A hunger for romance in northern Nigeria

- Published

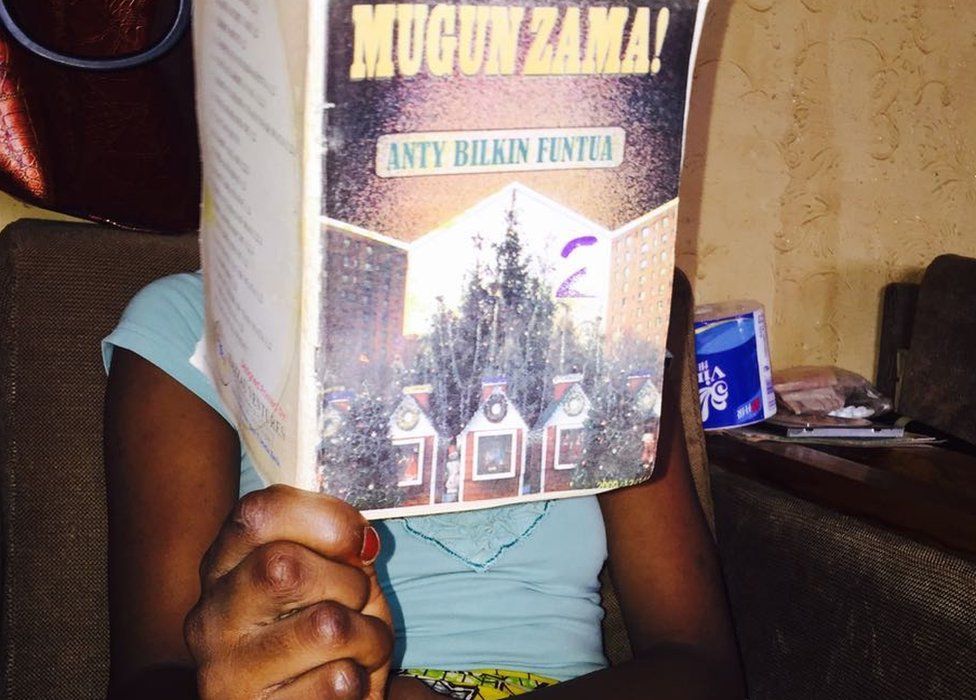

Women and girls in northern Nigeria have a voracious appetite for romantic fiction that is taking on conservative attitudes in this largely Muslim region.

Written in the local Hausa language by women for women, Kano city's equivalent of the Mills and Boons industry, known as "Litattafan Soyayya", is a booming business.

"I read these novels to know how to handle complex life issues, like courtship and what life is in the matrimonial home," says 23-year-old Hadiza Ibrahim Kabuga.

One of the bestsellers, A Daren Farko, meaning "On the First Night", is especially popular with girls and young women about to be married - detailing what they can expect on their first night in the marriage bed.

The novels are a way for women to talk about issues not openly discussed in northern Nigeria.

Girls are often treated differently from boys, with some parents believing they do not need an education as their early years are just a preparation for marriage.

Polygamous problems

"In my writing I give more attention to women's issues, like marriage, polygamy and education," says Fauziyyah B Suleiman, who has written 32 novels and makes enough money to live by her writing.

Three of them have proved so successful that they have been turned into locally produced movies.

One called Rumaysah deals with polygamy and the complications that come with it.

Rumaysah is a woman driven by jealousy who is determined to stop her husband from taking a second wife and ends up murdering him.

The trickery and subterfuge of life in a polygamous family is also raised by many of the novels.

Others will, for example, chronicle the rise of an illiterate child bride who rebels against her family to get an education - ending with her becoming aware of her rights within and outside the family.

"Such novels bring to the fore the much-needed change in the way women are treated in Hausa society," says literary critic Murtala Abdullahi.

It allows women not only to express themselves but be viewed in a different light, he adds.

"Hausa romance novels often present the image of women not only as housewives and mothers, but also as breadwinners or political activists or professionals."

The novels sell for about 300 naira ($1.50, £1) each and can be bought at book stalls in all markets.

"Every week at least five new novels come on to the market - some selling in their thousands," says Ali Mai Litattafai, who runs a bookshop in old Kano city.

"In the past people had the wrong impression of issues such novels raise, but now people have realised that they are for the good of the society."

At one of the shops I met a boy who came to pick up the latest novels for his mother - some women here stay at home as they are not allowed to mix with men in public.

Most of Mr Litattafai's customers are married women, some of whom buy in bulk and then loan out copies of the romances in their neighbourhoods for a small fee.

It is usually about $0.70 to borrow three books for a week.

Book burning

The novels are also serialised on the radio.

When Express FM in Kano airs its romance novel slot at 09:00 every weekday morning, many homes comes to a standstill for the next 30 minutes.

It can also be heard outside the city in rural areas, where literacy is lower. Kano State as a whole has female literacy rates of between 35% and 50% - in much of the rest of northern Nigeria it is lower than 35%.

Some teachers have complained that the books interfere with girls' concentration at school.

"I used to have to frequently confiscate the romances when I caught students secretly reading them on their laps," says Naziru Mikailu, a BBC journalist who used to teach at a school in Kano.

Some Islamic scholars have had more of an issue with what they consider the vulgar and erotic content of the novels.

The Kano governor in 2007 led a widely publicised burning of thousands of the novels.

A censorship board was then set up, requiring writers to present their works for scrutiny before publication.

This has now been relaxed after some writers won a civil court case which upheld their freedom of expression.

But the Hisbah religious police - who are tasked with upholding Islamic law - are still touchy about them.

In February, they stopped a popular narrator of the novels, Isa Ahmed Koko, from visiting Kano to meet his adoring fans.

This was in response to a Facebook campaign set up by men upset by the prospect.

"Many married women will abandon their homes and tell their husbands they are maybe going to the hospital only to end up at the meeting," one of them posted.

Mobile phone feedback

The authors often put their mobile numbers on the cover of their novels, allowing direct feedback from readers who sometimes get in touch to offer them gifts.

But some have received threatening messages, urging them to stop writing.

Maryam Salisu Maidala, a teacher who has written two romance bestsellers, says she has never been on the receiving end of a threatening call, except from fans urging her to hurry up with a sequel to her popular book Kainuwa.

"I reflect reality to the extent that sometimes readers call my mobile to ask me if my novels were based on real life stories that had happened."

She writes her novels by long hand, because of Nigeria's erratic electricity supply, and says that the serialisation of her books on the radio has helped boost sales.

Social media, on the other hand, is posing a problem for the writers as groups have been formed on Facebook or WhatsApp where whole novels are uploaded.

"Social media is gradually eroding readership of Hausa novels because people can now share electronic copies of a novel. This affects our sales," says Ms Suleiman.

But it is not an ideal reading experience, so for the moment Kano's literature of romance looks secure.

"After school I read such novels in my free time. We girls don't get out of our homes much - so it's my way of relaxing," says 18-year-old Sadiya Hussaini, who like the other romance fans did not want her photo taken.

"Many of the stories teach you how to handle boys - and I learn how complicated life is.

"The suspense also keeps me excited, gives me something to look forward to."

- Published19 February 2016

- Published29 May 2014

- Published25 February 2015

- Published21 March 2015