Obama promotes anti-heroin strategy in coal country

- Published

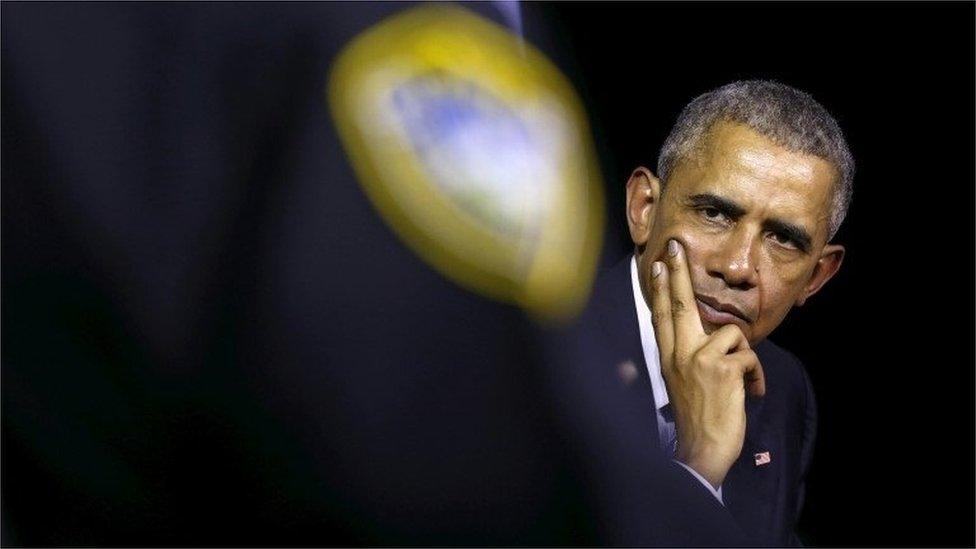

People in West Virginia don't like Barack Obama. But in a state with the nation's highest rate of lethal overdoses, they're ready to try anything - even the president's lefty approach to fighting drugs.

Obama is talking with people in an auditorium at the old Roosevelt Junior High School, which is now a community centre in the Charleston, West Virginia's East End neighbourhood.

He's open-minded about drugs. As he wrote in his 1995 book, Dreams From My Father, he smoked marijuana and tried cocaine when he was in high school.

(He doesn't anymore. When I asked a spokesman, Eric Schultz, on Air Force One whether the president smoked pot in the White House, Schultz gave me a hard stare and said: "No.")

Yet it doesn't take "Freudian analysis", as Jonathan Caulkins of Carnegie Mellon University says, to understand why Obama favours innovative ways to look at the nation's drug problem.

The number of lethal heroin overdoses in the US has nearly tripled in three years, experts write, external, with more than 8,250 people dying every year.

The number of those who've overdosed on prescription drugs has also jumped. About 23,000 people died in 2013, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, twice the number from 2001.

"It's a choice at first, but it becomes an illness" (Video by Colm O'Molloy)

The president no longer has faith in draconian measures once championed by "drug warriors", as Keith Humphreys, a Stanford professor who served as a senior adviser in the Obama White House, describes them.

"There was a mentality for a long time that said: 'They don't need treatment'," Humphreys says. "'They need a kick in the ass'."

Humphreys grew up in West Virginia. A lot of these warriors were living in his home state. Many were in the room with Obama.

The president's visit to West Virginia, a state once known for coal mining and now for heroin, is part of his effort to combat drug abuse and reform the criminal justice system.

He wants to help addicts, not punish them, and has pushed for new sentencing laws for non-violent drug offenders so they don't spend decades behind bars.

He says law enforcement remains part of the effort against drugs. But he says authorities should target "drug kingpins and violent gangs".

Still old habits die hard, and his visit underscores challenges that remain.

In August, White House officials announced they were investing $13.4m (£8.7m) to help states and local governments in the Appalachians, a region that includes West Virginia, learn more about heroin trafficking and its use. Beyond that, the federal government spends billions to fight drug abuse across the country.

Obama also wants to provide training for physicians who prescribe opioids - and wants to see more physicians certified to prescribe buprenorphine, which helps those with addictions.

For these efforts, Obama needs the people in the room.

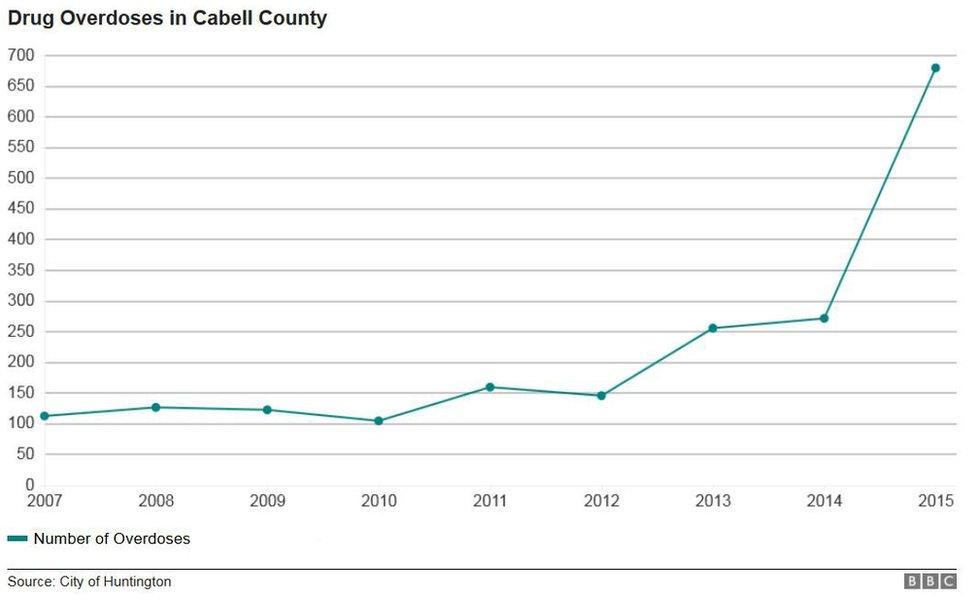

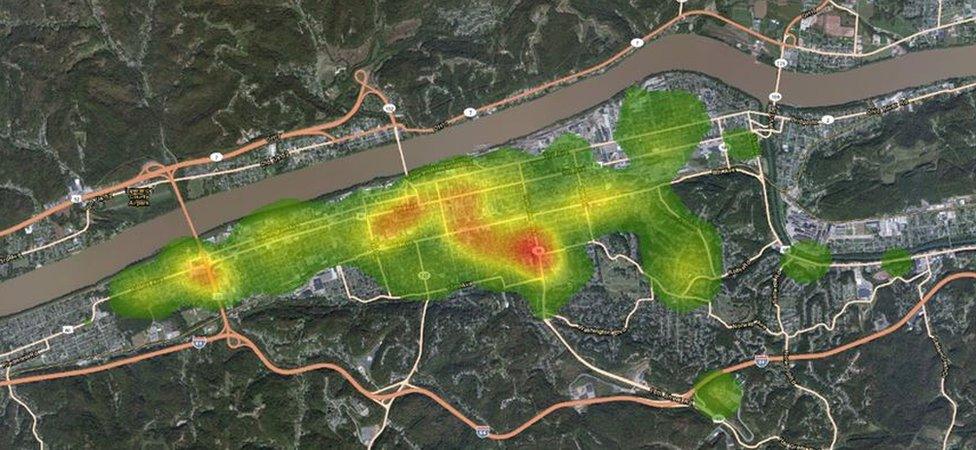

A sharp increase in drug overdoses has been reported in Huntington, West Virginia and in nearby areas

In foreign policy, the president has a lot of control. When it comes to fighting drugs, though, he has to depend on others.

"The president can push," says Peter Reuter, a criminal justice professor at the University of Maryland. "But it's still up to states."

In the US, officials at the state and local level run prisons and police departments and come up with programmes to fight drug abuse.

"This is going to have to be everybody working together," Obama tells about 250 political leaders, law enforcement officials and healthcare workers who've gathered at the community centre. It's a place that's been hit hard.

He's speaking on a stage in a basketball court in the old school, a limestone-and-brick building on Ruffner Avenue that dates to the 1920s. A hoop is attached to one of the pale-yellow walls. A scoreboard is mounted nearby. The ceiling has missing tiles, and chunks of paint dangle over the room.

In the morning old people come here for exercise class, and children show up later for an after-school programme. Police officers from the city's traffic unit also work here.

The people in the room have over time developed a nuanced view of the problem - and of the president.

Jim Johnson, who works in nearby Huntington as director of the mayor's office on drug policy, is sitting in the fourth row. He admits the president is an unlikely hero.

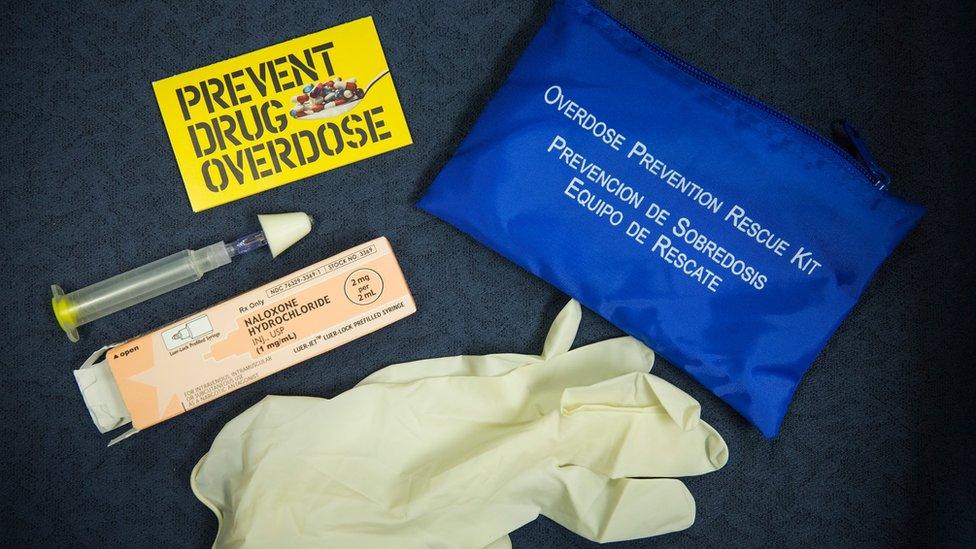

Naloxone is a heroin antidote that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose

"President Obama is not popular in the state of West Virginia," he says. "But this problem is bigger than anything we have ever faced."

For many here the problem isn't political, it's personal. One guest, John Temple, a university professor in West Virginia who has written a book about addiction, American Pain, has seen students fall into the world of prescription drugs.

Obama is sitting next to Michael Botticelli, the director of the White House office of national drug control policy who has been in treatment for alcohol abuse. West Virginia Gov Earl Ray Tomblin's brother was arrested for distributing an illegal drug. Charleston Mayor Danny Jones' 25-year-old son has been arrested for possession of drugs.

"The users are them," Humphreys says. "It shows you this is everywhere."

One speaker, Jordan Coughlen, a student at West Virginia University, says he's on "long-term recovery". His dark hair is neatly slicked back and he's wearing pressed trousers. "Opiates were my lover, my teacher and my best friend," he says.

Afterwards Obama thanks him for speaking out. "Jordan is living proof that when it comes to substance abuse," he says, treatment and recovery are possible.

Clean air initiatives proposed by the Obama administration were unpopular in states like West Virginia and Kentucky, where coal is a big part of the economy.

But change takes time.

After White House officials announced their initiative to look at drug trafficking in the Appalachians, an enlightened effort that emphasises health and safety rather than punitive measures, police officers arrested nearly 100 people in the central part of West Virginia in August.

Known as Operation Mountain Justice, it was "the largest mass arrest of alleged drug offenders in West Virginia history", at least according to local news, external.

The people arrested didn't seem like drug kingpins. Many had been workers in the local mines.

The coal industry has suffered. West Virginia now has one of the nation's highest unemployment rates. "People have nothing to live for," says a physician, Hassan Amjad, who practices 60 miles from Charleston.

Some of his patients have black lung, a deadly respiratory disease that afflicts miners. Others are addicted to drugs. He prescribes an opioid called Suboxone to help.

Amjad tells me people in West Virginia hate Obama because of his environmental policies. They believe his push for climate change regulations have hurt the coal industry and made things harder for them.

(Flying on Air Force One, Schultz acknowledges that things have been tough here. Still as he says: "The decline in coal jobs started well before this president came into office.")

But still they've welcomed him to the event on Wednesday.

Charleston Police Chief Brent Webster is sitting on the stage with the president. Webster is bald and athletic, and he's wearing his blue uniform.

"We basically have a community of zombies for lack of a better word, walking around," he says. The federal money, he says, helps them get addicts into treatment.

Mr Obama is pushing for more doctors to follow medicated treatment for heroin addicts - including buprenorphine

In his heart, though, he's still a police officer - and wants to lock up bad guys. "We can always use additional law enforcement resources - I'm not going to lie to you," he tells the president. Obama laughs.

Other people in the room say they understand. As a former West Virginia police chief, Johnson - now the director of the mayor's office on drug policy office in Huntington - is hardly a progressive, but he's starting to think like one.

He says he doesn't know the details of the mass arrest that took place in August in the central part of the state, for example.

But he knows about one that was done last year, by his former colleagues in the Huntington police department. They picked up a couple hundred people, he said, but many were just addicts. Meanwhile people kept overdosing.

"We came to the realisation that we couldn't arrest our way out of the drug problem," he says.

He says they tracked drugs in their city on a screen with topographical-like makings - "like a weather map". More than a decade ago, drugs were found in small areas around town. Last year they were everywhere.

"It was so dramatic," he says, describing the maps. "It looks like a sunny day in 2004 and like a thunderstorm in 2014."

A heatmap of drug offences in Huntington, West Virginia in 2004...

...and in 2014

He and others have fought drugs in their town for years, and things were only getting worse.

"The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results," he says.

Towards the end of his presentation, Obama says people now have a better understanding of what needs to be done. But it's still hard. "We've got to make sure the money is following the insight," he says.

Obama unclips a microphone and steps down from the stage. He shakes hands with people in the audience and smiles. A John Denver song, Take Me Home, Country Roads, suddenly blares out of loudspeakers.

The mood is festive, a sharp contrast to the sombre moments during the event. But not everybody looks upbeat.

Temple is standing in the back, holding a copy of his book under his arm.

"I think it's amazing that he's here but policy-wise there's more that needs to be done," he says.

"If this were another disease, we'd be pulling out the stops," he says, watching the president at the front of the room.

He knows it's not Obama's fault. But he shakes his head as if to say: it's frustrating.

- Published31 July 2014

- Published20 March 2014

- Published23 July 2014

- Published8 February 2014