How my grandad survived the Holocaust

- Published

Events are taking place around the world to mark Holocaust Memorial Day.

Harry Spiro was eight years old when World War Two began in 1939. He was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust.

He was 14 when the war ended, which he says was like living "hell on earth" that "you couldn't do nothing about".

It's thought more than six million Jews were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust. Some estimates of the total death count are at 11 million.

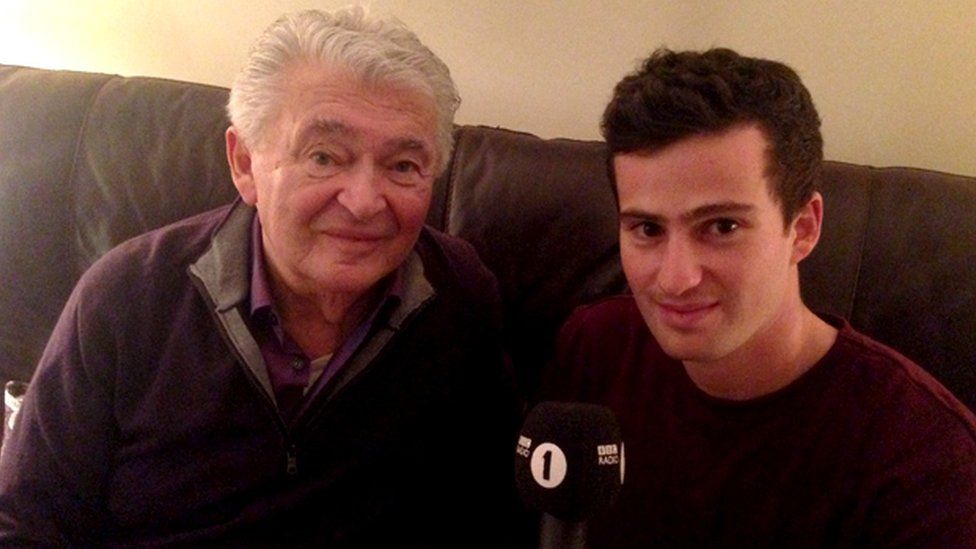

Harry spoke with his grandson Stephen Moses about what life was like during the holocaust and how he feels more than 70 years on.

Harry's story

"The first time I saw a tank in the town, I remember vividly that it was a very hot day," Harry begins. "The soldiers wanted cold drinks of lemonade and as a child it was something new to me."

Harry is from the Polish town of Piotrkow, which in October 1939 became the first ghetto set up by the Nazis in Poland.

A ghetto during World War Two was an area in which Jewish people were forced to live in.

Harry recalls: "I remember the first announcement they made saying every Jew had to wear an armband with a yellow star of David and in it was written 'Jew'. It didn't mean much to me.

"Next they put out notices saying any Jew who would step outside will be shot."

The leader of the Nazi party in Germany, Adolf Hitler, believed Jewish people needed to be removed from society and viewed them as a problem.

Harry says the streets he used to play on with his friends and cousins quickly became alien to him.

"The soldiers were patrolling the streets with their dogs. The dogs were trained to get the Jew. You didn't have to do anything - if you were two or three people standing or talking the orders would be given - get the Jew.

"Very often they would do it for their own enjoyment and I would think it was very strange the Germans were laughing and terrorising us kids.

"They did it to put fear in the community and they certainly succeeded," Harry tells his grandson, Stephen.

"Within a few weeks they rounded up some lawyers, doctors and community leaders. In total about 25 people and the Germans shot them.

"There was no reason or explanation. Very few people saw [it happening] but you saw the dead bodies.

"They didn't bury the dead right away, that was very disturbing. People were asking, 'Why?' but nobody had the answer.

"We accepted it. The people accepted it. You couldn't do nothing about it, but you kept on."

Harry worked in a glass factory in the town to help support his mother, father and his sister who was two years younger than him.

In September 1942 the Germans announced that anyone who worked in the glass factory should join up outside the Synagogue for orders.

"I ignored it," Harry says. "A few minutes later my mother asked if I'd heard what he'd said and to get ready and go out. I said I wasn't going - it was the first time I had a very strong argument with my mother. She was adamant, she actually picked me up and pushed me out.

"That was one of the really most terrible days for me. I started crying. The only thing she said, 'Hopefully one of us will survive.'"

Years later Harry discovered his mother, father and younger sister were sent to Treblinka - an extermination camp. His family are believed to have died in a gas chamber there.

Stephen remembers visiting the site a few years ago with Harry but there were no signs Treblinka camp existed.

"All that was there was a collection of rocks with each rock representing a town from where people were exterminated from."

Camp life

Harry believes his survival was down to luck. He was brought to a number of concentration camps including Rehmsdorf and Theresienstadt.

"On a daily basis, whenever I'd go in the wash room you always had bodies on the floor. Very often, I saw a body laying on the floor who didn't finish their ration of bread. I felt it was my lucky day - I got hold of [the bread] and ate it.

"I never felt ashamed of it or sorry for the guy that was dead. This was on a daily basis and it was really bad."

Speaking to his grandson, and to Newsbeat, Harry says a lot of people would die each day from starvation.

"In every camp you worked very hard, you had to in order to survive."

Stephen asks his grandfather if he hated the Germans for what they were doing to him.

"I didn't hate the Germans," Harry replies. "I came to a conclusion many years ago - if you hate a person or a nation, you live with hate. You can't be a happy and satisfied person".

Death March

Towards the end of the war Harry went on what is known as a 'death march' from Rehmsdorf camp to Theresienstadt.

"They got hold of us all and we had to start walking," he says.

The German soldiers, with their Jewish prisoners, were trying to outrun the Russians, who were trying to free the Jewish captives.

"Sometimes you got a potato and a coffee or something hot and you'd start marching. People on that march died purely and simply from starvation or being shot."

German soldiers killed people who were too slow to keep up with the march.

"We arrived with 270 of us out of 3,000, the rest were killed or had died. It must have been just outside the camp, I remember my head going around and I fainted and I don't remember at all what happened to me."

Harry had survived the Jewish ghetto, the concentration camps and the death march.

Liberation

"I know we were liberated and I was in a hospital and a friend of mine came looking for me. he said, 'Come on let's go out and play in a square, the Russians have liberated us.'

"The first thing I did with my friend, we went to the gate of the concentration camp and we said to the Russians outside that we'd like to go into town.

"He said we'd notice a lot of captured Germans that were being marched to wherever and he [gave us] permission to do whatever to the Germans for 24 hours."

Harry didn't want revenge on the people who had made his life, as he calls it "hell on earth".

Instead he says: "The only thing I was interested in, and so was my friend, was to stop the Germans, open their rucksack and take out whatever was edible.

"I took out only the chocolate."

Stephen's story

Newsbeat asked Stephen how he felt hearing his grandfather talk so openly about the Holocaust.

"I think it's very, very important for him to talk [about the Holocaust]. He's only started doing it the past few years.

"Me and my family are so happy to hear him tell us this because it's something we need to know.

"It's something we can pass down and teach to others so that their memories will stay and hopefully we will never forget".

Stephen says it's important people learn about the Holocaust and praises the Holocaust Educational Trust for taking students to see concentration camps.

Remembering his visit to Poland with his grandfather, Stephen says: "It was always [just my grandfather's] mother, but I left thinking it's not just [his] mother. She was my great-grandmother".

This article was first published in 2015.

Related Topics

- Published27 January 2021