Can US manufacturing move from faxes to robots?

- Published

The Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute was officially opened on 11 May 2015

Nestled in the cavernous former site of Republic Windows, external, where over 200 workers staged a sit-down strike, external in 2008 to protest against the window manufacturer's decision to shut the plant, around three dozen people are working on an initiative that could transform the future of US manufacturing.

If all goes as planned, the hope is it will usher in a second industrial revolution - and hundreds of new jobs.

In a high-ceilinged atrium, a faded banner cheerily welcomes visitors "to our grand opening" while signs in bright shades of lime green and purple proclaim "the future is now".

It's a clean, quiet, and largely vacant 94,000-sq-ft (8,700-sq-m) space - not unlike the factory of the future, according to its tenants, the University of Illinois Labs' Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute, external (DMDII).

"It's not going to be a dark and dingy shop floor," Jason Harris, DMDII's director of communications, tells me as he gestures towards half a dozen machines that have been donated by the Institute's corporate partners, including large firms like General Electric and Lockheed Martin.

With a mix of $70m (£46m) in federal funds and over $200m in private investment, the goal of DMDII is to apply research from the consortium's university lab partners in real-world factory settings in order to create a series of software programs and private networks that will usher US manufacturing into the digital age.

The question is whether this initiative, and others like it, will one day lead to the creation of the 200-plus jobs that were lost after Republic Windows drew down the shutters - or whether the factory of the future will be spotless, advanced - and empty.

The facility currently has over 30 full-time employees, with plans to expand this summer

Big effect

Unveiled last month, DMDII is just one of a planned network of 15 manufacturing hubs championed by US President Barack Obama as part of his National Network for Manufacturing Innovation, external (NNMI).

The idea is that by investing in research into applied technologies, the US can give American manufacturers a competitive edge, which will lead to more demand for goods - and more jobs.

"Our first priority is making America a magnet for new jobs and manufacturing," he said in his State of the Union speech, external in 2013.

President Obama has announced the creation of five manufacturing hubs, including one in Raleigh, North Carolina. 15 are planned.

That's crucial, as US manufacturing jobs tend to be higher paying and have a "multiplier" effect. This means that the economic impact of each manufacturing job - in terms of creating supporting positions and sustaining economic activity - is incredibly high.

Furthermore, the US manufacturing sector is a $3tn (£2tn) industry, which represents about 12% of total US economic output, so any technology that can give the sector a competitive edge could have a profound impact.

'Fax machines'

Here on Goose Island - where Chicago's tanneries, soap factories, and coal plants once generated so much exhaust in the late 19th Century that the area was nicknamed "Little Hell" - DMDII is working on reviving the city's manufacturing base by creating digital technologies.

"Manufacturing is very much a pencil and paper industry today - in many parts of the manufacturing sector, the 'state of the art' is using a fax machine to share information," says DMDII's chief technology officer Dr William King, who is also a professor at the University of Illinois.

"It's amazing - you go into a Walmart and there's a whole aisle devoted to wearable computing - you can buy 100 different products for your personal consumer use to digitise your life, and none of that is used in a factory."

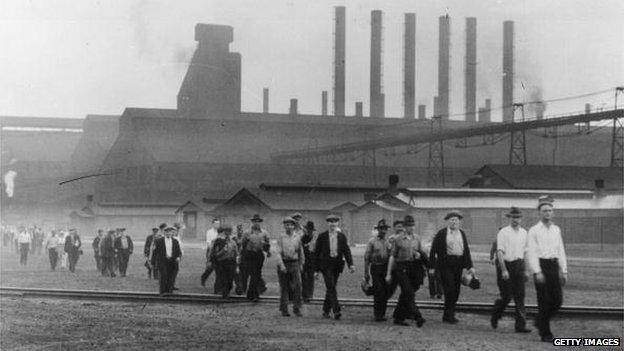

Chicago is known as a metal-working manufacturing hub, partially as a legacy of its steel mills

The way it works is that DMDII issues "calls for proposals" on needs that its 70 industry partners have identified.

Organisations submit plans of action, which the institute can then choose to fund. Five proposals out of 20 have been funded so far, and all must address how the eventual technology can be monetised and sold.

The eventual products could include possible software that would allow manufacturers to retrofit old machines to make them modern, or a manufacturing equivalent of Apple's Siri, in which a worker could ask a digital assistant about a broken part while on the shop floor.

Model for the future

Erica Swinney says when her group first talked about vocational education they were looked upon as "aliens"

To help train workers, an initiative located just a few miles west of DMDII's headquarters - in one of Chicago's most dangerous neighbourhoods - could serve as a model.

The Chicago Manufacturing Renaissance Council was founded by Dan Swinney in the 1980s after he was laid off from his job as a machinist in the first wave of US manufacturing outsourcing.

Mr Swinney initially created the group because "there was the sense that manufacturing is going the way of the dinosaurs - but it was so devastating for working class communities that there had to be something that could be done," says his daughter, Erica, from a booth in MacArthur's, a neighbourhood soul food institution.

In 2008, after noticing that there were still quite a few manufacturers located in Austin who couldn't find workers to fill their jobs, the group started asking why it was that in a neighbourhood where "people are dying because they don't have access to gainful employment" so many jobs were going unfulfilled.

After hearing from employers that the skills students were often taught in high school were useless on modern manufacturing floors, the group founded Austin Polytechnic - a new vocational high school focused on training students so they could get current manufacturing certifications.

Back then, Ms Swinney says most people looked at them like they "were aliens".

"We couldn't find one high school counsellor who would recommend one kid going into manufacturing," she says.

Now, the school has about 120 students - and has been successful in helping low-income students transition into jobs at neighbourhood factories. It was even cited by President Obama as a potential model for training workers in the future.

Austin Poly is one of three schools in the building, located in the Austin neighbourhood of Chicago's west side

Where are the jobs?

In announcing the initiative, President Obama touted that over 500,000 manufacturing jobs have been created since he took office, an implicit argument that the long decline of US manufacturing jobs - which began in the 1970s, but accelerated during the recession - could be over.

Yet the biggest question of all remains mostly unanswered: who will actually be able to man these new digital technologies, which are very different than those currently in use in US manufacturing firms, big and small, across the country?

"It will create jobs but the jobs will be different, and there may not be as many workers on the shop floor," concedes Mr Harris.

Although Dr King and others emphasise that each proposal the institute accepts must include in its plan a way to educate workers for these new digital platforms, there is the basic question of where these employees will come from, given the well-known skills gap that has led thousands of manufacturing jobs across the US to go unfilled.

Craig Freedman says that he has had trouble finding skilled workers in his factory

It's a problem that is already well-known in DMDII's back yard.

Craig Freedman is the chief executive of Freedman Seating, external, which was founded during the World's Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in the 1890s. Now, the firm - located just a 20 minute drive west of Goose Island - has over $100m in revenue and 700 employees.

"Every machine you buy today has some digital component to it - it isn't what our grandparents or parents operated in the day pressing a couple buttons," says Mr Freedman.

"It's going to be a challenge to fill these positions because the technology is outstripping the ability to train workers."

Mr Freedman cites the efforts of the Chicago Manufacturing Renaissance in creating a vocational manufacturing training programme at a local public school, Austin Polytechnic, as a potential model that DMDII could follow.

"I think Austin Poly is one programme that is really working on bringing the skills to the employers and not just training employees for jobs that aren't going to exist."