Warped space-time tips pulsar out of view

- Published

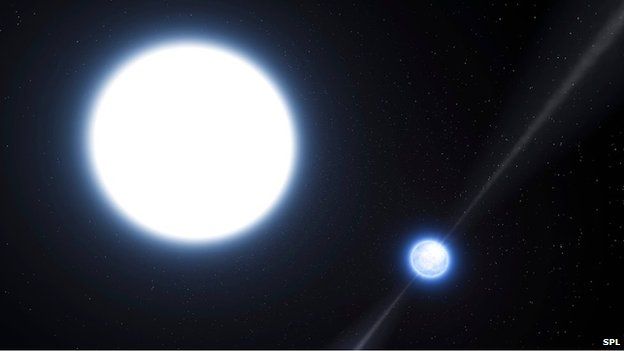

A pulsar, one of deep space’s spinning “lighthouses”, has faded from view because a warp in space-time tilted its beams away from Earth.

The tiny, heavy pulsar is locked in a fiercely tight orbit with another star.

The gravity between them is so extreme that it is thought to emit waves and to bend space - making the pulsar wobble.

By tracking its motion closely for five years, astronomers determined the pulsar’s weight and also quantified the gravitational disturbance.

Then, the pulsar vanished. Its wheeling beams of radio waves now pass us by, and the researchers have calculated that this can be explained by “precession”: the dying star wobbling into the dip in space-time that its own orbit created.

Their findings are published in The Astrophysical Journal and were presented at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

‘Eureka moment’

A pulsar is a small but improbably dense neutron star - the collapsed remnant of a supernova.

“They pack more mass than our Sun has in a sphere that’s only 10 miles across,” said the study’s lead author Joeri van Leeuwen, from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (Astron).

When they occur as binaries, neutron stars come hard up against Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and should generate space-time ripples called gravitational waves, which astronomers hope one day to detect.

This particular specimen, Pulsar J1906, popped up unexpectedly during a survey Dr van Leeuwen and colleagues were conducting at the Arecibo Observatory, Puerto Rico.

“That was a real Eureka moment that night,” he told journalists at the conference.

“It was strange, because that part of the sky's been surveyed lots of times - and then something really bright and new appears.”

They soon discovered the pulsar had a companion star, and that it was pushing the boundaries of what astronomers know of these bizarre systems.

The pair circle each other in just four hours - the second fastest such orbit ever seen - and the pulsar spins seven times per second, sweeping its two beams of radio waves across space to Earth.

Drifting axis

Dr van Leeuwen’s team set about monitoring those waves, nearly every day for the next five years, using the world’s five biggest radio telescopes.

All told, they clocked one billion rotations of the pulsar.

“By precisely tracking the motion of the pulsar, we were able to measure the gravitational interaction between the two highly compact stars with extreme accuracy,” said co-author Prof Ingrid Stairs of the University of British Columbia, Canada.

Each is approximately 1.3 times heavier than our Sun, but they are only separated by about one solar diameter. “The resulting extreme gravity causes many remarkable effects,” Prof Stairs said.

Chief among those is the time-space warp and the wobble that has now caused J1906 to shine its light elsewhere - for the time being.

The pulsar’s axis drifts by two degrees every year, and according to Dr van Leeuwen’s calculations it should swing back around to shine on Earth again by about 2170.

Gravity lab

Prof Tim O'Brien is an astrophysicist working at the University of Manchester and the Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK - one of the facilities that helped track the pulsar.

He was not involved in the research, but told BBC News he had watched the project develop with interest.

"It's a pretty unusual object," he said, adding that tracking it in such detail had been a "big campaign".

"Using these five telescopes all around the world, they effectively accounted for every single one of the billion rotations over five years.

"It's incredible that you can measure all these parameters with such precision.

"These systems are amazing natural laboratories for studying gravity. We were very lucky to catch it for that particular period."

This animation shows the pulsar "wobbling" and its beams beginning to pass us by in 2014

Video edited from original by Dr Joeri van Leeuwen, Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (CC by-SA license)

- Published5 January 2014

- Published4 November 2011

- Published18 September 2006