Crystal is 'oldest scrap of Earth crust'

- Published

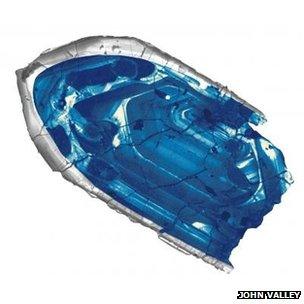

A tiny 4.4-billion-year-old crystal has been confirmed as the oldest fragment of Earth's crust.

The zircon was found in sandstone in the Jack Hills region of Western Australia.

Scientists dated the crystal by studying its uranium and lead atoms. The former decays into the latter very slowly over time and can be used like a clock.

The finding has been reported in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Its implication is that Earth had formed a solid crust much sooner after its formation 4.6 billion years ago than was previously thought, and very quickly following the great collision with a Mars-sized body that is thought to have produced the Moon just a few tens of millions of years after that. Before this time, Earth would have been a seething ball of molten magma.

But knowledge that its surface hardened so early raises the tantalising prospect that our world became ready to host life very early in its history.

"This confirms our view of how the Earth cooled and became habitable," said lead author Prof John Valley, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US.

"We have no evidence that life existed then. We have no evidence that it didn't. But there is no reason why life could not have existed on Earth 4.3 billion years ago," he told the Reuters news agency.

Plate tectonics and weathering have ensured that very little of the Earth's early surface remains to be studied.

Some rock formations that are upwards of 3.5 billion years old persist in select places such as Canada, but the vast majority of Earth's surface rock is modern, less than a few hundred million years old.

The zircons found at Jack Hills are tough pieces of old rock that have been incorporated into the newer, reworked material.

But, barely visible to the naked eye, they still retain insights on the conditions under which they originally solidified.

Previous research had indicated the Jack Hills zircon in Prof Valley's publication to be very ancient, but scientists had concerns that some of its lead atoms might have been lost or even migrated inside the crystal over time.

This would have given the impression the zircon was older than it really is.

However, using two sensitive analytical techniques, Prof Valley and colleagues were able to show the zircon's internal uranium-lead clock was showing a true age.

In doing so, their study suggests strongly a continental crust was present on Earth about 100 million years after the planet formed. And by implication, it tells us that if temperatures were low enough, it could have perhaps even sustained liquid water at its surface.

- Published25 February 2013

- Published8 December 2012

- Published26 September 2008