Gerda Taro: The forgotten photojournalist killed in action

- Published

In July 1937 a Jewish emigre from Nazi Germany became the first female war photographer to die on assignment. At the age of 26, Gerda Taro was just starting to make a name for herself and had already helped launch the career of the young Robert Capa.

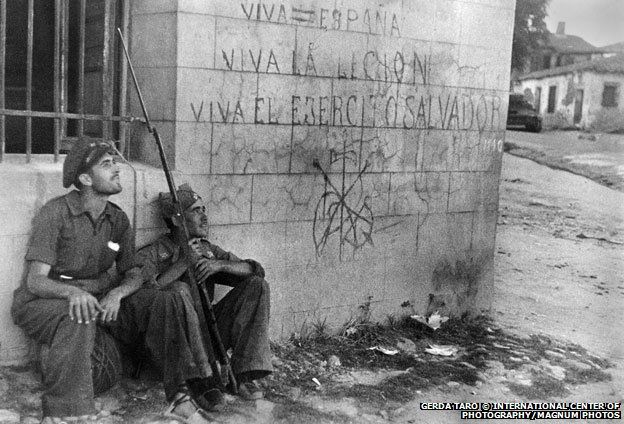

Gerda Taro spent the last day of her life in the trenches of Brunete, west of Madrid, holed up with Republican fighters.

It was a critical moment in the Spanish Civil War - Gen Franco's forces had just retaken the town, inflicting heavy losses on the Republicans' best troops, who were now under fire as they retreated.

As bombs fell and planes strafed the ground with machine-gun fire, Taro kept taking photographs.

She was due to return to France the next day and only left the trenches when she ran out of film, making her way to a nearby town.

"She was elated, saying 'I've got these fantastic photographs, I've got champagne, we're going to have a party,'" says Jane Rogoyska, author of a new book, Gerda Taro, Inventing Robert Capa.

She jumped onto the running boards of a car transporting wounded soldiers, but it collided with an out-of-control tank and she was crushed. She died in hospital from her injuries early the following morning.

Her photographs from that day, 25 July 1937, were never found.

She had spent the previous year making regular trips to Spain to document the fighting.

"Taro became very emotionally involved in the Spanish Civil War… she was so passionate about the suffering of the Spanish people," says Rogoyska.

Republican fighters had great respect for her. In her book, Rogoyska quotes the memoirs of Alexander Szurek, an adjutant to a Republican general: "We all loved Gerda very much… Gerda was petite with the charm and beauty of a child. This little girl was brave and the Division admired her for that," he wrote.

On some previous trips, Taro had been accompanied by her partner, photographer Robert Capa, but on this occasion she travelled without him and fell in with Canadian photographer Ted Allan.

Keen to prove herself and get the most dramatic pictures she could, Taro started to put herself in increasingly dangerous situations.

Capa never forgave himself for letting her go without him, though he himself subsequently became known for the saying: "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough."

"He blamed himself for not being there - he always felt that he had this role of a protector towards her because he felt that she would take too many risks," says Rogoyska.

He also felt responsible because he had introduced Taro to photography.

The two Jewish emigres had met in Paris three years earlier.

She was Gerda Pohorylle, recently arrived from Leipzig, and he was Andre Friedmann - a handsome, disorganised young photographer from Hungary.

Both had fled from persecution and were struggling to get work.

"Their meeting somehow set off a wonderful combination of talents," says Rogoyska. "He taught her photography and she taught him how to make the best of himself."

It was hard for foreign photographers to get their pictures into the French press, she says. "They came up with this crazy idea of inventing a very successful, wealthy American photographer who had never been to Europe." He had only recently arrived, the couple explained, which is why no-one in Paris had heard of him.

"He was going to have this name that sounded a little bit sort of international and glamorous, so they called him Robert Capa," Rogoyska says.

The plan worked. Friedmann operated under the name Robert Capa and started to get noticed. Taro also took her new name at this time.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, the couple seized the chance to raise their professional profiles and, simultaneously, to take part in the struggle against fascism.

Two weeks after fighting began, the couple arrived in Barcelona where they photographed Republican soldiers preparing to go to the front.

They went on to travel hundreds of kilometres through Republican territory to Aragon, Madrid and Toledo and then south to the front-line near Cordoba.

Their work was well received back in Paris, where newspapers were keen to publish photographs that would support the Republican cause.

Taro started to develop her own style and managed to carve out this career, establishing herself as a photographer in a very brief space of time, says Rogoyska.

Today, Capa's name is internationally recognised, but until recently Taro was largely forgotten.

"Given the historical circumstances it's not really surprising that Gerda's achievements faded," says Kate Brooks, an American photojournalist who has worked in conflict zones in Afghanistan and Iraq.

She puts it down to "the fact of World War Two, because of the fact that her family died in the Holocaust and that basically with Capa's death [in 1954] no-one was left to preserve the memory of her work."

Brooks only became aware of Taro a few years ago, after 4,500 negatives belonging to Capa, Taro and fellow photographer Chim, turned up in Mexico.

Capa tried, and failed, to smuggle the pictures out of France in 1939 - instead they ended up with the Mexican ambassador, Gen Francisco Aguilar Gonzales, who eventually took them home and forgot about them.

The negatives sat in boxes in Mexico, untouched for half a century. After Gen Aguilar and his wife died, the photographs were passed on to a relative, Mexican filmmaker Benjamin Tarver.

When Tarver realised what he had inherited, he told a professor in New York, who in turn got in touch with the city's International Center of Photography (ICP) - founded by Capa's brother, Cornell.

Cornell Capa felt the pictures belonged with the rest of the Capa and Taro archives but Tarver failed to answer his letters.

That was in 1995, and it wasn't until 2007 that negotiations finally took place resulting in Tarver giving what had become known as the Mexican Suitcase to the ICP.

Three years later the organisation put on an exhibition of the long lost photographs.

"Anyone who is covering war at any point in time is basically putting their life at risk by getting close to what's happening," says Brooks, but she can understand what motivated Taro.

"The purpose in doing photography, and or filmmaking, is in documenting and having a record of what is happening," she says.

"I think it's really quite tragic that beyond dying so young, we didn't have an opportunity to see how her work as a photographer would develop."

Jane Rogoyska and Kate Brooks spoke to Newshour on the BBC World Service.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook

On a tablet? Read 10 of the best Magazine stories from 2013 here