Matthew Boulton: The grandfather of modern coinage

- Published

In 18th Century England, coin counterfeiting was rife until an entrepreneur dubbed the Richard Branson of his day harnessed the new technology of steam power. Now every coin in circulation can be regarded as the "great-grandson" of those created in a Birmingham factory.

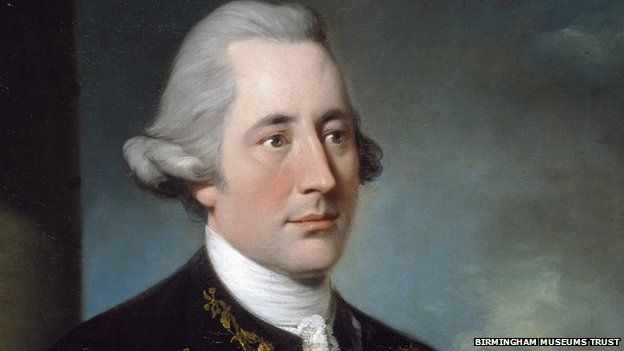

In the late 1700s the town of Birmingham was at the centre of the industrial revolution and the entrepreneur Matthew Boulton one of its driving forces.

A snappy dresser and visionary businessman, his partnership with James Watt saw the latter's steam engine utilised to power machinery while his Soho Manufactory was the largest industrial complex in the world.

But while Britain's industrial technology was leading the world, its currency was unsophisticated and failing to keep pace. Copper coins were in short supply and counterfeiting was rampant.

Dr Kevin Clancy, director of the Royal Mint Museum, said distribution problems of copper coins and the prevalence of fakes meant employers found it very hard to pay their workers.

The Royal Mint had stopped making copper coins in 1775 because they were not distributed beyond London and traders believed there were too many in circulation.

However the industrial revolution was taking off in the Midlands and North and workers needed to be paid in small change - ha'pennies were driving the working man's economy but were in short supply so, inevitably, counterfeiters stepped in.

"People didn't know what was genuine," he says. "You needed an expert to make the fake coins but... the authorities were making it easier for that [counterfeiting] to happen, shall we say.

"Boulton saw the problems and enhanced coin-making."

The main issue was the machinery used by the Royal Mint to make coins. This needed four workmen to operate it which invariably meant each coin was struck slightly differently, some better than others and not all perfectly round, which made it easier for forgers.

Boulton spotted an opportunity to literally make money and set up his own mint in 1789. It replaced the workmen with steam power, producing a machine which struck coins perfectly each time, producing a regular coinage.

Who was Matthew Boulton?

- 1728 - born in Birmingham

- 1762-4 - builds Soho Manufactory and exports jewellery silver decorative wares throughout Europe

- 1766 - helps found the Lunar Society of Birmingham industrialists and intellectuals with Dr Erasmus Darwin

- 1773 - succeeds in a campaign to establish a Birmingham Assay office for the assessing of silver

- 1775 - enters into partnership with James Watt, inventor of the steam engine

- 1789 - establishes the Soho Mint

- 1797 - awarded contract by government to strike copper coinage at Soho Mint

- 1809 - dies at Soho House, Birmingham

To further frustrate the fraudsters he also added a design he thought would be very difficult to copy - a large, raised rim around the edge which prompted them to be nicknamed Cartwheels.

In a notebook from 1789, Boulton wrote: "It will coin faster with greater ease, with fewer persons, less expence and more beautyfull than any coining machine ever made.

"It strikes each piece quite round, all of equal Diameter and exactly concentrick with the Edge which cannot be done quick by any other Machine ever used."

The new technology brought new levels of accuracy, forever changing the way in which coins were made, not just in England, but around the world.

Whereas distribution was once a problem with the Royal Mint, Boulton addressed that by shipping coins to customers.

The Soho Mint produced 10s of millions of Cartwheel pennies within its first 18 months. His machines were also bought by mints in Denmark and Russia in 1797.

Dr Symons, curator of archaeology and numismatics at Birmingham Museums Trust, said Boulton had expected to get a copper coinage contract from the government - "it's like Richard Branson doing the same now" - but he was forced to wait nine years until the authorities relented.

In the early 19th Century, the Royal Mint bought steam engines and coin presses from Boulton, ending the minting of British coins in Birmingham.

"A lot of people wanted to reform what was going on but I think Boulton was the one who came up with the clever idea of how to do it and obviously it worked because every coin used in the world today is made using essentially the system Matthew Boulton pioneered," Dr Symons says.

"We don't use steam engines any more, but they are externally powered coin presses, so you could almost say that every coin used in the world now is the grandson or great-grandson of what Matthew Boulton produced here in Birmingham.

"Mints around the world have always tried to stay ahead of forgers... so there have been changes since Boulton's day, but I think he was the last major individual who had a big impact. I don't think anyone since then has changed coinage in the way he did."

In recognition of Boulton's achievements, a memorial to him was being unveiled at Westminster Abbey on Friday alongside an existing memorial to James Watt. While Boulton was not the first person to tackle counterfeiting, he was arguably the most successful.

"He thought he could do better than what was around, that was true, he moved technology forward, no doubt," says Dr Clancy.

"He was an industrialist, an entrepreneur, he had the means and access to copper and needed an outlet.

"The Mint is into making symbols of trust and that was what Matthew Boulton was doing too - the principles remain the same across the last two centuries."

- Published19 March 2014

- Published1 March 2011