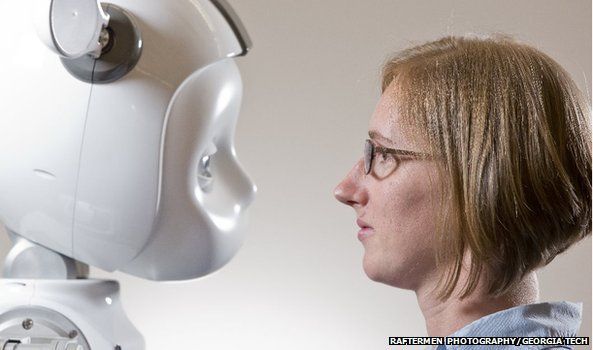

Could robots become too cute for comfort?

- Published

Would you share your innermost secret with a robot? And if you did, would you be comfortable knowing that the secret might be stored online in the "cloud"?

Think of an elderly grandmother with dementia who becomes very attached to her robotic "pet" and you will realise that this isn't science fiction.

There are robots now being tested as teaching aids in small-scale studies with pre-school children, robots helping with the socialisation of people with autism, robots acting as companion pets in old people's homes.

Many of these machines have microphones, cameras, sensors, and internet connectivity.

While it may be some time before social robots become widespread in areas such as care for elderly and young people, the impact of technical and ethical choices made by today's designers will set standards for decades to come.

That was the message from the Social Robotics session of the BBC's first World Changing Ideas Summit held earlier this week in New York.

To help us interact more closely with social robots, some designers are deliberately opting for certain features.

Big, child-like eyes and highly tactile fur are both proving popular thanks to their proven appeal to deep-seated human emotions.

One new design has a space at the front of its head, which allows a real human face of your choice to be projected on to it.

Then there are robotic seals and baby dinosaurs which are bound to bring out the nurturing instinct in us.

And while in the lab this is all done with the best possible intentions, once some of these robots get out into the market place, it's easy to see the potential for misuse.

We tend to have a much more visceral reaction to physical objects - such as robots and drones - than to other technologies, which may be just as inimical to privacy but are invisible, points out Kate Darling, a research specialist at the MIT Media Lab and Fellow at Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

Some of these less physical technologies are already being used in some countries.

Companies offer remote monitoring tech for elderly people in their homes, for instance, allowing family members to track whether they take medicine at the right time, and so on.

When robots are added into the new technological mix, choices about what data to collect become ever more pressing.

A combination of legislative framework and technical solutions is the way forward, according to Andrea Thomaz, associate professor of interactive computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Her lab already requests detailed permissions from people taking part in experiments but a clear understanding on the part of the roboticist about which data is strictly necessary for a particular design also helps.

For instance, can you use a camera which detects movement rather than recording individual faces?

You shouldn't simply collect all the data you can and only later decide what to do with it: you should only collect what you know you will definitely need, says Prof Thomaz.

Moreover, it is perfectly possible to design many robot functions without having to save any data at all. Or, you can give the user the choice which data, if any, to save.

There is no guarantee that these kinds of safeguards will automatically be built into social robots, even those intended to help care for vulnerable people, young or old.

There are always commercial "predators looking for targets", cautions Belgian software designer Pieter Hintjens, former president of the Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure.

This is compounded by a situation where some modern technologies "have so outpaced our understanding that we are struggling even to define exactly what the issues are", he says, never mind starting to solve them.

Add to this our propensity to make choices in favour of convenience and speed and you can see why the issues surrounding intelligent machines and privacy may require decades of public education not dissimilar to car seatbelts and crash helmet for bikers.

In a recent paper for the Brookings Institution, Heather Knight, a robot designer at Carnegie Mellon University, warned that "robotic designers, and ultimately policymakers, might need to protect users from opportunities for social robots to replace or supplement healthy human contact or, more darkly, retard normal development".

Valid concerns, but listening to the people assembled in New York, who are making tomorrow's social robots, one can't help feeling that the protection may need to be much broader before we feel comfortable with social robots as an integral part of our lives.

To hear more about social robots and see other images, please visit BBC World Service's The Forum webpage.

- Published30 June 2014

- Published16 November 2013

- Published20 March 2013

- Published22 December 2006