The international team trying to save Syrian antiquities

- Published

An international group of cultural experts and scientists have formed an emergency task force to help Syrians save their heritage from destruction.

The four-year civil war has killed more than 150,000 people and forced millions more to flee their homes. It is also, as documented by the BBC, destroying some of the world's most important art, buildings and monuments.

"What we're doing is cultural triage," says Brian Daniels of Penn Museum's Penn Cultural Heritage Center, Philadelphia. He has recently returned from an undisclosed location in Turkey where the Heritage Task Force was training Syrians to protect artefacts from bombs and other threats.

"What we're talking about is how do you sandbag collections for safety when you are coming under assault? What gets saved and what doesn't? How do you treat the interior of the building when you expect it to collapse? This is a very grim business."

The Heritage Task Force has been established by the Syrian Interim Government and brings together major organisations such as the Smithsonian Institution, the US Institute of Peace, Penn Cultural Heritage Center and The Day After Association based in Belgium. It is supported by the JM Kaplan Fund in New York.

It is the latest attempt to protect cultural treasures in areas outside the control of the Assad government. In May this year, UNESCO established an observatory in Beirut to monitor destruction and looting while gathering information that may help restoration when the fighting ends.

But the Heritage Task Force is the first direct effort to support and train experts and activists inside Syria who are risking their lives to save the nation's heritage.

"The conditions in Aleppo are particularly bad," says Daniels. "We were meeting with people who had been without electricity for extended periods and without running water for longer than a month. We were meeting with people who had come under regular barrel bomb attack, who were working in museums and other cultural institutions that had had collateral damage from these bombs - sometimes direct mortar attacks."

He says the psychological support is extremely important but admits that the practical help the task force can offer is limited.

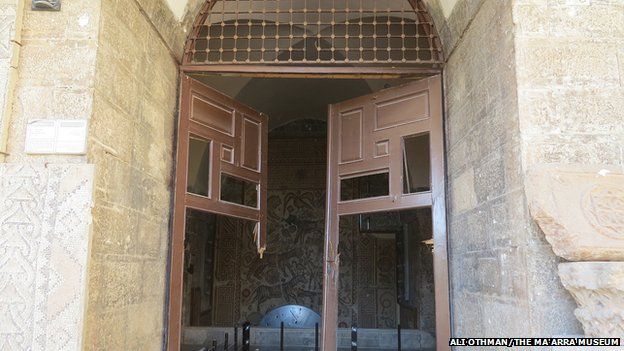

The vast majority of Syria's heritage sites lie directly in the line of fire. Looting is also a major problem. Of particular concern is the condition of a famous collection of Byzantine mosaics at Ma'arra Museum in Idlib province. The building has reportedly been attacked by Isis, an Islamic militant group which is also responsible for a counterinsurgency in Iraq.

The Heritage Task Force has offered advice on how to stabilize the mosaics and provided emergency conservation supplies. Many of the tactics were learned during World War II when Europe's heritage suffered similar threats.

Meanwhile, aerial satellite images have revealed the extent of the damage to an ancient souk in Aleppo and the city's 1,000-year-old Umayyad mosque. Both are UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Further satellite analysis is being planned that will monitor the whole of the country and may offer evidence that some sites are being deliberately targeted.

"Intentional damage is not something we can actually prove with our analysis," says Susan Wolfinbarger, project director of the Geospatial Technologies and Human Rights Project at the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

But she says when the imagery is analyised in conjunction with other information from news outlets, social media and eyewitness accounts, patterns can emerge that may point to deliberate attacks on heritage sites.

War's beginning

Syria is no stranger to conflict. One of the first recorded acts of organized warfare took place more than 5000 years ago at Hamoukar in the northeast. The attackers used clay bullets fired from slings, massacred the residents and burned the city to the ground. Although the region has largely escaped the current civil war, experts say the lack of security makes the site vulnerable to looting and unauthorized construction work.

High- and low-resolution satellite images taken over a series of several years, months and days provide a detailed timeline of physical changes to buildings and landscapes. Such geospatial technology is already being used to offer evidence in criminal cases involving environmental disasters such as oil spills and human rights abuses.

"So many times you have reports of damage or an attack but it's somebody's word and that can be ignored. Being able to use satellite imagery and established scientific methods to analyze that imagery adds so much to the debate and clarifies things that people aren't able to because there isn't access on the ground," says Wolfinbarger.

As the civil war grinds on with no sign of a truce, the task of saving Syria's heritage seems overwhelming.

"To witness these antiquities which have been preserved for thousands of years being destroyed over the course of three years is devastating," he says.

At this point, he says, it is not a question of stopping the damage. They are just hoping to contain it.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.