“All scriptwriting books are bullsh*t,” said American writer, director and producer Brian Koppelman a few months ago. “Watch movies, read screenplays. Let them be your guide.” He was speaking as part of his series of six-second screenwriting tips on Twitter’s video app Vine. However, he later admitted on his blog that he found some bits of some scriptwriting books interesting – quite a few in fact – and appeared to approve of them as long as their creators were working screenwriters. What he didn’t like, he explained, were people who “give advice for a living.”

These days everyone knows, or likes to think they know, what makes a good script. Because if you can’t tell the difference between an inciting incident and an act two turning point, what are you going to talk about after watching Liam Neeson slam someone’s head into a wall? Who owes who what for the popcorn?

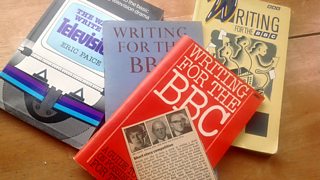

A shelf full of scriptwriting books - but are they any use?

Screenwriting books have helped make a lot of people more informed about how film and television scripts work. They’ve also made their creators money – some of them significant amounts of it. An entire industry has shot up with phrases like ‘a good story well told’ and ‘show, don’t tell’ becoming clichés not dissimilar to the ones writers are told to avoid elsewhere.

I decided to find out whether scriptwriting books really were all “bullsh*t”, by reading as many as I could in two weeks – from recent publications to those from twenty, thirty and forty years ago. While I can’t recommend specific titles here, I give you a twelve-point observational list of what I discovered:

***Sally's twelve-point observational list on scriptwriting books***

- Lists in scriptwriting books help to break up dense information. However, they can end up feeling reductive, particularly when they have pretentious titles (especially ones surrounded by stars).

- Hundreds of thousands of words have been written about creating a succinct story. Scriptwriting books tend to focus on structure more than anything else and yet many feel longer than a George R.R. Martin novel.

- Scriptwriting books repeat the same things in different ways – or sometimes in the same ways. The intricacies of the three-act structure are now seared onto my brain. Lunch has been renamed as the day’s mid-point.

- Tips in scriptwriting books needn’t just apply to scriptwriting. For instance, as well as being something people say about creating scenes, ‘get in late, get out early’ is a great mantra if you have a job you hate (less so if you want to keep it).

- Every scriptwriting book will probably tell you at least one thing that is genuinely new. Many also give an insight into the industry the author works in – whether this is Hollywood or the BBC – in a way that enables you to have a great time imagining what it would be like to steal their job.

- My favourite chapters were the least practical. They discussed questions like ‘What is a writer’s voice?’ ‘Do themes come out of characters, or characters out of themes?’ and ‘Can talent be learned?’ They told me nothing about what pages act breaks should go on.

- The authors of scriptwriting books like charts. And, my god, some of these charts are more complicated than the Hadron Collider.

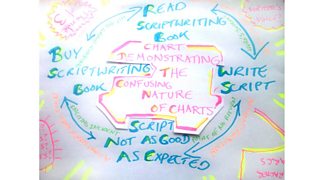

A chart demonstrating the confusing nature of charts (in some scriptwriting books!)

- Scriptwriting books are mostly written by men. I established this by carrying out a rigorous test that involved a five minute glance at the first three pages of results for ‘screenwriting books’ on Amazon. Forty of the authors credited were male and eight were female.

- Some authors of scriptwriting books are more likeable than others. Many have read lots of scripts. This seems to have left them either a) angry that hardly anyone is writing the way they want or b) haunted by the fact they have rejected so many people’s work. In my opinion, the latter are easier to listen to.

- These days, most gurus won’t tell you scriptwriting is an easy way to get rich quick. That was so last century. Instead, they’ll make fun of anyone who does this as a way of demonstrating that they are not selling you a book under false pretences.

- Scriptwriting authors like criticising one another. In a crowded marketplace this is a way they can appear superior. Alternatively, they’ll go for backhanded compliments, such as “well, of course people enjoy so-and-so’s didactic approach; however I personally prefer tangible advice.”

- “All scriptwriting books are bullsh*t” is a sweeping statement that doesn’t really tell you very much. But it is attention grabbing/seeking enough that someone’s bound to write a blog about it.

Unless you’re lucky enough to still have a local library, scriptwriting books generally aren’t free. Their authors might have good intentions and lots of experience, but they also have a vested interest in getting paid. However, just because someone gets paid to do something doesn’t mean that it’s automatically bad. We all need to eat – and books take a long time to write. But before you buy yet another one it’s worth thinking about what you want from it and whether it can realistically give you this.

However interesting, no book can guarantee that you’ll write a better script after reading it. Indeed, a regular complaint in the BBC Writersroom is about writers who know all about structure, turning points and the seven basic plots (or is it three? Or twenty? Or thirty-six?), but have nothing new to say. Their scripts are correctly formatted and have things happening in the right places at the right times, but they feel like they’ve been assembled on a factory production line – one where the workers are chained to heavy machinery and not allowed to see sunlight.

Scriptwriting books from the 1960s - 1980s with a Radio Times cutting.

Times change, and some of the advice in scriptwriting books from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s now seems ridiculous or out-of-date (sometimes both). “Women are no longer simple housewives and Blacks all Bus Conductors” Eric Paice points out in The Way to Write for Television (1981). “The tape recorder not the pen is increasingly the radio writer’s chief instrument” says Norman Longmate in Writing for the BBC (1988). (An earlier version of the same book contains a cutting from the Radio Times for a short story competition. It is dated New Years Eve 1970. First prize is a dishwasher).

The media is changing. It’s becoming more democratic. There are more TV channels than ever before, we can increasingly choose what we want to watch when, and the internet has enabled people to produce their own content more easily. In the future, there will no doubt be new books about new forms of writing that emerge. However, there will also still be all the old ones – perhaps once studied with great seriousness – that have ended up in second-hand shops only to be bought by people like me as an amusing piece of history.

Sally Stott writes about film, TV, theatre and other stuff

You can follow her on Twitter @sallystott