D-Day 75: How was the biggest ever seaborne invasion launched?

'D-Day Has Come'

By June 1944, the tide of the Second World War in Europe was turning against Adolf Hitler.

The Russians were making headway in the east. In the south, British and American forces had landed in Italy and were slowly moving north. But the most direct route to Germany, through occupied France, lay untouched.

Invading France was no simple task. The Germans were expecting an attack. The north French coast was heavily fortified. Transporting thousands of troops across the English Channel and landing them on beaches in full view of enemy fire risked high casualties. To succeed would require intricate planning, ingenious invention and the mounting of the largest sea and airborne invasion the world had ever seen.

But how did the Allies do it?

A 20th Century Armada

Planning every last detail

The Allied commanders faced a formidable task. The lives of hundreds of thousands of men, and the freedom of millions across Europe, would depend on them getting it right.

Eye in the sky

In the months before the invasion, Allied reconnaissance aircraft flew thousands of hours over northern France. On these daring and often low-level flights, they were unarmed apart from the cameras capturing enemy positions, defences and industry. Within hours, the images would be in the hands of 1,700 photo interpreters who built an incredibly detailed picture of the Allies' D-Day destinations.

'Send us your photos'

As early as 1942 the BBC was asked to issue a public appeal for postcards and photographs of the coast of Europe, from Norway to the Pyrenees. Millions were sent in. Combined with the aerial images, these holiday snaps helped the Allies choose their landing sites, and RAF model-makers used the data to create detailed 3D terrain models.

Beach survey

Small teams in midget submarines conducted covert surveys of the landing beaches to make sure they chose the optimum sites. They analysed water levels, beach gradients and German defensive obstacles and took sand samples to check the beaches could take the weight of Allied vehicles.

When to land

The Allies wanted to land at first light when it was low tide, so hidden obstacles could be seen. British mathematician Arthur Thomas Doodson was enlisted to work out the tidal patterns using mechanised calculators, revealing that 5-7 June would provide the best combination of full moon and ideal tidal conditions.

Dress rehearsals

Rehearsal invasions taught the Allies vital lessons for the real thing. At Slapton Sands in Devon, poor communications meant that men stormed the beach under a hail of live artillery fire, suffering many casualties. Standardised radio frequencies would be essential on D-Day itself.

Weather forecasting

A meteorological team, led by Captain James Stagg, pored over data from observing stations, reconnaissance flights and weather balloons, to work out what the weather conditions would be like in Normandy. Stagg predicted that 5 June would be too stormy for a landing, but a break in the weather would make the invasion possible the next day.

Innovation to overcome the enemy

Under the command of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, Germany had prepared for the invasion its leaders knew would come. The Allies needed to think their way around the formidable firepower, obstacles, and minefields of the Nazi's ‘Atlantic Wall’.

Building a DIY harbour

Delivering an invasion force of the scale of D-Day would require a huge harbour. Capturing one would be far too dangerous; instead the Allies brought their own.

Designed by Major Allan Beckett of the Royal Engineers, the temporary 'Mulberry' harbours were built over six months by around 55,000 workers from 210,000 tons of steel, 1,000,000 tons of concrete. They still stand as one of the greatest civil engineering feats of modern times.

The art of deception

The Allies knew that even with their combined strength of forces they would be up against formidable German defences. Surprise, would be vital. So they created a vast deception to mislead the Germans about when and where the invasion would take place.

Bodyguard

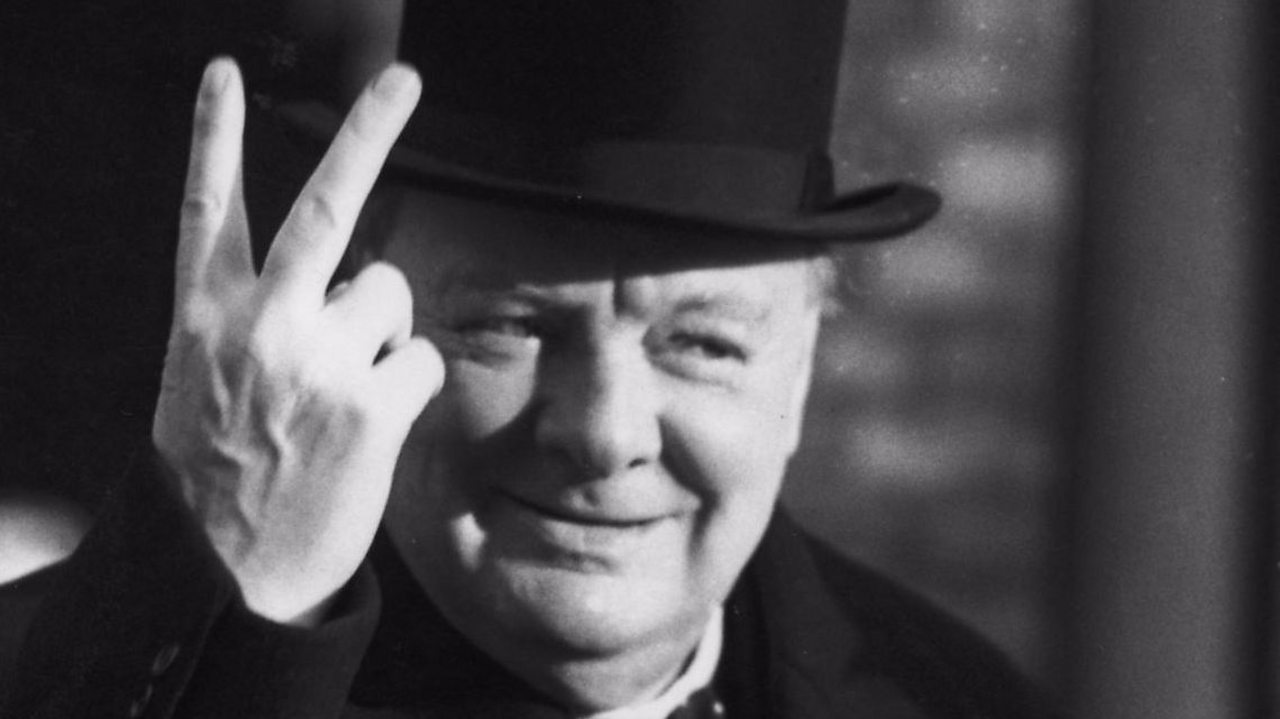

The plan was known as Operation Bodyguard, after Winston Churchill’s comment that in wartime, the truth should “always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

Double cross

The Allies used double-agents to feed information back to their German controllers. Elaborate tricks suggested the Allies might invade across the narrowest part of the English Channel, at the Pas de Calais, or through Gibraltar, and even Norway. Three agents, known as ‘Garbo’, ‘Brutus’ and ‘Tricycle’ were particularly valuable as they were well-trusted by their German controllers.

Artificial army

Backing up the spies' stories were fake armies. The most important of these was the hoax 1st U.S Army Group in Kent, which was placed under the command of U.S General George Patton.

Inflatable tanks

Roads and fields were lined with dummy tanks, trucks and aircraft. Fake landing craft were placed along the southeast coast of England. German Luftwaffe planes were occasionally allowed to fly over to take aerial photographs. The Allies also simulated the radio communications that would be expected for such a group.

Pretend paratroopers

Nearer the time of the invasion the Allies dropped twice as many bombs on the Pas de Calais as they did on Normandy. Even on D-Day itself, Allied planes dropped dummy paratroopers and tin foil to confuse German radar and maintain the idea the invasion would come further north.

Keeping the secret

The real invasion plans were kept top secret, with only the most senior British and American commanders in the know. Movement in the south of England was restricted in the months leading up to D-Day, with a coastal strip up to 50 miles deep in places out of bounds to all but authorised personnel.

Intercepted German transmissions showed that when it came, the Germans were still thoroughly confused as to the time and place of the actual invasion.