atmosphere at home did not help me in the long-term, but I now understand that she was trying to protect me.

Throughout that summer of 1995, I sneaked out to the library to read reports of my father's trial. It was during this trial that he confessed to the murders of a number of other women (although he was to recant some of his confessions later).

It was like there was another Keith Jesperson. I had caught glimpses of this other man, but I also remembered when my dad came home from long-haul truck drives he would be so doting and kind. He seemed like such a good dad at times.

Then again, he had said some very strange things over the years. "You know I drove past the Oregon State Penitentiary, and I honked my horn," he told me on the phone one time. "I said: 'Someday I'm gonna be there. But not yet!'"

When I was 13, we were driving along the Columbia River, a beautiful wide river that separates Washington State and Oregon. We were just getting close to the Multnomah Falls area when my Dad announced: "I know how to kill someone and get away with it." Then he just started to tell me how he would cut off the victim's buttons, so that there wouldn't be any fingerprints left, and he would wear cycling shoes that didn't leave a distinctive print in the mud.

At the time, I put this down to my father's penchant for detective fiction, but years later I realised we had been driving through the area where he had disposed of Taunja Bennett's body three years earlier. I think he wanted to relive it and enjoy the moment again. My dad felt compelled to share his crimes, as he did in the messages that he left at truck stops, or sent in letters to the media. They were always signed with a smiley face, leading the media to dub him the "Happy Face Killer".

In 1995, I wasn't capable of balancing out these memories and feelings with the reports I was reading in the library. One day I read an article that quoted Winningham's son, who called my dad a "monster" and said he should be executed. I knew he had every right to say that, but it was just daggers to my heart. I mean, this was my dad!

I stopped reading newspaper reports after that, for my own sanity perhaps. I was able to compartmentalise what my father had done. I thought: he's a truck driver and he comes and goes, now he's gone out of my life for a long time and I don't need to think about this stuff.

I got stared at in high school when the news came out. Parents were really shaken up by the thought that their children might have been in harm's way, so they kept them away from me and I began to feel tremendous guilt and shame.

But during the summer of 1995 I had other, more immediate worries. For a start, I was in a violent, abusive relationship with a boy - something I think my father primed me for.

Somehow I ended up feeling that I had to pay restitution for his crimes. I felt dirty, I felt less of a person, I felt isolated, I felt alone. I used to think that I couldn't live in this world and be a part of it. I would always be a spectator, watching normal people go about their lives.

There isn't a book out there called, What Do You Do When You Find Out That Your Dad's A Serial Killer? There's nothing out there that tells you what to do.

I was also worried. I knew I wasn't capable of killing anybody, I knew I wasn't a sociopath. And yet, didn't I share my father's DNA? How does one become a serial killer? Could that evil be something that I was carrying around, and could I even pass it on to my children?

It became a part of my life that I kept very secret. When I dated boys, I would never bring it up because there's no point scaring anybody away at the beginning.

The Happy Face Killer

- Keith Hunter Jesperson was born in Canada in 1955 - as a child he killed cats and gophers, and attacked other children

- His first known murder was Taunja Bennett, who he raped and strangled in January 1990

- After a couple were wrongly convicted of her murder, Jesperson left "confessions" daubed in the toilets of truck stops and bus stations, signed with a smiley face

- He wrote letters to the Oregonian newspaper confessing to multiple murders

- He once confessed to killing 160 women, but it's now believed that Jesperson killed eight, some of whom have never been identified

But I was lucky enough to eventually find a wonderful man, get married and have my own children.

One day in May 2008, I watched my daughter excitedly jump down from her school bus, bursting with a question that she couldn't wait to ask me. That day in kindergarten they had been learning about family units, and she had been told that everyone in the world has a mummy and a daddy. This was breaking news to her.

"Mummy, everyone has a daddy. Where's your daddy?"

I just froze. I thought: "How do I explain this to her? She's so adorable, she's so sweet and precious - how do I tell her who her grandfather is?" In the end I said, "Oh, he lives in Salem." That was the first thing that popped into my head - and it's the truth. He's in prison there, serving consecutive life sentences.

But I realised that unless I addressed this issue properly, my father's crimes would affect my daughter just as they had me.

We look very alike, she and I. I looked at her face, and it was like a mirror on to the past, on to the little girl I had once been. That was the moment that changed everything. For years I had been living in hiding, but that afternoon, the pain of living with secrets became greater than the pain of speaking out and telling the world who I really was.

I wrote a memoir, Shattered Silence, and I started to give interviews to the media. After I appeared on the Oprah Winfrey show in 2009, I received hundreds of emails from family members of other serial killers thanking me for telling my story, and asking for help and advice.

I travel to see these people or speak to them on the phone. It's given my life meaning and direction.

I've created a whole network of people like me - daughters, sons, siblings, parents and grandparents of serial killers. So far, I have had direct contact with more than 300 people like this - we are an underground community.

Recently I was contacted by the mother of two young girls, whose father was a serial killer who had been all over the papers in Europe. One of these girls was so depressed she was thinking of suicide. I asked my network to write letters to the girls, to let them know it gets better in time.

And it does. All these people have their own story, and each of them is on his or her own journey of recovery. But there are some emotions and processes we all go through. We all have a period of denial, we all ride that pendulum of shock and grief. Then comes the anger.

My father will never get the death penalty for his crimes. But he should.

I don't say that for myself, but for his victims. Justice will never be served to them. I'm not going to go into the details of the horrific torture he inflicted on those poor women, who were mothers and daughters and sisters. Not all his victims have even been identified. There are some parents who still don't know where their daughter or sister disappeared to.

I've spoken with family members of his first victim, Taunja Bennett. They had a lot of details about her life, and who she was as a person, which I really wanted to know.

I've also spoken to his only survivor, who he brutally raped in front of her infant and tried to strangle. She reached out to me, and we arranged to speak on the phone. I was very nervous before the call, and I won't deny it was hard to hear graphic details about her assault. But I believe it was a powerful gift that she gave me. If I wanted to delude myself about what he had done I couldn't any more. I couldn't live in la-la land.

I haven't seen him for almost a decade. After my book came out in 2008, I got a letter from him in which he said, "I don't want the world to judge me as a dad. I was a great dad. My only mistake was my eight errors in judgement."

But he's talking about murders! He's calling them "errors in judgement"! That's the way he sees things. How can anyone - even someone as close as a daughter - continue to have a relationship with a person who so completely lacks honesty and compassion?

For years I kidded myself. I knew he had done terrible things, but I still believed that he loved me and my siblings, that he was capable of love and empathy. Then one day, while I was working on my book, I had a conversation with my grandfather. He told me: "You know, I went to visit your dad in prison, and he said something that surprised me. He said that he had had thoughts of killing you children."

Maybe people won't understand this, but hearing that gave me freedom. It allowed me to see that in truth there had been no double life - there had only ever been one Keith Jesperson and he had been able to manipulate everyone around him and present different facades to the world.

And finally I knew the answer to the question that had been bothering me every time I thought about our last breakfast together in the diner. Would he have killed me if I had told the police about his crimes? Yes, he would.

Understanding that allowed me to say goodbye to him.

Melissa Moore appeared on Outlook on the BBC World Service. Listen to the interview again on iPlayer or get the Outlook podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.