Five Seismic Moments in New Music

The story of new music is peppered with events that have altered the course of musical history. In Radio 3's 2016 New Year New Music season, we asked five presenters each to tell the story of one of these 'seismic moments'. From silence and ambient sounds to riot and revolution, these intriguing events have, in different ways, changed the progress of sound and culture – or, as one of our five suggests, have they?

John Cage: 4'33"

John Cage: 4'33"

Robert Worby reflects on the first performance of John Cage's 4'33".

Robert Worby's selected seismic moment in new music is the first performance of John Cage's controversial 4'33" and its impact on performers and audiences ever since. Notorious as the piano piece in which no actual music is played for four-and-a-half minutes, to non-musicians ‘Four-thirty-three’ is seen as a benchmark of avant-garde eccentricity. But anyone who has actually heard a performance – as opposed to hearing about a performance – would concur with Cage that his critics missed the point. ‘There's no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence, because they didn’t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds. You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.’ Robert Worby, who has performed the work, reveals how Cage was struck by a visit to an anechoic (completely soundproof) chamber at Harvard University; after his session, he remarked to the engineer that he could actually hear two sounds, a high one and a low one. ‘He informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation.’ Robert also explains how 4'33" was premiered at a time of heightened tension in US national and sexual politics.

Music after the Wall came down...

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

Sara Mohr-Pietsch on the appetite in the west for eastern European music after 1989.

Sara Mohr-Pietsch's chosen seismic moment in new music looks to the fall of the Berlin Wall. She reflects on the accompanying rise in the popularity of Eastern European composers as a simplicity in musical language emerged from behind the Iron Curtain. The music of Pärt, Gorecki and Kancheli came to the fore: it achieved almost instant popularity because it offered artistic continuity, in a way which the avant garde, which breaks with convention and values newness and originality, didn't. Instead, the music was rooted in ancient sacred music, connecting back to plainsong and also to the Baroque and Classical eras. Having lived through two world wars and suffered the effects of fascism and totalitarianism, these composers arrived at their music language through decades of artistic soul-searching in challenging artistic times. In the end the fall of the Berlin Wall didn't give way to a revolution in composition, but unexpectedly led to a revolution in listening.

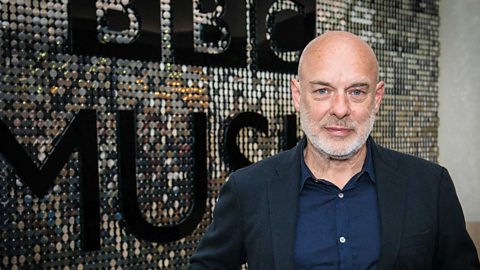

Brian Eno: Music for Airports

Brian Eno's Music for Airports

Ivan Hewett reflects on Brian Eno's creation of a new genre which he named ambient music.

Brian Eno (b. 1948) came to music through visual art; early in his career he was a member of Roxy Music, and after leaving the band, where he had graduated from audio mixing to synthesiser playing onstage, he launched a solo career working in various branches of experimental music. In his 1978 album Music for Airports, Brian Eno created a new genre of music he named 'ambient music'. The album was designed to ease the tedium of waiting in airports, but ambient music, which Eno said was 'as ignorable as it is interesting', had an influence way beyond that. Ivan Hewett looks into the genesis and subsequent history of ambient music, and explains why Eno's description is not as self-contradictory as it appears to be.

Steve Reich: Four Organs

Steve Reich's Four Organs

Sarah Walker reflects on Steve Reich's radically minimalist Four Organs.

Sarah Walker's chosen seismic moment in new music describes the notorious 1973 concert when Carnegie Hall played host to the radically minimalist Four Organs by Steve Reich. At its premiere in New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 1970, the work had been well received, with subsequent performances elsewhere in the US and in Europe greeted with, at the very least, respect, and at most, genuine enthusiasm. But in the conservative mainstream venue of Boston Symphony Hall in 1971, Four Organs was met with ‘loud cheers, boos and whistles’; and at Carnegie Hall, one of the performers Michael Tilson Thomas, remembered that ‘One woman walked down the aisle and repeatedly banged her head on the front of the stage, wailing “Stop, stop, I confess”.’ In her Essay, Sarah Walker also looks at how minimalism, together with the idea of the composer-performer ensemble, changed the history of 20th century music.

Tom Service: Where have all the seismic moments gone?

Tom Service: Where have all the seismic moments gone?

Tom Service reflects on the lack of any seismic shocks in 21st-century music.

Tom Service explores musical creativity and seismic shock in the twenty-first century. By the time the 20th century was 16 years old, music like Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, Strauss's Salome, and Schoenberg's Five Orchestral Pieces had sent shockwaves through the tectonic plates of musical and cultural convention. In ripping up the musical rule-book, these pieces were heard to threaten social and even moral stability as well. So where are the seismic moments of the first 16 years of the 21st century? Why haven't composers been able to write another Rite? Is it because new music has lost its cultural capital? Or is it, rather, that seismic activity is happening even more today than it was in 1916– an endless series of mini-earthquakes rather than a single musical volcano, biding its time until all that creative energy breaks through?