Rescuing Palmyra: History's lesson in how to save artefacts

- Published

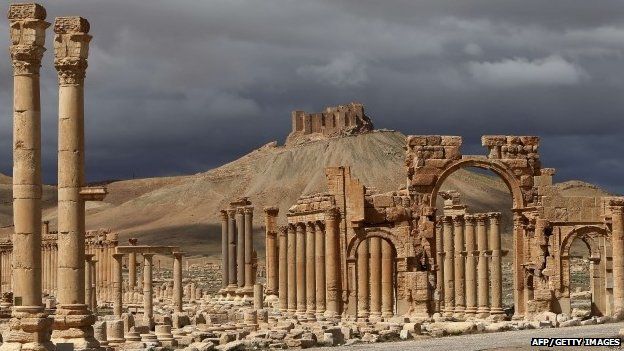

With Islamic State militants now inside the historic town of Palmyra in Syria, the question, inevitably, is whether they will destroy the ancient ruins.

As IS continues to sweep through parts of Iraq and Syria, damage to centuries-old artefacts - because IS sees statues and shrines as idolatrous - is plentiful.

But history has shown that, when culturally important sites are under threat, people will find a way to rally round and save what they can.

Artefacts have been saved in the face of war, natural disaster and genocide - often with seemingly insurmountable logistics and threats to overcome.

Similar efforts have taken place in Palmyra, too.

But how straightforward is it to save what others are determined to destroy? And what are the crucial factors that can help save artefacts?

Mali

In 2012, Islamists seized the historic Malian city of Timbuktu. They started to destroy mausoleums, and banned singing, dancing and sport.

Valuable manuscripts dating back to the 13th Century were under threat - and they ended up being smuggled out of the city right under the Islamists' noses.

It took a group of determined Timbuktu residents, who raised money to pay for bribes and worked out when the militants slept in order to move the papers, mainly by boat.

Staff from two museums provided a safe house for the manuscripts in the capital, Bamako, and helped smuggle them out of Timbuktu in a complex operation.

For the Mali manuscripts to survive, it took co-ordination, planning, bravery and more than a little luck - in that the Islamists did not try to destroy them immediately.

Afghanistan

Years of conflict and Taliban rule saw Afghanistan's national museum in Kabul bombed and looted to such an extent it was feared that nothing valuable remained.

But, to very few people's knowledge, the museum's director and four other men stored 22,000 of the most valuable items in the vault.

It was locked by five keys, one of which went to each man - or to his eldest child if he died. Neither of the men said where the objects were stored - even when threatened at gunpoint.

Some objects were moved into the presidential palace on the orders of President Mohammad Najibullah, whose government fell in 1992.

A curator at the British Museum, where the objects went on show in 2011, said the men were "undoubtedly unsung heroes".

Sarajevo

During the siege of Sarajevo in 1992, the city's National Library was deliberately hit by shell fire, and at least two million books and documents were destroyed.

Many people rushed to the library to save what they could, despite sniper fire from surrounding hills.

But the fire also spurred the head of another library to take action. Mustafa Jahic led efforts to smuggle more than 100,000 books out of his building in banana crates, moving them between safe houses.

He also smuggled equipment through a tunnel near Sarajevo's airport that allowed him to microfilm rare documents.

Why does IS destroy ancient history?

What hope for Palmyra - and Syria?

The advance of IS towards Palmyra gave authorities plenty of warning - a factor that is crucial when it comes to saving priceless objects.

Maamoun Abdulkarim, the director general of Syria's antiquities and museums, said that hundreds of statues and other objects had been moved from Palmyra to safe-houses in Damascus.

"But how do you save colonnades that weigh a ton?" he said. "How do you save temples and cemeteries and, and, and?"

Similar work is being done elsewhere in Syria - largely to take objects out of looters' sights.

Cheikmous Ali is an archaeology professor and founder of the Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology (Apsa), that monitors damage done to Syrian archaeological sites.

"In Aleppo, in particular, there are people who have done some amazing work to protect monuments," he said.

"There are laws that allow you to move artefacts abroad if they are under threat. You have some areas, like Idlib and its museum, that aren't under government control.

"But everything in its museum can't be moved to, for example, Turkey, as anyone who moves it would be considered a thief there and arrested. So everything is still there in Idlib."

The key to saving future archaeological sites is co-ordination, careful planning and an assessment of the safety of the site and of safe houses, said Zaki Aslan, a director of Iccrom, a UN-backed body that works to conserve cultural heritage.

He also urged anyone who wanted to protect rare objects to maintain contact with authorities and to catalogue them thoroughly.

"One can feel helpless but we should try to do something," he said.

"Unesco has called for people to co-operate, for even the people in the conflict to find ways.

"It will be a great loss if even some of the parts of Palmyra are lost. Not just for Syria, but for the world."