When gin was full of sulphuric acid and turpentine

- Published

It's 250 years since the death of William Hogarth. His famous work Gin Lane still informs the way people think about the drink.

It's arguably the most potent anti-drug poster ever conceived. A woman, her clothes in disarray, her head thrown back in intoxicated oblivion, allows her baby to slip from her grasp, surely to its death in a stairwell below.

She's the centrepiece in an eye-wateringly grim urban melee - full of death, misery, starvation and fighting.

The year was 1751. The drug in question was gin. And the engraving was a conscious effort by William Hogarth, along with his friend novelist Henry Fielding, to force the government to do something about a drink that was threatening to tear apart the social fabric of England.

The craze had started with changes in the laws at the end of 17th Century aimed at curbing consumption of French brandy by liberalising the distilling industry.

The Glorious Revolution in 1688 saw the arrival of William and Mary, from the Netherlands, to topple James II. The Dutch influx brought a new spirit - genever - which rapidly caught on in England.

"There was a good chance in the 18th Century that the gins being drunk in London were genever-style," says Gary Regan, author of the Bartender's Gin Compendium. "A lot of it was probably really terrible. People were distilling in their houses."

Of course, the genever being drunk by William III and his successors was not easy to replicate in a bathtub in a basement. The eager entrepreneurs reached for just about any additive they could in an effort to make the drink even vaguely palatable.

Types of gin

Genever, Jenever: Dutch spirit, still immensely popular in the Netherlands today. Distilled from malt wine and flavoured with juniper, hence the name jenever. Also referred to as Madam Geneva in English.

Old Tom Gin: Now used to refer to a style of gin popular in England in the 19th Century. Typically sweeter than modern gin. Various explanations for how name came to be. Traditionally often featuring some sort of cat on the bottle.

London Dry Gin: Modern style of gin, which has dominated since the late 19th Century.

Plymouth Gin: Similar to London dry gin, although said to be slightly sweeter, and the subject of protected geographical indication status, meaning it can only be made in Plymouth.

Sloe Gin: A liqueur made from gin and sloe berries from the blackthorn.

"You had a poorer populace who aspired to drink like the king," says Lesley Solmonson, author of Gin: A Global History. "They wanted novelty. But the poor couldn't afford the genever that the king was drinking."

Instead home distilling operations mushroomed, with some areas having every single building churning out bad gin.

"They were using sulphuric acid, turpentine and lime oil," says Solmonson. "It was like death in a glass. One tankard could kill you."

"People were drinking to forget their misery. These gins were roughly double what the proof of a modern gin is. And they were drinking a whole tankard of it."

For even the most virtuous pauper, temptation was hard to avoid.

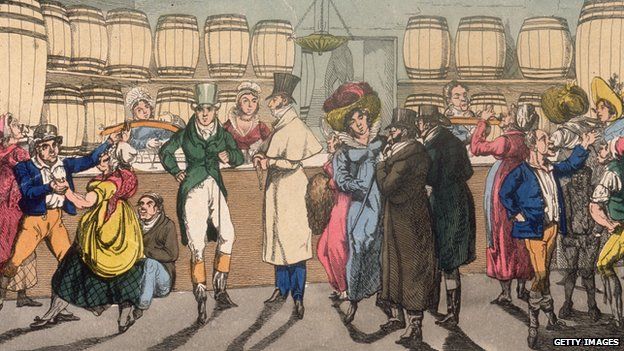

"It was ferociously adulterated," says Jenny Uglow, author of Hogarth: A Life and a World. "And it was sold everywhere - in grocer's shops and ship's chandlers. There was a bar in every building. It has been said that it tasted more like rubbing alcohol."

The first half of the 18th Century saw rapidly escalating concern over the new drug's effects, as the records of the Old Bailey show.

Take the case of William Burroughs, charged with assault and robbery in 1731. The court heard: "He drove hackney Coaches, and by that means fell into that dreadful Society of Gin-drinkers, Whores, Thieves, House-breakers, Street-robbers, Pick-pockets, and the whole train of the most notable Black guards in and about London."

Or James Baker, convicted of robberies in 1733. The court records say: "He was one of them who frequented Gin-Shops, where he got into acquaintance of the vilest Company in the World, who for two or three Years past, drove him headlong to destruction, and into all kind of Villanies."

But arguably the most shocking case of the era was that of Judith Defour, convicted in 1734 of taking her daughter out of the workhouse and strangling her in order to sell her clothes to raise money to buy gin. She confessed and was hanged.

There was legislation throughout the first half of the 18th Century but nothing that adequately tackled the issue. Hogarth and Fielding thought they could finally be the ones to get the message across.

Fielding's contribution was an investigation into the crime, entitled an Enquiry into the Late Increase in Robbers. "Fielding was a magistrate," says Uglow. "It was very much a case of trying to solve an urban crisis that gave rise to a lot of other crime and domestic abuse and violence and robbery. The demon drink was an instrument of wider and deeper social malaise."

Hogarth's engraving, paired with its companion Beer Street, singing the praises of a much weaker drink, hammered the message home. Gin was evil. Beer was good.

Not that those lying around sozzled in basements were moved by the engraving. "I shouldn't think the people drinking the gin took too much notice but the people living and working among them did," says Uglow.

"Engravings would have been bought by opinion formers. But they also hung in the print shop windows."

Soon a new law followed. "This new legislation came a few months after the prints were published," says Val Bott, of the Hogarth Trust. The Gin Act 1751 effectively eliminated most of the smaller gin shops, where the worst excesses occurred.

William Hogarth 1697-1764

- English artist, satirist and social reformer

- Other famous works include A Rake's Progress, Marriage A La Mode, and Heads Of Six Of Hogarth's Servants

- Made living by selling engravings of his work, rather than relying on rich patrons

Hogarth and Fielding recognised the underlying problems. The desperate poor were driven to drink. The mere existence of gin didn't cause the social problems.

"Gin Lane is about the destruction of the social fabric. But it is not snarky, it is not getting at the poor," says Uglow.

"Hogarth was very concerned about the children - the future of the nation."

The legislation of 1751 only really targeted the tipple of the poor. "It was a time when many drank heavily," says Uglow. "There was the four-bottle man in the club drinking claret and port. There was no crackdown on that."

There was a decline in gin consumption after the 1751 act, although some historians blame either rising grain prices or a switch to other drinks.

Gin wasn't dead. But it did change.

"I don't think the sort of thing we are interested in today, with elegant botanicals, would have been recognisable to Hogarth," says Bott.

But there is at the moment, with the decidedly retro-obsessed cocktail trend, greater interest in the history of gin than ever before.

In 1830, the invention of the Coffey still changed the way gin was made. By the end of the 19th Century, the London dry gin style, familiar to modern drinkers, was dominant.

Drinks giant Diageo has just launched Tanqueray Old Tom Gin, referring to a type of slightly sweeter gin believed to be a "missing link" between the horror of Hogarth's gin and London dry gin. The new formulation uses a recipe from the archives of Charles Tanqueray in the 1830s.

Tanqueray joins other brands of Old Tom Gin being bought by cocktail enthusiasts, including Hayman's and Jensen's in the UK, and Ransom in the US.

There's a colourful story behind the name, says Hayman's director Miranda Hayman. She is the 5th generation of a gin distilling family. Her great-great grandfather was James Burrough, who created Beefeater gin in the late 19th Century.

"A gentleman called Captain Dudley Bradstreet got a figure of a cat put outside his house. If you put money in the mouth, a shot of gin would come out of the paw."

Another less exotic explanation is simply that Old Tom was named after a distiller, Thomas Chamberlain.

Gin cocktails from BBC Food

We'll never even know if the taste of the modern Old Tom Gins are anywhere near to the gin of the early 19th Century.

But what we do know is that gin was left, at least in part thanks to Hogarth's propaganda, with a slightly grubby reputation, long after the poisons were removed and the proof was lowered.

Use the expression "mother's ruin" and people know you're referring to gin.

And consider the number of people who avoid gin, while stating it is a depressant. It is, but only because all alcohol is a depressant. Any extra effect is entirely psychosomatic.

So if you feel gin has a particularly bad effect on you, perhaps you should blame Hogarth. His depiction has been hard to shake.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.