Shock tactics: prize brings your writing skills to life

13 January 2016

He is 200 years old this year. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was first brought to life two centuries ago, becoming one of the key Gothic novels of the Romantic period. To mark the anniversary, a new writing competition wants to know what you think happened After Frankenstein. That is the theme of the prize from the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association.

The competition, held annually for essays and poems on Romantic themes, is open to all aspiring writers from 16 upwards and is free to enter. RICHARD HOLMES, the chair of the jury and biographer of Shelley, told Get Creative why two centuries on Frankenstein still has the power to shock.

The fabulous inspiration of Frankenstein by Richard Holmes

It’s still amazing to me that Mary Shelley began the novel in a simple notebook (which still exists in the Bodleian Library, Oxford) when she was only 18-years-old ( in June 1816) and published it when she was just 20 (in March 1818). By the time she returned to England from Italy at the age of 25, the first theatrical version, Presumption! - or the Fate of Frankenstein - had already made her famous. In fact by now, 200 years later, maybe she is even more famous than her husband the poet Percy Shelley.

Her story of Frankenstein and his monstrous Creature has always had a strange power to set people’s imagination on fire. It is the first true science fiction, and the first unforgettable parable about the perils of modern science.

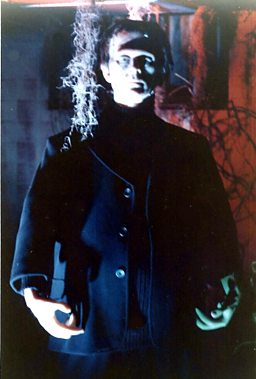

It has been made into more that 100 films: notably with Boris Karloff, in 1931; with Marty Feldman in Young Frankenstein in 1974; and Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1994. There have been over 70 stage dramatizations since the first in 1821, including musical comedies, numerous television adaptations and pop music albums (by Alice Cooper and others). There has been a Frankenstein on ice, and various Frankenstein graphic novels and Frankenstein cartoon serials (The Munsters). Danny Boyle’s stage production of Frankenstein with Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller at the National Theatre was a huge popular hit as recently as 2011. A Frankenstein ballet by Liam Scarlett will open at the Royal Opera House this May 2016.

But don’t let all this put you off. There is room for more inspiration, more fire, your particular fire. My advice to young writers is to forget any thought of a school “text” book or a “classic” work or a horror “B” movie. Start again, start at the beginning, start simple.

Think of 18-year-old Mary scribbling in her notebook (or maybe on her laptop). She is trying out her first, crazy, terrifying adventure story – simply to see where it will lead. Join her! Treat her novel as a recipe book of pungent ideas, a box full of dangerous experiments, a tool kit of fantastic speculations. See which ones you can use. For instance, in your essay you could put yourself in the position of one of her other characters: not just Frankenstein or his Creature, but his friend Clerval, or his fiancée Elizabeth, or even his university teacher Dr Waldman. How would they see the story? Or describe Frankenstein’s laboratory in more detail (not just the Swiss one, but the Scottish one too, “in the remotest of the Orkneys”).

It is the first true science fiction, and the first unforgettable parable about the perils of modern science

What would have happened if his experiment had turned out differently? Or if he had created that second Female Creature? Or if he had treated the Creature more kindly, with more understanding, in the wind-swept confrontation on the icy Mer de Glace? Or during the cruel pursuit to the Arctic? More like a kind of asylum seeker? (And why did Mary use so many frozen scenes of ice and snow in her novel?)

Or imagine the moment in which Mary herself first thinks of her story at the Villa Diodati in 1816, and the nightmare which follows? (Have a look at her “Author’s Introduction” of 1831.) Was she making that up too?

Or stand the story on its head, and consider your favourite scene as comedy, or black farce, or angry satire; or re-write it in a different form as an elegy, or a love poem, or even a single beautiful melancholy sonnet. Or turn it over again, and ask what would a modern twenty-first century Frankenstein be working on? – a huge artificial intelligence, an army of cyberspace men, an all-powerful bionic woman, a race of robots to send to Mars? In your hands, it’s alive, it’s alive!

Deadline for all entries week beginning 1st February 2016. Full details can be found on the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association website.

A fresh look and a fresh listen

Feeling poetic? Here is advice from competition judge Matthew Sweeney on getting lyrical.

I always throw a few quotes from Robert Frost at novice poets. For example, 'Poetry is a fresh look and a fresh listen'. In other words, it's important to strive for freshness, and try to say things in a new way, not in a hackneyed or cliched way that everyone knows already.' Here is Frost further on this: 'Cliches and jaded diction carry no insight because they freeze meaning, allowing the mind no new feats of association; an idea has to be a little new to be at all true, and if you say a thing three times it ceases to be so.'

Another great dead American poet, Elizabeth Bishop, put the same thing another way, when she was complimented by the poet Frank Bidart on the closing lines of a poem - he recalled her response: 'She said that when she was writing it she hardly knew what she was writing, knew the words were right and (at that she lifted her arms as high, straight above her head as she could) felt ten feet tall.'

From the archives

-

![]()

The Strange Affair of Frankenstein

Robert Symes investigates the background to Mary Shelley's novel.