Conflicted UN struggles in global peace efforts

- Published

Why hasn't the United Nations done more to end the violence in Gaza? Or, for that matter, the conflicts in Syria, Iraq, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Libya, Afghanistan or Ukraine?

These are questions that UN officials find themselves fielding not just with mounting frequency but rising passion and frustration. For it is hard to recall a time when the world confronted so many seemingly intractable crises, and when the body designed to resolve and mediate them looked so thoroughly incapable of doing so.

"Why the UN Can't Solve the World's Problems" ran an accusatory headline over the weekend in the New York Times, a newspaper that's something of a parish pump for UN diplomats.

Just hot air?

Certainly, there is no shortage of diplomatic effort. In February, the UN Security Council evidently had its busiest month since its creation in 1946, mainly because of a succession of meetings on the annexation of Crimea.

For the past two Sundays, Council members have convened at midnight around their iconic horseshoe table. At consultations on the Middle East last week, ambassadors from more than 40 nations spoke in the chamber, in addition to the Security Council's 15 members, in a meeting that took up an entire day. August, which is usually a slow month at the UN, is expected to be unusually hectic.

But to what end? Demands for an immediate and unconditional ceasefire, which is what the Security Council unanimously called for in the early hours of Monday morning, have gone unheeded by both Hamas and Israel.

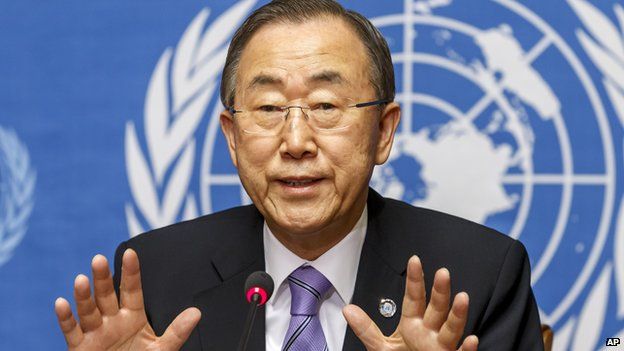

Nor has the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon's shuttle and speed-dial diplomacy so far yielded tangible results. The self-effacing South Korean, now in the seventh year of his posting, often comes across as the ineffectual head of an ineffectual organisation.

His almost daily statements on Gaza run the risk of becoming the diplomatic equivalent of Muzak - background noise that people are vaguely aware of, but do not listen to intently.

Deadlock and dysfunction

For all that, the main reason why the United Nations seems so unproductive is because its member states are so unco-operative. The UN is the sum of its parts, and when those parts work against each other the result inevitably is deadlock and dysfunction.

Its 39-floor headquarters on the banks of the East River in New York can seem like a modern-day Tower of Babel. But again that is primarily the fault of the nations rather than the United Nations. Richard Holbrooke, a former US ambassador at the UN, perhaps put it best. "Blaming the United Nations when things go wrong is like blaming Madison Square Garden when the Knicks play badly."

It is hardly as if the UN is doing nothing. In the present Gaza conflict, the UN is sheltering more than 180,000 people in its schools. At least five UN employees have been killed while working in Gaza.

It is also important to distinguish between UN agencies like OCHA (Organisation for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs), which deliver aid and ameliorate suffering, and UN bodies like the Security Council that regularly stymie those efforts through diplomatic divisiveness.

OCHA has wanted for months to deliver aid over the borders of Syria without the permission of the Assad regime, believing it could boost aid to some 2 million people. But it took months of tortuous negotiations to secure a Security Council resolution because of Russian concerns about the violation of Syrian sovereignty. Russian obstructionism is a recurring problem.

Often the international press corps stationed outside of the Security Council spends more time covering inaction rather than action.

Stymied by veto

The institutional deficiencies of the UN unquestionably exacerbate its dysfunction. Handing a veto to the five permanent members of the Security Council - the United States, Russia, France, Britain and China - was obviously a recipe for gridlock.

But, alas, it was the price that had to be paid to secure the involvement of the major post-war powers, and to give the UN a chance of succeeding where the League of Nations failed.

The United States has used its veto 14 times since the Cold War ended, while Russia has wielded it eleven times. Both countries use their vetoes to protect allies: Israel in the case of America, and Syria more recently in the case of Russia.

Many draft resolutions do not even make it to a vote, because of the threat of veto.

Chill returns

In recent months, a Cold War chill has returned to the Security Council chamber, especially since Russia's annexation of Crimea. Filled with caustic invective and prefabricated soundbites, it has often become a place to air grievances and trade accusations rather than to engage in constructive diplomacy.

The shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 has only worsened the mood. With so many accusing fingers jabbed at the Russians, the chamber has felt more like a courtroom.

That is not to say the body has been completely ineffectual. It has played a crucial role in helping to rid Syria of chemical weapons, following the passage of a resolution last September demanding their dismantlement. It also agreed to send a blue-helmeted peacekeeping force to the Central African Republic, though they have not yet arrived there.

Besides, there are other forces at play that go some way to explaining this period of global disorder.

America, wounded by the long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, is understandably reluctant to play the role of global policeman and to project its military power. But the corollary has been a diminution of the Obama administration's diplomatic clout, whether in Tel Aviv, Cairo, Kabul or Baghdad.

Seizing on this moment of American weakness, Vladimir Putin has sought to extend Russia's influence, even if it has meant flouting international law and norms, as has been the case with the annexation of Crimea. The new world order supposedly ushered in by the end of the Cold War has given way to a new world disorder.

So the UN is something of a bipolar organisation, at once active and inactive. But the main blame lies with the member states themselves: nations that are far from being united.