Brain scientists to work with schools on how to learn

- Published

A £6m fund has been launched to make better use of neuroscience in classrooms in England.

The scheme, backed by the Wellcome Trust and Education Endowment Foundation, wants more evidence-based research into how schoolchildren's brains process information.

This could include how the brain's performance is damaged by sleep loss.

The Wellcome Trust's Hilary Leevers says there has been an "evidence gap" in applying neuroscience in schools.

The Education and Neuroscience project wants to fund research that will bring together scientists and educators.

It also wants to replace "myths" about how the brain functions with an understanding based on research.

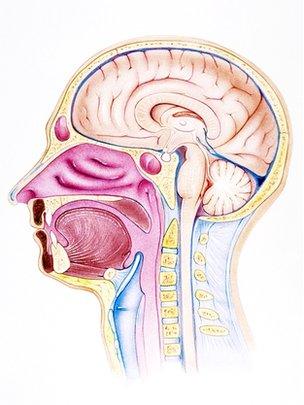

Brain power

Introducing the project at the Education Media Centre, Dr Leevers suggested that while there had been many advances in analysing how the brain worked, they had made little impact on classroom practice.

Where there were computer-based "brain training" exercises being used in schools, she said there was not much reliable evidence to show whether they really brought benefits.

Kevan Collins, chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation, said that schools needed to make better use of the research available - and warned that at present its application for classroom use was "often haphazard and not well informed".

There was a need for evidence-based research that was "politician proof", he said.

Mr Collins said that there were many ideas that "catch on" in schools, with the aim of aiding learning - such as playing music to pupils or making them drink lots of water - but not much clear evidence of what worked.

There was also the risk of doing more harm than good, he warned. He gave the example of the unanswered question of whether extra lessons on Saturday mornings brought benefits or whether they damaged pupils' motivation.

Mr Collins said that the school system should know whether "increasing the dosage" would help or hinder pupils - and this required reliable research.

Lack of sleep

Paul Howard-Jones from the University of Bristol said there may be practical benefits from applying neuroscience research more effectively.

As an example, he said that maths lessons could be improved if teachers had a better understanding of what stimulated the brain.

Neuroscience could also influence the school timetable, he says, if there was evidence that starting later in the day would help teenagers to learn.

The impact of lack of sleep on the functioning of the brain should be considered in the length of the school day and lessons, he said.

Parents also face adverts for computer-based exercises which claim to improve children's learning.

But Dr Howard-Jones said there was no convincing evidence to show whether or not such computer applications could boost academic achievement.

Mr Collins said he was "convinced of the need to do more" to develop and evaluate the use of neuroscience in education.

Sir Peter Lampl, who chairs the Education Endowment Foundation and the Sutton Trust, said: "Knowing the impact of neuroscience in the classroom will also make it easier to spot the plausible sounding fakes and fads, which don't improve standards."

- Published6 January 2014

- Published5 September 2012

- Published7 October 2013