Falling in love with medieval armed combat

- Published

Dressing up in uniforms from the past and re-enacting battles is a pastime in many parts of Europe and North America. But, until now, there had never been a world championship for medieval knights.

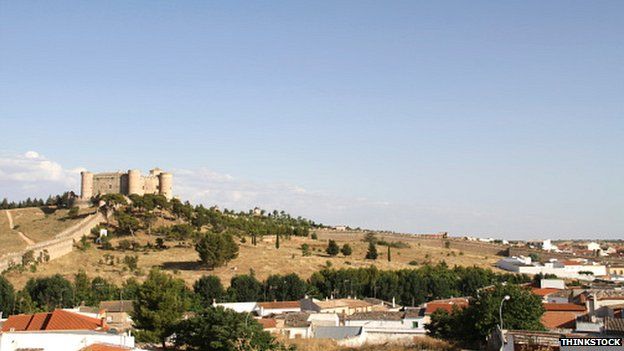

Standing on the great 15th Century battlements of Belmonte - a castle so flamboyantly medieval the Hollywood epic El Cid starring Charlton Heston was filmed there in the 1960s - the view is still one that Cervantes might have recognised.

The interminable duns and khakis of La Mancha are the same that Don Quixote roamed across in his crackbrained quest for adventure.

On my drive south from Madrid, I'd seen wind turbines serried on the horizon, and wondered if even Cervantes' knight would have been mad enough to charge such giants.

But at Belmonte there are still windmills. There are also convents and churches, stone gateways and winding streets.

If you absolutely must dress up in armour, then I suppose it's as good a place as any to do it. Which was just as well. I'd come to Belmonte to attend what was grandly named the First International Medieval Combat Federation World Championships.

To be honest, I wasn't expecting much. I'd been to battle re-enactments before, and always found them rather pointless.

Making my way through the castle to the tournament ground, I saw nothing initially to change my mind.

Women dressed as princesses chatting on mobile phones: check.

Men in Robin Hood caps: check. Striped refreshment tents selling mead: check.

I prepared to be, if not exactly bored, then at any rate justified in my mild hauteur.

I could not have been more wrong.

An opening ceremony which fused Eurovision with Game Of Thrones saw national teams from as far afield as Japan and the US parade down the steep hill from the castle, trailed by pages and wimple-clad WAGs (wives and girlfriends) - and then it was down to business.

And what business! I knew that I'd been wrong in all my presumptions the moment I got to see my first piece of knight-on-knight action: five massive Frenchmen taking on five equally large Swedes.

The action was a whole dimension away from the staged minuet of battle re-enactments.

It was a bit like rugby - only played in full armour. It was a bit like hockey - only with swords and maces. It was a bit like boxing - only with any form of contact, up to and including smacking your opponent around the head with a pole-axe - permitted.

It was violent, it was intense, it was viscerally a sport. Thirty seconds in and I knew I loved it.

I'd come to Belmonte with the aim of exploring what light the staging of combat in full armour today might shed on medieval tournaments.

Plenty, was the answer. When I talked to the contestants, I realised that they had come by an understanding of what it was to fight in plate and helmet that no amount of books could provide.

But I soon realised as well that the championships were situated on the fault-line of an altogether more contemporary question. The resurrection of medieval combat as a sport had begun in Russia - and the Russians were notable by their absence from Belmonte. There had been, I soon discovered, an East-West schism.

"For the Russians, it's about winning at all costs," the German captain, Adam Navrot, tells me, more in sorrow than in anger.

When not dressing in immaculate plate and eagle-crested yellow surcoat, Navrot runs a travel company in Berlin - but he studied the medieval Norman kings of Sicily at university, and has a specialist's fascination with chivalry.

The Russians, I learned, tend to be less keen on the ideal of knightly camaraderie. The previous year, they had taunted the Poles by brandishing a regimental flag decorated with the hammer and sickle.

They had complained about the presence of the Americans, on the grounds that the US had no medieval history.

Their chief administrator had once reached through the fence of the combat area, and held up a Russian knight by his belt to prevent him falling on to the ground. Altogether more Putin, then, than Sir Lancelot.

But Navrot, and the other knights at Belmonte, didn't want to talk about it. They wanted to enjoy the moment - and I couldn't blame them.

As the sun set, heraldic banners fluttered against the blood-red sky, and the lists were crowded with steel-sheathed giants belabouring one another in a spirit of knightly friendship. There probably hadn't been a scene quite like it since the end of the Middle Ages.

Certainly, all I could feel was very jealous. I would have given a great deal, I realised, to be taking part. If only, I found myself thinking, I weren't quite so lanky and weedy.

But then again - it never stopped Don Quixote.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.