Nobody trusts anyone in authority today.

It is one of the main features of our age. Wherever you look there are lying politicians, crooked bankers, corrupt police officers, cheating journalists and double-dealing media barons, sinister children's entertainers, rotten and greedy energy companies and out-of-control security services.

And what makes the suspicion worse is that practically no-one ever gets prosecuted for the scandals. Certainly nobody at the top.

There has always been Us vs Them in modern Britain - but this pervasive mood of suspicion and distrust is different.

In the past it divided along political lines. The Left was for Us and the conservative Right was firmly for Them. But now the politics have disappeared - because no politicians are trusted. It doesn't matter whether they are left or right, all politicians are despised. They will never do anything for the ordinary person - only for themselves and their other corrupt friends in power.

In some ways this is disempowering because it means there is no-one who is both powerful and trustworthy enough to challenge the corruption. But it is also a moment of great opportunity - because the present mood of distrust with authority is very powerful and it could be harnessed to create a new populist movement. This is what someone like Russell Brand has sensed - and is trying to do.

I want to go back and look at the roots of this tearing down of politics and of authority in modern Britain. To do this I am going to tell the story of three rather odd men who in their very different ways helped begin it over thirty years ago.

They are only a small part of a much wider history. But what makes them interesting is that their peculiar stories shine a powerful light on the hidden roots of today's mood of distrust. How really it was taken up with equal enthusiasm by both the political left and the right.

And what makes them even more interesting is that all three are also rather untrustworthy themselves.

The first one is a man called Stephen Knight. He is pretty much forgotten today, but back in the late 1970s he was a journalist and a best-selling author.

Knight is important in this story because his books exposed what he said were hidden conspiracies at the heart of the British establishment. But there is also a surprising, and rather sad, way to get a sense of him as a person.

In 1980 he answered an advertisement in the London Evening Standard. It had been put there by the BBC TV science department and it asked for people who suffered from epilepsy if they would take part in a documentary about the disease.

Knight had suffered epileptic fits for over three years. They were getting worse - and he wanted to know why - so he agreed to take part. Here is a section from the early part of the programme where the BBC filmed him talking to a psychiatrist who specialised in epilepsy.

Knight had been born in 1951 in Essex, left school at sixteen and started working as a salesman in the London Electricity Board offices in Chigwell. But he was determined to be a reporter and at 18 got a job on the local paper - called The Ilford Pictorial.

Knight was very much of his time. A suburban boy, confident and starting to question the paternalism that still wrapped its patronising arms round so much of society in Britain in the early 1970s.

And much of that questioning came from the suburbs - like Ilford. Here is a documentary made in 1969 about how a group of squatters have descended on Ilford and taken over a row of houses in protest against them being kept empty.

It is a big story - and Stephen Knight would have been there as a cub reporter. What's interesting is how the squatters deliberately refuse to be part of old left-wing class politics. Their battle is with the hypocritical council who pretend to care for people but are keeping the houses empty.

It starts with the squatters gathering material to make barriers. They then go to an Indian restaurant where the leader of the squatters holds court. He's called Ron Bailey and he's the star of the film. Ron has arranged for a large demonstration the next day to support the squatting.

It's a great bit of film-making that sharply captures a new mood. It's also very funny. There is a great moment when a post-office engineer turns up and says that the main house the squatters have occupied is not a house but is technically a government office. This causes some confusion - but Ron is is not fazed, his reaction is brilliant.

Stephen Knight did well and moved to the Hornchurch Echo. Then one night he watched a film on the BBC that transfixed him. It was an investigation into the famous Ripper murders in London's east end in 1888.

The programme was presented by two fictional detectives - who appeared in the series Z-Cars - and was full of dramatised reconstructions. But at the end it showed a strange filmed monologue by a real person called Joseph Gorman. He claimed to be the son of the famous painter Walter Sickert (although whether Gorman was really who he said he was would come to haunt Stephen Knight later).

Gorman said that the Ripper was not the mad serial killer that everyone thought - but that the five women had been killed on the orders of those in power in Britain at the time because they knew a terrible secret about the Royal Family.

Here is Gorman - preceded by a bit of the two fictional detectives, so you can get an idea of the oddness of the programme itself.

Gorman said that Queen Victoria's grandson had had an affair with a lowly artist's model, and they had a child. When the Queen and the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury found out about this they decided to cover it up. But a prostitute called Mary Kelly, who knew the secret, tried to blackmail the royal family.

So a group at the top of British society decided to have Kelly killed - along with a group of other prostitutes so as to make it look like the work of a maniac. But, Gorman said, the child survived.

Stephen Knight went to see Joseph Gorman who lived in a shabby flat in North London. He sat for hours listening to Gorman's story. He was fascinated - but was also very suspicious. Knight then went and did lots of research, and he kept on discovering unexplained coincidences that convinced him.

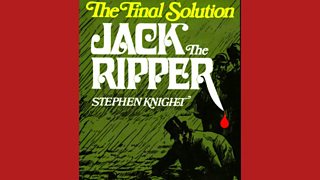

In 1975 he published a book that exposed the conspiracy. It was called Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. It was an immediate best seller. It grabbed the public imagination not just because of the story he told, but because Knight also used the idea of a high-level conspiracy to bring into view a hidden force he said was at the heart of British society.

"Who played the Administration and who the Opposition at any given moment was of minor importance when Britain's entire political system seemed threatened.

What had to be made secure was the sacred Tory-Liberal merry-go-round - the Establishment - which, according to Sickert, had always to rank more importantly in Salisbury's list or priorities than any number of individuals. Hence the impending measures against the women."

What Knight was saying was that the idea there was a left and right battling it out in politics was just a sham. It was a disguise that hid the real network of power and control in Britain - a hidden group at the top of the establishment that looked after itself.

It's important to realise that the idea of "the Establishment" in Britain had only been put forward twenty years before - in 1955 - by a journalist called Henry Fairlie. He had described it as a linked matrix of powerful groups that you couldn't really see in Britain - but you knew were there.

Knight was using the Ripper conspiracy to transform that notion into a powerful cultural myth. It said that the real battle was not in traditional politics, but was against this entrenched group whose informal network stretched into all areas of authority in Britain - be they politicians, senior policemen, or the medical profession.

They pretended to care about you - but really they'd kill you if you threatened their power. Like they had in 1888.

At the same time as Stephen Knight was writing his Ripper book, something else happened in Ilford.

The showroom of the London Electricity Board was robbed by five masked gunmen. It was a dramatic raid because the gunmen shot a policeman, then ran over another - and were chased through east London in a car they hi-jacked at gunpoint.

In January 1975 four men were put on trial for the robbery. One of them is the second man in this story. He was called George Davis.

Here is a report of the raid.

Two of the accused were acquitted. The jury couldn't decide on another. Only Davis was convicted and sent to prison for twenty years.

Davis was not a sympathetic character. He was a petty criminal from Bow in east London who was also a mini-cab driver. But he insisted he was innocent. He said that the police had faked his statement by inserting words he had never said.

But no-one believed him

Except for his wife Rose, and his best friend called Peter Chappell who said he had seen Davis driving his mini cab at the time of the robbery. But no-one believed him either. So Chappell started a bizarre campaign. He drove a van into the front windows of various national newspapers - including the Daily Telegraph. He also smashed it through the gates of Buckingham Palace.

And just to make his point he put his van on the cross-channel ferry, went across to Paris and smashed the windows of the British Embassy.

Then a journalist on the Observer called Robert Chesshyre got interested. But he had to convince his editor. Chesshyre later described the meeting - it's a moment that captures the shift that was beginning in the mindset of the liberal middle classes.

"First I had to convince the Observer's editor, David Astor. He had moulded the Observer as the intelligent liberal flagship of the postwar press, but his interests were, on the whole, affairs of state, national policy, topics of concern to the great and the good.

Would he buy this tale of a hoodlum and his campaigning wife and friend? Astor had two main questions. Did I genuinely think Davis had been wrongfully convicted? And, if I did, was it of consequence, set against the lofty events with which the paper then mainly concerned itself?

Sucking a mint, Astor pondered. It wasn't his sort of story he said finally, but he could see that times were changing and that if a man had received 20 years for a crime he hadn't committed, we shouldn't sleep easy until he'd been freed."

Chesshyre then went off to investigate - and what he discovered was rather odd. He described it in a long article that the Observer splashed on their front page:

"There was no forensic link between Davis and the robbery. The police relied on identification evidence and Davis' supposed statement, which he claimed contained words made up and inserted by a police officer.

Davis was picked out at an ID parade by three policemen, all of whom had been travelling in the same car. At a second set of parades held three months after the crime, 34 out of 39 witnesses failed to pick out Davis. And three made wrong identifications.

Two 'mistakes' were made after Davis swapped his shirt with another man, who was then identified - an odd event at the very least."

Criminals had always known that the police would fit them up if they needed a conviction. But the Observer's reporting, and Chappell's dramatic campaign crystallised a growing feeling among the liberal classes - that maybe those in authority weren't as good as they thought. That maybe the police lied - and sent innocent people to prison.

Chappell carried on with his stunts. He dug up the cricket pitch at Headingley the night before a crucial test match. And there were big marches full of the different groups that were emerging because of the disenchantment with traditional politics - punks, radical lawyers, revolutionaries, east-end squatters and artists, and lots and lots of ordinary people who were shocked by the miscarriage of justice.

Rose Davis called these groups "soap avoiders". She said - "they are very intellectual, but most of them never wash".

But they did her - and her husband - proud. A radical playwright even wrote an agit-prop play about George Davis which was put on at the Half Moon Theatre in the east end. It caused a great fuss and the BBC's arts programme Arena reported on the first night - and interviewed some of the audience about their reactions.

Here's the item. I've included the introduction because it tells you a great deal about the campaign and its supporters - both the dress of the presenter, and her great phrase:

"this really is theatre at the barricades"

Under this enormous pressure the Home Office brought in an outside police force to investigate. What they discovered was so shocking that the Home Office refused to release the report to anyone for 34 years - even to Davis' lawyers.

The Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, ordered that Davis be released from prison - and Davis travelled back to London on a train full of reporters and film crews. It was a hero's return.

Here is Davis on the train - and arriving at Waterloo station.

George Davis' release was just the beginning of a wave of revelations about how the police had ignored the rules, altered and hidden evidence, and faked statements and confessions. Scandals that would include the Guilford Four and the Birmingham Six - and that brought not just the police into question, but revealed how some of those at the very top of the judicial system had known for years that the convictions were unsafe.

It was a bit like what Stephen Knight was saying. That there was an interlinked group at the top of British society who said they worked only for the public good - but really looked after themselves, even if it meant ordinary people were left to rot in jail.

But the experience changed George Davis. Here is an interview with his wife, Rose. She describes how he became a celebrity in this new revolt against those in charge in Britain - but also how she began not to trust him any longer.

But it wasn't just the disaffected left and liberals who were challenging authority. There was an assault simultaneously coming from parts of the conservative right. One of the leading figures in this was Rupert Murdoch who was also convinced that many of those in charge in Britain were hypocrites.

The man who allowed Murdoch to demonstrate this hypocrisy in a dramatic way is the third man in this story. He was called Lord Lambton. But what the events really revealed about power in Britain was far odder and more unsettling than Rupert Murdoch realised.

Lord Lambton was a minister of defence in the conservative government in the 1970s. His family was one of the highest in the land - his ancestor "Radical Jack" Lambton had been behind the Great Reform Act of 1832 which had removed corruption and allowed ordinary people to freely vote for the politicians they wanted.

Lord Lambton was obsessed by his title. When his father died in the 1970 he had wanted to remain as an MP - but that meant he had to give up being an Earl. But he insisted on still being called Lord Lambton. The speaker of the house said that he couldn't, but Lambton insisted he could - and there were endless investigations which couldn't come to any firm conclusion.

In his spare time Lambton went to spend afternoons with a prostitute in a flat in Maida Vale. She was called Norma Levy, and she had quite an odd collection of clients. They included Billy Butlin and John Paul Getty - who used to get her to lie naked in a coffin while he stood in his underpants just watching her.

Lambton was a lot easier - as well as straight sex he just liked smoking cannabis and chatting away to her. But Norma had a devious husband called Colin who decided to make some money. With the help of a reporter form the News of the World, he hid a camera in the wardrobe - and took pictures of Lambton in bed with Norma.

The News of the World also hid a microphone in the nose of Norma's teddy bear.

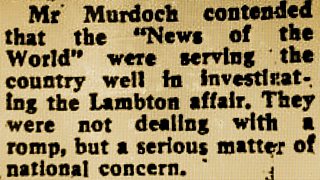

Initially Rupert Murdoch was hesitant - he was worried about the impact such an out and out attack on the government would have. But then he published the story - although he didn't print the photograph, allegedly because of pressure from the government.

Murdoch justified the story like this:

The revelations caused a sensation. And the News of the World produced a great character called Mariella Novotny who was interviewed by the BBC about there was a hidden network of call girls that used a model agency as a front - and had secret lists of those high up in the British establishment.

Novotny has great make up - and I love her observation:

"I've noticed, and found, the higher a man is work-wise, the more blase and pompous he is"

Lambton disappeared - but a few days later he surfaced and invited the BBC's most famous interviewer, Robin Day to come up to the Lambton's stately home in Northumberland.

What then followed was one of the most extraordinary interviews. You would never get anything like it today. Lambton was completely frank and open about what he did. But he does this completely from the point of view of him and his class - and in the process he reveals a brutal self-centred arrogance - especially in how he describes Norma Levy.

Lambton's interview confirmed Rupert Murdoch's view that those who ran the country were a patronising and hypocritical elite.

But the truth about the elite was much stranger and more unsettling. Really those who ran Britain were sleep-walking through a dream world. And many of them had lost touch with reality. And the next stage of the Lambton scandal showed this clearly.

Because Lambton was a defence minister, MI5 were worried there had been a security breach. So a senior MI5 officer called Charles Elwell turned up to interview him. Elwell wrote down the conversation - and Lambton began with an unexpected defence:

"He (Lambton) had never taken any of his papers out of the office. Indeed, he had no need to do so since he had so little work to do. He rather implied that the futility of the job was one of the reasons that he had got up to mischief (idle hands etc)."

I love - "Idle hands etc"

But then, suddenly - almost as if he was embarrassed by what he had just said and wanted to cover it up - Lambton gave Elwell another reason:

"He said that he had throughout his life made use of prostitutes from time to time, but that his behaviour since July 1972 was out of character and had been caused by his obsession over his failure to win his battle to use his title.

This had become an obsession with him to the extent that he was no longer able to read - and he had been a great reader - and had sought to forget his obsession in frantic activity. He had become an enthusiastic and vigorous gardener. Another example of this frenzied activity was his debauchery."

But the MI5 agent sitting opposite Lambton also didn't have anything to do.

Although MI5 told their political masters that Britain was full of Soviet agents - in reality they couldn't find any. Ever since 1971 when over a hundred Russian embassy officials had been deported, the security agency had turned up nothing.

Here is part of a wonderful film that MI5 made to warn of the danger that they were convinced was there. It was shown to anyone who had any access to secret material. The dialogue is brilliant - I'm sure it was written by an MI5 agent.

But the truth was that wherever they looked, the security agents found no hidden danger.

This had an odd effect inside MI5 and Charles Elwell's reaction was typical. He just couldn't believe it - so he convinced himself that mild, liberal organisations like the National Council for Civil Liberties and even the housing charity Shelter were really Soviet-run organisations. (Idle hands etc.)

Elwell's bosses in MI5 began to realise that this was madness. Or as the Daily Telegraph wrote later - "he was over-inclined to see subversion where none existed". Elwell was passed over for promotion.

Which, of course, proved that the MI5 bosses were really Soviet agents themselves

In the late 70s Elwell and a number of other MI5 agents convinced themselves that those who ran the agency were really under Soviet control - as were senior politicians. To get a sense of the crazed mood within the security establishment at the time here is the ringleader of this mad group - Peter Wright - talking about their plot to bring down the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson

By 1980 those in authority were being attacked from all sides. From the left - like Stephen Knight, from the right - like Rupert Murdoch, as well as from within - by the paranoid suspicions of the security services.

If one looks back now it is possible to see it as a kind of revolution in which both left and right were collaborating to overthrow an old, decayed patrician culture. And as it grew in the 1980s and 90s it would give rise to something that went beyond politics - to a general culture of suspicion and distrust of everyone in authority.

But the roots of that revolution were a little fragile.

Eighteen months after George Davis was released from jail as an innocent man - he was arrested again for taking part in an armed bank raid in North London. This time there was no doubt - Davis was found red-handed sitting in the getaway van, with weapons next to him on the front seat.

It was a bit of a shock to his supporters - and above all to his wife Rose. She gave a very powerful interview in which she expressed the deep sense of betrayal she now felt.

Meanwhile Stephen Knight decided he would prove that the British police, and many other groups in the present-day establishment, were secretly run by a hidden network of Freemasons. And he started writing a book that would, he said, expose this

But he too had a bit of a setback. The man he had relied on for his Jack the Ripper theory, Joseph Gorman, went to the Sunday Times and said that he'd made the whole thing up. Knight said that Gorman was lying. He really was Walter Sickert's son, he was just pissed off because he didn't like some of the things in the book.

It did seriously damage his theory.

Knight carried on though, and wrote his book about the police and the freemasons. Again it was a best-seller - because he had tapped into the growing mood of distrust of the police that George Davis had done so much to bring about.

It was very much a product of its time. The central theory about the extent of masonic penetration was very stretched - and at times straight bonkers. But the public were becoming increasingly aware that the police might well be seriously corrupt - and that other groups who might stop this seemed to do nothing. And there were lots of freemasons in the police.

It felt like the book made sense of the new distrust and confusion.

Here is Knight promoting his book on Breakfast TV. It's a great set-up, because the other guest is Dame Edna Everage lying in a large bed in the studio. Barry Humphries - who plays Everage - is very sharp, and you can see him getting interested in the theory.

At the end of the item Edna Everage tries to talk about it -

"It's spooky isn't it, the Freemasons? It intrigues a little bit. Because we live, don't we, in a world of disclosure. Now - you live in a modern world where even a mega-star like myself is filmed in bed at breakfast ......"

The presenter abruptly cuts her off. But it shows why Knight's book was capturing the public imagination.

Then Knight found another fan. He was the comic book writer Alan Moore. He read Knight's Ripper book - and saw something epic in it.

Moore wrote a book called From Hell. It tells the story that Knight put forward - but he turns it into something far grander. The Royal Physician, William Gull - who Knight said did the killings - becomes the centre not just of the vicious conspiracy, but a mad figure seeking to impose narrow order on a fluid world that he can only partially understand.

Even time is fluid. Events from other periods keep breaking through to Gull. The very way we perceive time and tell stories is part of the limitations imposed on us by a repressive society.

What Alan Moore was saying in From Hell was that we see the world in a narrow and limited way that is imposed on us by those in power. But that you can use the imagination to break free from that stranglehold - and make the world anything you want.

It was a very attractive message to a generation who now increasingly distrusted authority - and felt disempowered.

And Stephen Knight's own personal story in a strange way also carries the same message.

In 1980 he had agreed to take part in a BBC documentary about epilepsy. The producer of the film was keen to show a scan of an epileptic brain and Stephen Knight volunteered. He had been hit on the head by a cricket bat when he was a child - and the doctors believed that there was some dead tissue in his brain that was causing the fits.

What the scan revealed was much worse. There was a large shape the size of an egg in his brain. A biopsy was done - and it showed Knight had a cerebral tumour. He was immediately operated on.

Here is the part of the film where he has the scan. It is followed by Knight describing very eloquently what happens when he has a fit. He describes how something inside his brain that he cannot control takes him away from the safety of everyday perceptions to somewhere else.

It's a frightening experience that Knight describes - where "It", as he calls it, leads him to see his own death.

The programme shows how such visions are caused by giant electrical storms that sweep through the neural connections of the human brain.

Some people - hard AI believers - see this as proving that human brains are just complex electrical machines. But that is limited - it is like analysing a film by looking only at the projector.

What Knight is describing is close to what Alan Moore writes about in "From Hell". That the human mind has extraordinary powers of imagination when it is free of the limitations of normal perception.

The present day system of power - that has replaced the old patronising authority - is a new kind of limitation. It treats human beings themselves as very simple machines. Instead of telling them what to do, as the old power used to, the new system increasingly uses computers to read data about what human beings want or feel. And then fulfils those needs.

What Stephen Knight and Alan Moore are pointing towards is something different. How the human imagination has the power to conceive of worlds that have never existed before. And if that imagination can be integrated into a new kind of politics - then those worlds could be brought into existence.

It's unquantifiable and untrustworthy. But it's full of potential.

Stephen Knight died from his brain tumour in 1985 at the age of 33.

Rose Davis divorced George. He then married the daughter of a police inspector.

Lord Lambton went off to live in a villa in Italy - where he gardened frenziedly.