Body piercing controls wheelchair

- Published

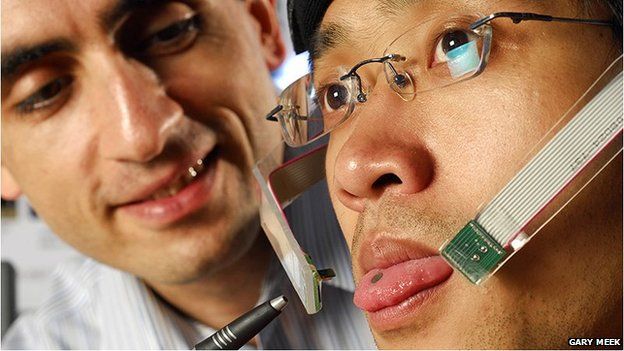

Body piercings have been used to control wheelchairs and computers in a move scientists believe could transform the way people interact with the world after paralysis.

The movement of a tiny magnet in a tongue piercing is detected by sensors and converted into commands, which can control a range of devices.

The US team said it was harnessing the tongue's "amazing" deftness.

The development is reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The team at the Georgia Institute of Technology made the unlikely leap from body art to wheelchairs because the tongue is so spectacularly supple.

A large section of the brain is dedicated to controlling the tongue because of its role in speech. It is also unaffected by spinal cord injuries that can render the rest of the body paralysed, tetraplegic, as it has its own hotline to the brain.

"We are tapping in to the inherent capabilities of the tongue, it is such an amazing part of the body," Dr Maysam Ghovanloo told the BBC.

A lentil-sized piercing in the tongue produces a magnetic field, which changes as the tongue moves. Sensors on the cheeks can then detect the precise position of the piercing.

In the trial, on 23 able-bodied people and 11 with tetraplegia, six positions in the mouth were programmed to control a wheelchair or a computer such as touching the left cheek to turn the chair to the left.

Watch the wheelchair controlled by a pierced tongue courtesy of Dr Maysam Ghovanloo

On average, people with tetraplegia were able to perform tasks three times as fast and with the same level of accuracy as with the other technologies available.

The researchers believe they will be able to have a command for every tooth in the mouth and that by using combinations of tongue positions would be able to develop an "unlimited" number of instructions.

These could dial a phone, change the channel on the television or even type.

Dr Ghovanloo said: "People will be able to do more and do more things more effectively."

He said patients were "all very cool with it" but some older people did not take part in the trial due to tongue piercing reticence.

At the moment the device is limited to university laboratories. The team is trying to fit the sensors into a dental brace to make it more stable on the road, get it approved by the US regulators and come up with a way of getting the expensive kit into the hands of patients.

Dr Mark Bacon, the director of research at the charity Spinal Research, said the ultimate goal remained regenerating the spinal cord but living aids were "needed now".

He told the BBC: "While this may only be beneficial to those with the profoundest motor dysfunction, being able to capture the tongue's complex range of motion to command other assistive devices seems a valuable avenue to explore.

"After all the tongue is capable of the most exquisite commands through the act of speech so why not use that range of motion to command assistive devices more discretely.

"We should bear in mind that the tongue does other things and a smooth and safeguarded mechanism to ensure against potentially dangerous engagement whilst eating, speaking or even swallowing may not be trivial."

- Published7 November 2013

- Published31 May 2012

- Published13 July 2011