Vigoro: The Edwardian attempt to merge tennis and cricket

- Published

Cricket and tennis compete for people's attention in the summer. One Edwardian man had a dream of ending all this by merging the two sports.

Imagine Andy Murray reaching his hundred at Lord's with a backhand six, or James Anderson serving a hat-trick of aces to win the Ashes back at Wimbledon.

It might have happened. As the 20th Century began, London-based commercial traveller John George Grant felt the division between the summer ball sports of tennis and cricket was pointless and perhaps a wasted opportunity for money-making.

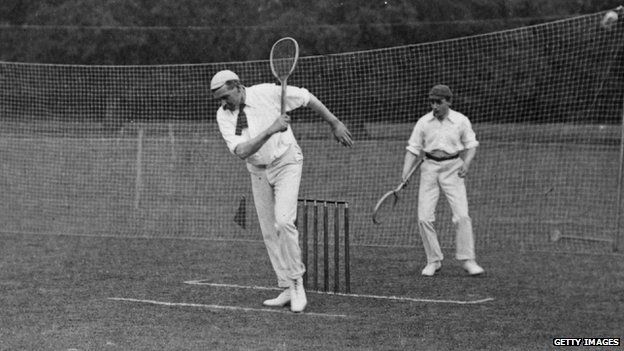

So he invented a quick-moving hybrid version. "Vigoro" saw teams of between eight and 11 players performing like cricketers - bowling, batting and fielding - but using racquets.

A rubber ball was used and six, rather than the usual three, stumps were placed at each end of the pitch.

The press praised the "vigorous, invigorating" game, lacking tennis's spatial restrictions and the physical dangers of cricket. A reporter for New Zealand's Oamaru Mail wrote enthusiastically that "you can hit to your heart's content without being afraid of hearing the ominous 'out of court' from the umpire" and that "you can stop a ball with your head without a risk of seeing a blaze of constellations".

But Vigoro, to which Grant owned the trademark, was a little odd. "Wicketkeeper-bowlers" - who doubled up their skills to prevent time-consuming changes of ends - served the ball tennis-style.

Batsmen had to run if they made contact with it, speeding things up. Fielders were expected to catch the ball by holding the racket at an angle and lobbing it in the air, then bringing it to rest on the face. They returned the ball by whacking it in.

"At that time cricket, along with football, was seen as the sport," says Elizabeth Wilson, author of the Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon. "Tennis was perceived to be more effeminate, more of a social event. Perhaps this was an attempt to turn it into something more masculine. Converting tennis into a team game might have helped that."

The cricket and tennis establishments were initially keen to promote Vigoro. In October 1902, a match took place at Lord's. An eleven led by tennis star EH Miles thrashed the opposition, captained by England batsman Bobby Abel. Games were also played that year, and in 1903, at London's Queen's Club.

Tennis players, more experienced with rackets, were better at it than cricketers. Team scores in Vigoro, counted in runs, were low, generally below 50 - the big wickets and fast serves making it difficult to bat.

A recent experiment where former Wimbledon champion Goran Ivanisevic had England batsman Nick Compton in trouble as the latter faced some tennis serves using a cricket bat, gives some indication of why.

Within a few years of the matches at Lord's and Queen's, the enthusiasm of cricket and tennis's governing bodies for Vigoro had cooled. In 1906 The Sketch magazine asked whether it was "cricket-tennis or tennis-cricket?"

Grant tried to end the confusion by making Vigoro more explicitly like cricket. He created a round-bottomed, long-handled wooden bat. Tennis-style serving was replaced by ordinary cricket bowling.

Grant also developed an indoor version, demonstrated in January 1909 at the Rinkeries, the new roller-skating venue in London's Aldwych. But The Times by now regarded it as a faded gimmick: "The game certainly has some attractive features, and to watch it at a place of entertainment might be more or less interesting, but one imagines that it would be the players who got the chief amusement."

Grant was a nothing if not determined. He visited Australia, where, once again, he tried to inspire a Vigoro craze. To some extent, his efforts paid off.

More hybrid sports

- Football tennis - also known as futnet, this originated in central Europe and involves getting a ball over the net on a tennis court, using any part of the body except the hands

- Polocrosse - a combination of polo and lacrosse, played on horses

- Chess boxing (pictured) - combines chess with boxing in alternate rounds

Women working in munitions factories in Sydney during World War One took to it - it seemed enjoyable and took up little time. Schools started playing it and bookkeeper Ettie Dodge set up a business making Vigoro bats and balls, devoting the rest of her life to popularising it.

Grant's ambition, whether fired by a pure love of Vigoro or an awareness of its commercial possibilities, was undimmed. The game was advertised as "the new health exercise for the world".

By the 1920s Vigoro had lost any association with tennis, apart from the roundedness of the bats. Indeed, this aspect of its history was airbrushed from The Laws of Vigoro, which described it as a "combination of cricket and baseball".

Grant's ambition was now clearly to break into the US market. In 1923 he wrote to the socialite and women's rights activist Alva Belmont, asking for her help to secure demonstrations of Vigoro in New York department stores and promising to create a "tremendous sensation".

He also revealed his frustrations at its failure to catch on more widely: "The Inventor has cheerfully given 20 years with great discouragement all round to complete this work." His plea to Belmont appears to have come to nothing.

Grant died in 1927, leaving Dodge the Vigoro trademark in his will. The game in its amended, wooden-batted form is still being played by women in three states in Australia.

Tennis is now a worldwide game, but top-level cricket is largely confined to the Commonwealth, to the sadness of some fans. "John McEnroe would have been a great batsman," says the blogger Peter Miller, who is writing a history of cricket in non-Test-playing nations. "And Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer, with their supreme hand-eye co-ordination, would probably have excelled too."

Vigoro has been likened in its speed to T20 cricket, now the most commercially successful form of the game. Its current administrators have a more realistic view of its worldwide potential than Grant, but retain some of his hope.

"The time is right for Vigoro to revisit England, its mother country," says Karena Walsh, of the New South Wales Vigoro Association. "I know Australia would be very keen to introduce a new Ashes competition. Grant was progressive and revolutionary for his time. Perhaps we could help to make his dream complete."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.