Viewpoint: Why Islamic State will not endure

- Published

After the shock of Islamic State's (IS) land-grab in Iraq, horrifying videos of hostage beheadings and the public debates about possible terrorist attacks at home and military action abroad, it is unsurprising that people are worried.

Collectively, these factors have made the threat of IS appear greater and the situation more pessimistic than it is.

Of course, IS should be taken seriously and stopped, but the situation is more positive than many think.

IS is not just militarily weaker than it appears, but also its ideology has received a potentially fatal wound.

So far, the group's strategy has not been to directly attack the West - unlike al-Qaeda, which struck at the heart of the US 13 years ago.

The US counter-terrorism response to al-Qaeda's threat, involving mostly drone strikes and special operations, decapitated almost all of its leadership and most of its core operatives.

Over the last seven years or so, al-Qaeda has been reduced by the US from an organisation able to carry out global attacks to one producing out-of-date internet propaganda.

So, it is important to draw confidence from the fact that a movement that directly threatened the West systematically lost its capacity to do harm.

Power struggle

IS vowed allegiance to al-Qaeda's leadership and ideology from the outset.

Mugging operations against other rebel groups in Syria, including the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front, increased its strength while exposing its ruthless totalitarian nature - an inability to reach an accommodation with even those that shared its worldview.

In Iraq, IS achieved what al-Qaeda failed to: territorial control and a self-declared state.

The failure of al-Qaeda to deliver the success it promised allowed IS to feel justified in usurping its erstwhile masters.

The resulting hubris led its commander to declare himself a caliph, offending many al-Qaeda, Taliban and other jihadist groups who felt that their leaders were more theologically qualified for the title.

In doing so, IS has exposed the ultimate trajectory of al-Qaeda's theology. Just as al-Qaeda linked salvation to violence, IS has claimed spiritual supremacy through territorial expansion.

The virulent hostility between the two groups is not over theology but over power and control.

Power lust has virtually broken the already tenuous link between their ideology and religion.

The bulk of Islamic teachings, which relate to mankind's understanding of the beauty of the Creator and of creation, have been eclipsed by a singular bloodlust for power.

The acquisition of religious "authority" through violent territorial control discredits both sides and exposes the fallacy of their myth of brotherhood and a united Ummah (community of believers).

Gains reversed

The territorial gains of IS were not so much due to its strength as to the spectacular failure of the Iraqi army to stand and fight.

Its Shia-phobic stance found ready recruits among the disenfranchised and abused Sunni tribesmen and ex-Baathists, many of whom found it a convenient spearhead for their revolt against a divisive government.

IS boasts of about three months ago that it would capture Baghdad in days did not come true. Instead, some of its gains have been reversed.

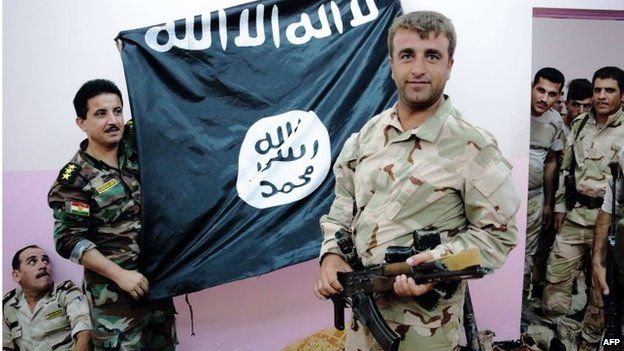

A few weeks ago, it lost the strategically important Mosul Dam to Kurdish Peshmerga fighters supported by US air power.

Desperate to deter the US from continuing to carry out air strikes, IS beheaded James Foley just 48 hours later.

It was a bad decision. The US' most reluctant commander-in-chief was forced to respond.

Like al-Qaeda, the leadership of IS had signed its own death warrant with the blood of the US citizens it murdered.

Civilian factor

On 10 September, President Barack Obama outlined the US strategy to "degrade and destroy" IS.

Its demise will not be quick or easy, but it is inevitable if done without creating new grievances and new ungoverned spaces.

Once under pressure from ground troops and air strikes, IS fighters are likely to melt into urban areas where pursuit will risk civilian casualties.

It is hugely important that both air and ground forces show restraint in those circumstances. Innocent civilian casualties will only create the grievances that sustain these extremists.

Carefully controlled limited operations should allow IS to be cleared from towns and villages progressively over a period of months without unnecessarily risking innocent lives.

However, the decision to simultaneously strengthen opposition to the Assad regime in Syria as part of the new strategy could delay the destruction of IS.

Only a few opposition groups will pass US vetting and may concentrate on IS, but others will continue to fight the government and each other for control of territory. The ensuing chaos could create more ungovernable space for IS to exploit.

If these twin objectives of the strategy are phased, then there is a good hope of success.

Just as with al-Qaeda, military attrition will contain the IS threat but not directly kill its ideology.

Indirectly, loss of territory, decapitation of leadership and ruthless in-fighting will demoralise its followers.

It will deal a severe blow to the notion that its caliphate has divine support, discrediting the modern jihadist idea that political success can be achieved through unrestrained violence devoid of human compassion.

Dr Afzal Ashraf is a Consultant Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi). He was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force and worked as a counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency strategist for the US Commanding General and US ambassador in Iraq, as well as head of the Political Military Section in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.