Art archaeology: X-rays & the hidden Rembrandt

11 October 2014

A newly restored Rembrandt will go on show this week harbouring a little-known surprise, a full-scale portrait by the Dutch master hidden from the viewer.

Conservationists have spent the last three and half years restoring Portrait of Frederick Rihel on Horseback, a life-size depiction of a nobleman from Amsterdam and his steed painted in the early 1660s towards the end of the painter's turbulent life.

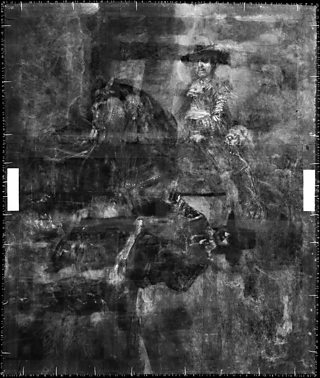

But it is what lies beneath the imposing image that has also excited curators. X-ray imagery has revealed another detailed portrait at right angles to the finished work, unseen underneath the picture on view.

While the painstaking work of repairing the damaged oil painting has been ongoing, scientists and art historians have been playing detective piecing together information on the composition Rembrandt abandoned.

The surprising discovery of the concealed work was made in 2008 but this is the first time in centuries the public will be able to see the finished painting almost as Rembrandt intended thanks to the comprehensive clean-up.

Hidden Rembrandt: Larry Keith explores a work hidden under a Rembrandt masterpiece

Larry Keith is Head of Conservation and Keeper at the National Gallery

It was not unusual for the Dutch artist to re-use a canvas for his self-portraits but the fact this was done on an important commission such as this one has puzzled historians.

Rembrandt did reuse canvases a lot for self-portraits but for an image like this, a commission of large scale work, it seems to be uniqueLarry Keith, Head of Conservation and Keeper, National Gallery

"We just can't be sure why Rembrandt abandoned the portrait, it might be that he was influenced by another picture he saw or the patron may have suggested a change," said Larry Keith, head of conservation and keeper for the National Gallery in London where the painting will go on display as part of its new exhibition examining the painter's late works.

"Rembrandt did reuse canvases a lot for self-portraits but for an image like this, a commission of large scale work, it seems to be unique," he said.

Rembrandt is considered one of the most influential and inventive artists of the Dutch golden age, specialising not only in painting but being a printmaker and draughtsman too.

He was critically and financially successful as a young man, but by the time this work was painted he had endured numerous personal tragedies.

Having already suffered the early loss of his wife and three of their children, Rembrandt's later years were burdened with acrimonious legal proceedings with a former lover, and the loss of his common-law wife and only remaining son. He had been forced to declare himself bankrupt, possibly a clue as to why the canvas was second-hand.

The question now is who was the man in the painting, and could it be a discarded original depiction of Frederick Rihel, a prosperous merchant who is the subject of the finished painting?

"It's broadly similar kind of shape of head but it's not as finished so it's hard to be sure", Larry Keith said.

The mystery man, who appears to have a moustache and goatee similar to Rihel's, is holding what looks like a staff in his right hand and wearing riding costume including a thigh-length coat and full knee-length breeches, according to a study by Marjorie Wieseman in 2010.

The imposing picture, Rembrandt's only equestrian portrait, has been owned by the National Gallery since 1960. It depicts the businessman, an official of the civic guard, taking part in the procession which welcomed the Prince of Orange into Amsterdam in 1660.

Glimpses of the procession can be seen behind the horseman who is carrying a sword and pistol and wearing a buff jerkin with sleeves and cuffs decorated with gold thread.

The decision to clean the painting was made to rectify previous varnishes and retouches which were obscuring the image, and the existence of the hidden portrait was also a question too good to leave unanswered.

Surprisingly, Rembrandt did not put a layer, or primer, between the two portraits, making the oil paint more transparent on the unusually large painting.

"We can understand through working with the scientific department the kinds of changes and pigments that occurred on the picture and how that affects the relationship and the way you read the painting," Keith said.

"So there’s a great deal of new knowledge that comes out as a sort of corollary of doing the restoration treatment itself."

This is not the end in terms of scientific discovery around Portrait of Frederick Rihel on Horseback.

Larry Keith said: "We may one day be able to map the different pigments and produce an even clearer, more precise image of the painting underneath and discover just how finished it was. Watch this space."

Rembrandt: The Late Works opens at the National Gallery on Wednesday 15 October and runs until January.

Rembrandt: The Late Works

A selection of paintings from the exhibition at the National Gallery, which runs from 15 October until 18 January, 2015.

Rembrandt on BBC Arts

-

![]()

Hidden Rembrandt

Art Archeology: exploring what lies beneath the surface of a Rembrandt masterpiece using X-rays

-

![]()

Five Rembrandts

Artist and sculptor Maggi Hambling selects her five favourite paintings by the Dutch master

-

![]()

The Night Watch

What makes The Night Watch so iconic, and did Rembrandt's most famous painting end his career?

-

![]()

Art UK

Browse 112 paintings by Rembrandt in the Your Paintings collection

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work