The results of an international trial show stem cell transplants can vastly improve the lives of some people with multiple sclerosis.

The gruelling treatment involves wiping out a patient's faulty immune system with drugs used to treat cancer - and then rebuilding it using stem cell transplants.

The BBC's Caroline Wyatt, who was deemed unsuitable for a trial in the UK, paid for a stem cell transplant in Mexico.

How my MS took hold

Early one evening, the world around me began to spin uncontrollably.

My brain froze as the dizziness took hold. My legs gave way and I collapsed on to a friend's living room floor.

It was late in 2002 and this was the start of my long, slow path to a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and, finally last year, a stem cell transplant.

I had spent that week in 2002 filming Siberian tigers in the far east of Russia. We had just flown back through eight time zones to Moscow when I collapsed.

A brain scan showed a lesion on the right side of my brain. It wasn't clear exactly what that meant. The neurologist told me that while it might be an early sign of MS, it could equally well be nothing to worry about.

“Do come back if you find that you can't walk,” he said with a polite smile as he showed me out.

Because I looked so well, it took another 13 years before I was definitively diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS in late 2015.

Yet I'd known something was badly wrong when the very first symptoms appeared in 1992, and my arms and hands became so weak and numb that I couldn't type, wash my hair, or even lift a kettle.

That was diagnosed as repetitive strain injury, and it improved after several months of rest. But it never really went away, and the fatigue that came with it got worse with every year.

Later on, I was told that my constant tiredness was chronic fatigue syndrome, which is also known as ME.

The early symptoms of multiple sclerosis are often so similar to many other diseases that it's not unusual to have a lengthy period between the onset of the illness and a definitive diagnosis.

By 2015, the symptoms were unmistakable.

When I went numb down much of my body for several weeks, I was given another brain scan and finally diagnosed with MS.

The neurologist put me on a drug called Tecfidera, which was aimed at modifying the course of the disease.

But the tablets didn't work for me. Not long after starting them, I collapsed again - this time in the street - and woke up the next day with double vision.

For several months afterwards, I was unable to walk properly and suffered constant dizziness, nerve damage to the eyes and tinnitus.

That relapse also left me with problems with proprioception - the knowledge of where my limbs are in space.

This meant that I knocked over my cup of tea, or the glass by my bedside at night, and bumped into doors and walls with bruising regularity.

This time it was a new lesion on my brain stem that had caused the relapse.

The brain stem is one of the most important parts of the brain - regulating the central nervous system, and controlling essential functions such as breathing, swallowing, heart rate, blood pressure and consciousness.

The after-effects of that relapse were so bad that I had to give up the job I loved as a specialist correspondent for the BBC.

My ability to find words, think and speak clearly, or comprehend and remember material quickly, was - and remains - much diminished.

Thankfully my sense of humour was still intact, as my friends and family made light of the eye patch I wore across one eye to deal with the double vision.

Each eye was still functioning, but the part of the brain that should have correctly interpreted and merged the signals coming in from both eyes was not. I'm still grateful every day that the double vision resolved itself a few months later.

I'd always joked that in order to work in TV news, all you had to be able to do was walk and talk at the same time.

But by mid-2016 I could no longer do that. As I lay awake in bed at night, my arms and legs were so weak that I feared that I would soon need a carer just to help me get dressed in the morning.

When a kindly nurse at the hospital suggested that bladder problems meant I might think about new drugs, or perhaps even a catheter, I decided I had to take action.

At the age of 49, I was not yet ready to accept a level of disability that would take away my independence.

Could I have a stem cell ‘reboot’?

I'd seen a Panorama programme made by my colleague Fergus Walsh in 2016 about medical trials using stem cell transplants for MS.

It showed near-miraculous results for some patients, especially those with relapsing-remitting MS.

The trials in Chicago were led by Dr Richard Burt, with patients taking part at centres around the world.

Many years ago while still in training, Dr Burt noticed that leukaemia patients needed to be re-immunised against common illnesses after their immune system was wiped out by chemotherapy.

He wondered whether it might have the same impact on auto-immune diseases such as MS by destroying the faulty immune system, with its cellular memory of disease, and allowing the body to start again - or ‘reboot’ - from scratch.

It was the beginning of the long journey to his latest randomised trial results.

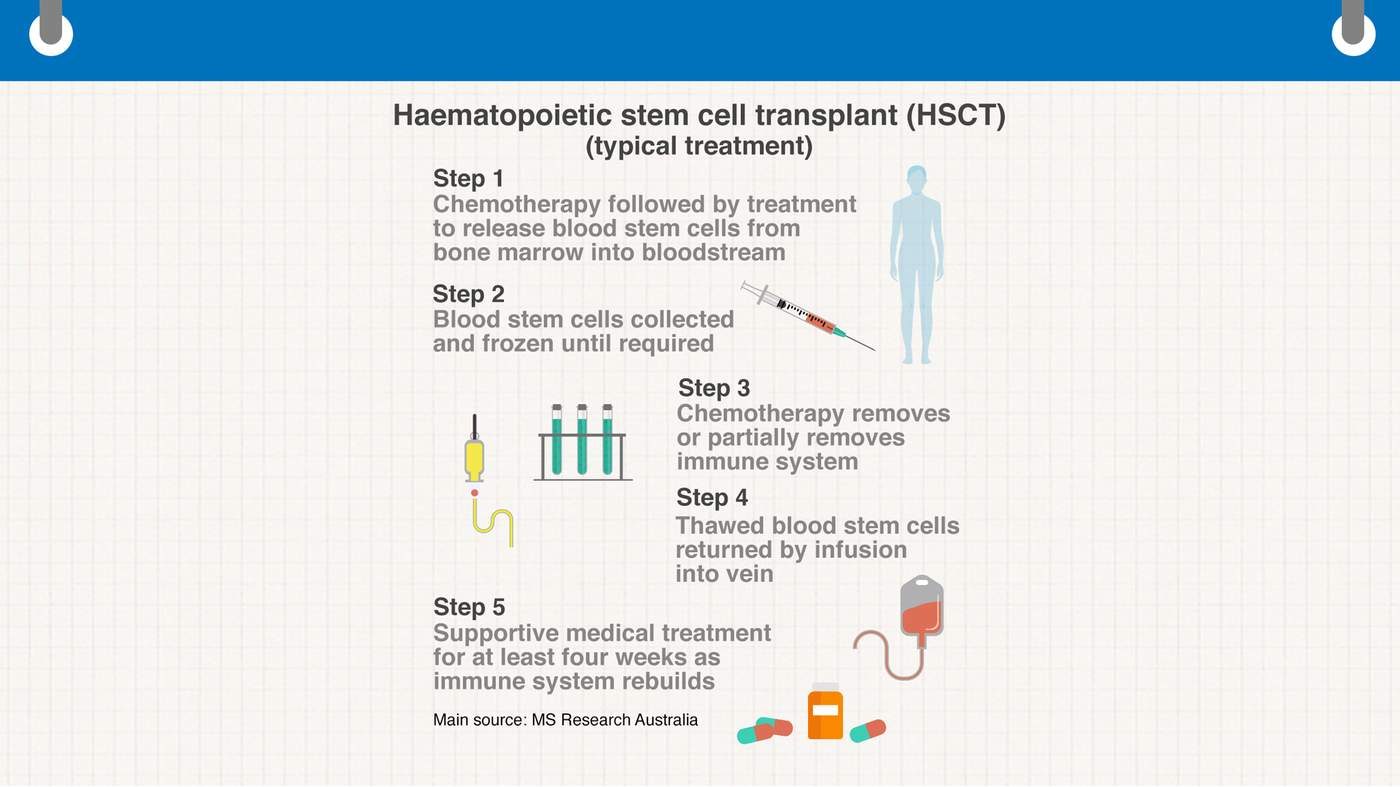

The initial stage of the trial was aimed at showing that MS patients could safely undergo chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant using the patient's own cells - the building blocks of the immune system.

The process is known as a non-myeloablative autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplant, or HSCT for short.

The first such experimental transplants for MS were performed in the mid-1990s in both Greece and America. However, early mortality rates were unacceptably high.

The patients selected were often in the late progressive stages of MS and it was not yet clear what dose of chemotherapy worked best.

But as time went on, the centres around the world that offered HSCT for auto-immune diseases began to work out which drugs were most suitable, and what dose of chemotherapy was sufficient to halt MS - as opposed to cancer - without a too-high risk of death.

After reading as many of the medical papers as I could, I contacted the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield, where neurologist Professor Basil Sharrack and haematologist Dr John Snowden were leading the UK arm of the trial.

They offered to perform the stringent tests that were required to see if I would qualify under the trial's strict criteria for treatment.

I was deeply grateful to the team at Sheffield for agreeing to see me, but devastated when I learned that I didn't qualify.

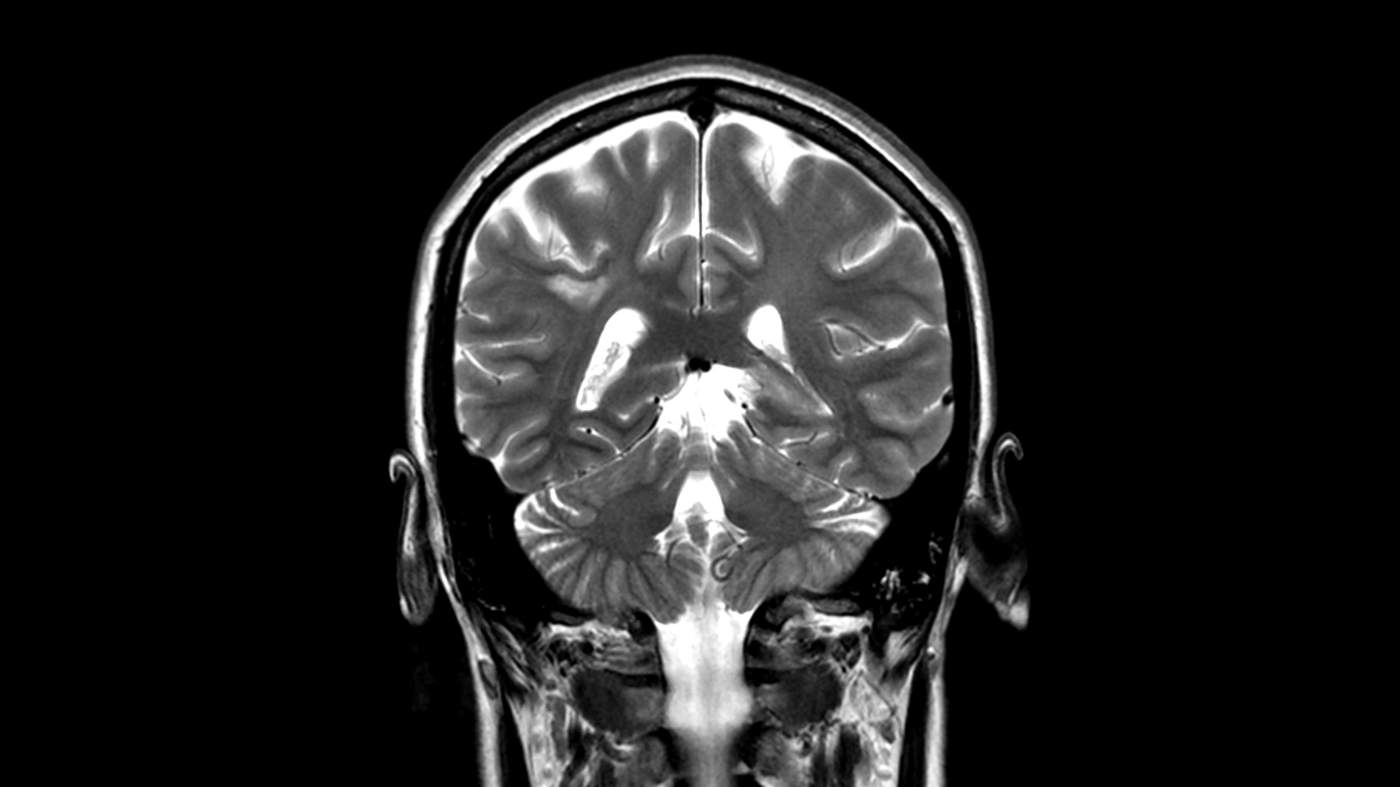

One of the key tests for patients taking part in the trials or having such treatment on the NHS is an MRI brain scan, which the trials state must show active and inflammatory lesions on the brain.

Image from one of Caroline Wyatt's brain scans

My initial scan didn't, suggesting to the team that I wouldn't be a good candidate for a stem cell transplant.

By then I was aware that I might already be on the cusp of moving into secondary progressive MS, when the illness is well-entrenched and the degeneration of the brain can no longer be stopped.

That can mean HSCT may not work as well - or at all - to halt further progression.

My decision to go ahead with HSCT abroad was a tough one, reached after long discussions with my family and friends.

I was aware that there is a small but significant chance of death (well under 1%) from infection or other complications during or after chemotherapy.

That risk is deemed acceptable in more acute illnesses such as cancers that would kill if left untreated.

But many neurologists in the UK remain wary of recommending harsh chemotherapy agents for people with MS, whose illness is considered lifelong and chronic.

Some prefer to take a “wait and see” approach, rather than treating MS early on with the most powerful but expensive drugs that are now available. Those, too, can have serious side-effects.

The multiple sclerosis ‘mice’

No neurologist had been able to explain why I had MS nor what had caused it.

Decades of scientific research have shown that more than 100 genes can play a role, and that environmental factors may combine with a trigger to set off the fault in the system that leads to MS.

Stress often makes symptoms worse.

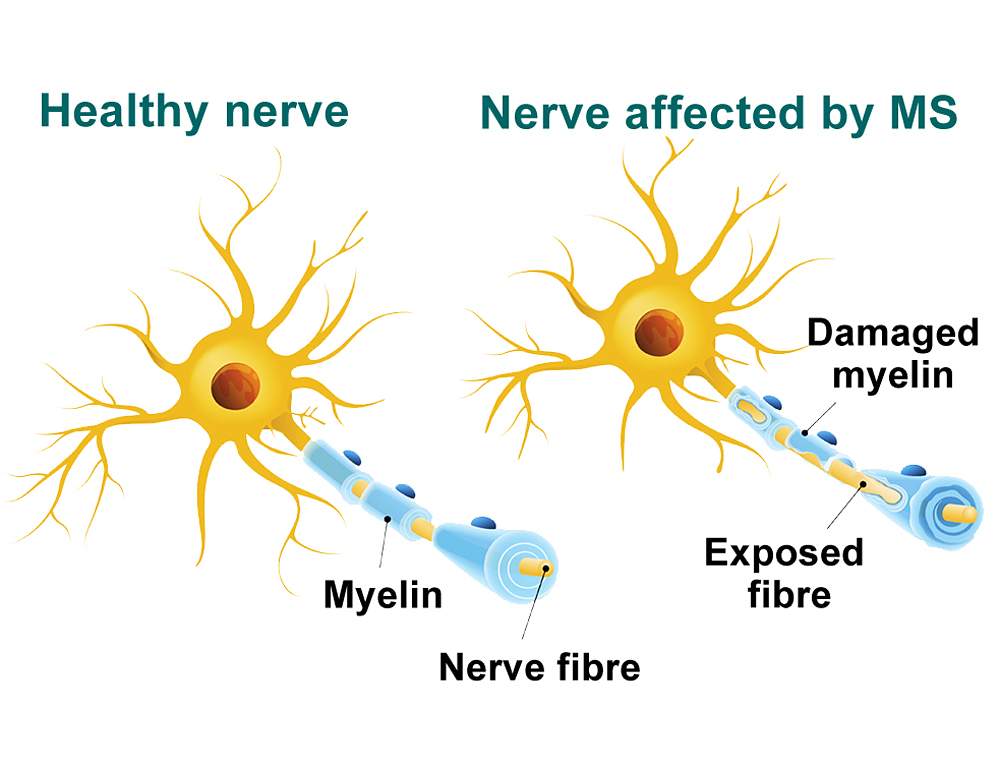

It's thought that MS occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the protective fatty layer of myelin surrounding nerve fibres in the brain and spinal cord, causing scarring or sclerosis.

It's a little like mice nibbling on electrical cables and short-circuiting the electricity supply, making the lights flicker on and off before coming back to life - or leaving you permanently sitting in darkness.

Those with relapsing-remitting MS may have periods of near-normality, as I did, interspersed with damaging relapses associated with inflammation that causes lesions to develop within the brain, spinal cord and optic nerve.

*Figure does not include other drugs, including painkillers. anti-spasticity medication etc...

(NHS England 2016-17)

I was quite happy to undergo chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant if it meant potentially keeping the mice at bay and the lights on for longer, and halting the progression of my MS.

I understood that in HSCT, the chemotherapy was aimed at killing off the malfunctioning immune system before the body reboots and reconstitutes a new one - ideally without the faults of the old one.

One of my main worries ahead of treatment was that there is a period after chemotherapy, called neutropenia, during which other infections can quickly take hold if not prevented. That can even lead to sepsis, which can be deadly if not treated in time.

Yet by the end of 2016, I already felt that the disease itself was killing me - just more slowly than cancer would.

Because I looked (and still do) in the very best of health, it was hard for anyone to comprehend that I really was ill and found it difficult to perform even the simplest tasks at home or at work.

For me, that small chance of death following chemotherapy was infinitely preferable to the certainty of further silent decline.

Day by day, year by year, many people with MS lose a small part of themselves in that daily struggle against constant but invisible neurological fatigue and pain.

Many of us see our hopes and ambitions die, and all too often lose our jobs, marriages and closest relationships.

Living with a partner who's always exhausted - and whose ability to see, speak or walk can vary from day to day - is rarely easy.

Many relationships break up thanks to MS, including my own.

And life expectancy for those with MS is usually reduced by some seven to 10 years.

While disease-modifying drugs may help alter the course of the disease, many of them can also make patients feel worse. This means that quality of life often suffers with or without drugs.

I researched having HSCT for MS elsewhere in the UK after finding out that it is now performed in London by the NHS for patients who qualify, at hospitals including Kings College, Charing Cross and University College Hospital. It is also offered privately.

For me, though, time was running out.

I'd failed to meet the criteria in Sheffield, so I doubted I would fare better in London. The process of being accepted for treatment there could take many more months.

This was precious time in which a fresh relapse might leave my brain so damaged that it might never recover.

The clinic in Mexico

After speaking to other patients who had undergone HSCT, I applied to Clinica Ruiz in Puebla, Mexico - a private haematology clinic with more than two years of experience of treating international MS patients with stem cell transplants.

That meant raising some £60,000 ($84,000) in total to pay for flights, accommodation, nursing care and the treatment itself.

It was still significantly cheaper than having the treatment privately in the UK.

I was well aware of how lucky I am to have family, friends and colleagues who rallied round to help me to raise the money.

Suddenly, in December 2016, Clinica Ruiz got in touch to offer me an earlier date for treatment.

I could start on 1 January 2017.

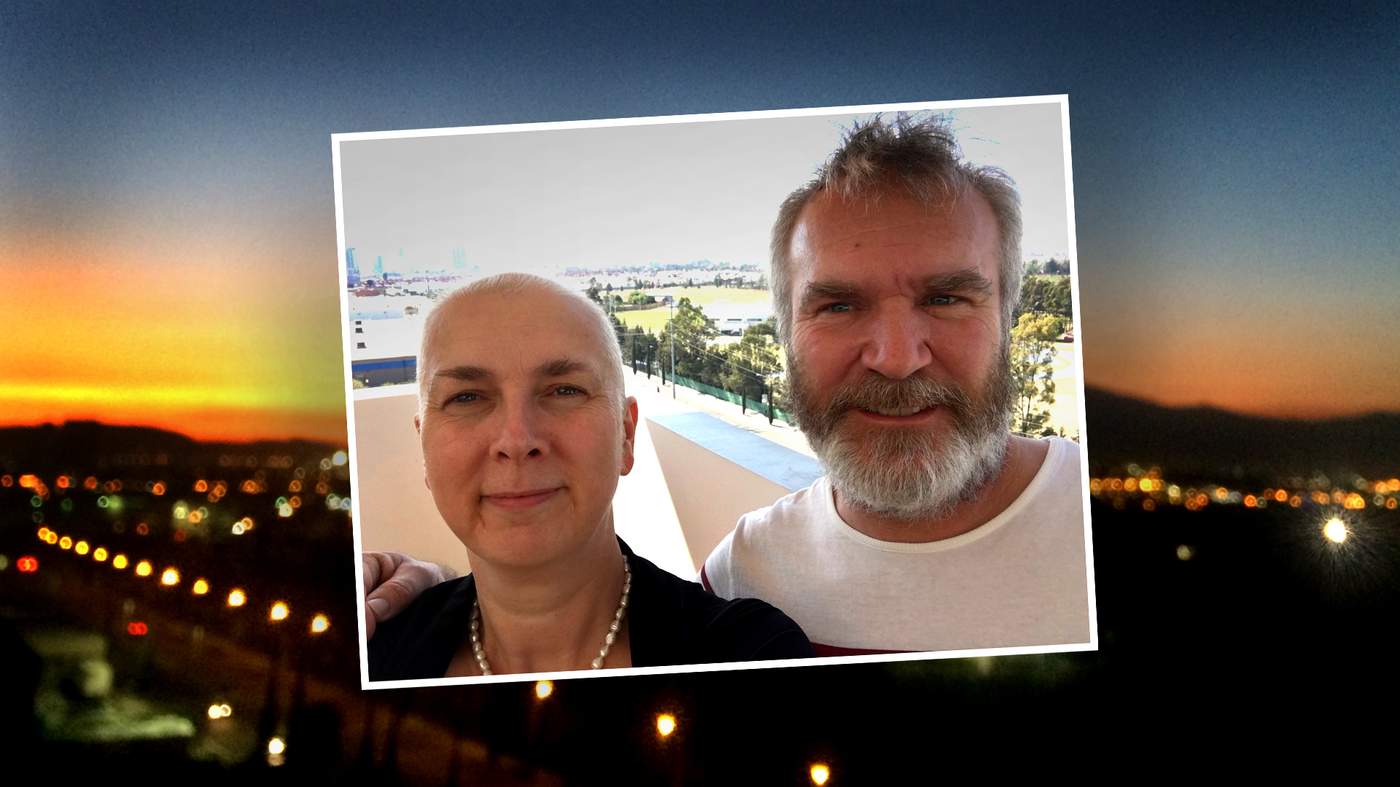

That month was a blur of mixed emotions. My oldest brother Simon offered to take me to Puebla, while my middle brother Antony would collect me at the end of treatment.

Not surprisingly, my family had serious reservations about me flying into the unknown for a treatment that carried some risk.

They were reassured by the fact that Dr Guillermo Ruiz-Arguilles, the chief haematologist at the family-run clinic, had been carrying out stem cell transplants for cancer patients for many years.

He had also treated hundreds of MS patients, with good results.

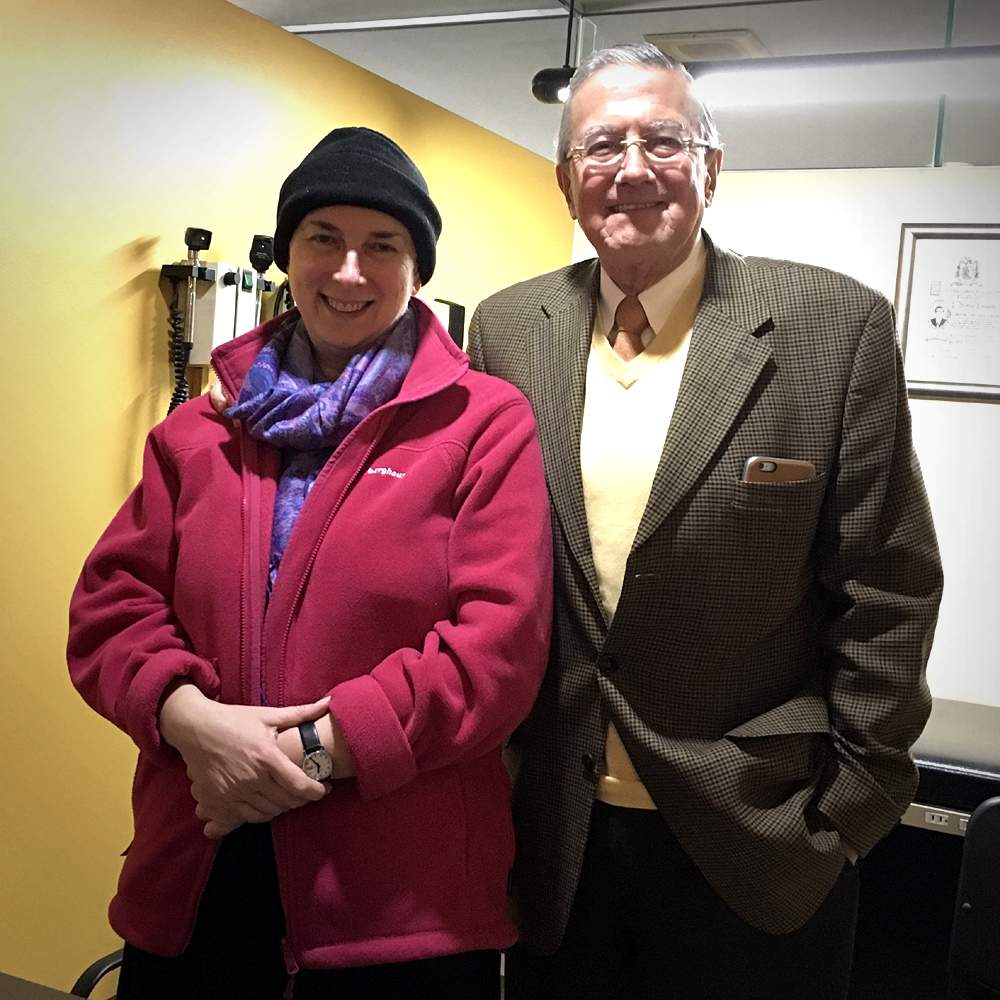

Caroline Wyatt with Dr Guillermo Ruiz-Arguilles

What also mattered to me was that Clinica Ruiz offered outpatient treatment, with an apartment for each patient to live in with a carer.

That meant that during the neutropenic phase, when the immune system is severely compromised, I could control my own environment more effectively, and ensure it remained as free of germs as possible.

I decided to pay to have a fully qualified nurse from the clinic live with me for the duration of the 28 days of treatment, for added reassurance and to avoid my brother's cooking.

The first day after moving into the apartment in Puebla was taken up by medical tests to ensure that everyone in our group of 20 international patients was fit for transplant.

On my second day in Puebla, it was time for the first chemo session.

Our sub-group of five patients plus five carers was driven to the clinic from our apartments.

I watched as the modern quarter of the city with its shiny new skyscrapers gave way to the smaller, more colourful streets of the old quarter, and wondered what on earth I was doing here.

Once at the small, unassuming clinic building, we sat back in comfy leather armchairs as the cyclophosphamide chemotherapy agent dripped slowly into our veins through a needle inserted into the back of our hands.

My nurse Yoselim (known as Joy) explained each step and brought water and sick-bags.

I was thoroughly ill during each of the four days of chemotherapy, despite anti-nausea drugs.

Early each morning, a doctor or nurse would come to the apartment to administer an injection of a mobilising agent that would encourage the stem cells from our bone marrow ahead of the stem cell harvest.

Remarkably, despite the nausea during and after those first chemotherapy sessions, I began to feel my “brain fog” lifting. I could read and remember words normally again.

No longer did I awake to crippling migraines or headaches in the morning, while the nerve pain in my fingers and toes gradually eased.

Best of all, the weight of the concrete bollards that I felt were attached to my legs and arms diminished, although the tinnitus that rang in my ears night and day did not go away.

As the days in Mexico wore on, my energy levels rose.

Though that may well have been thanks to the steroids that I was taking, and the time available to simply sleep when I needed to, rather than dragging my increasingly disabled body and brain to work.

I woke up in the morning feeling well-rested for the first time in years, without the sense of heaviness and confusion in my brain that had become worse with every passing year.

The doubts and fears that I had harboured for so many months before the treatment began to disappear.

Even the part I had been dreading most was not as bad as anticipated.

I was heavily sedated during the insertion of a central venous catheter, also known as a central venous line, into my chest.

It would help ease the passage of blood from my veins on stem cell harvest day, and during the stem cells' return a few days later.

On stem cell harvest day, I awoke feeling extremely nervous.

We were told that we would not be able to go to the loo during apheresis - the stem cell harvest - for the four hours or so that it would last.

The clinic recommended nappies, as continence is a problem for many patients with MS.

On the same day after the harvest came our penultimate chemotherapy session, with patients hooked up once again - this time to the chemo drip - for a few hours.

Our group sat chatting, reading or watching films, with some patients even Skyping friends and family back at home.

I'd brought two books with me that day, Atul Gawande's Being Mortal and AA Gill's Pour Me.

Somehow, reading about death while hoping for a fresh lease of life with a new immune system felt strangely cheering.

My stem cell ‘birthday’

In Puebla, the morning of Saturday 14 January 2017 dawned bright and sunny.

At 11:30, for one hour, lying down in a comfortable room, I received the stem cells back that would spark the growth of my new immune system.

One that I hoped would no longer mistakenly attack the myelin sheath around my nerves, as it had done for so long.

Every second of the cells seeping into my veins felt like a rebirth, although I didn't know what the outcome would be.

What was flowing through my veins was hope, for the first time in a very long time.

Every day for the next 10 days, I was monitored for neutropenia, with blood samples taken every other morning, and an appointment with the haematologist to see how the new blood cells were faring.

The cleaner who came to the flat every day left the apartment spotlessly clean and sanitized, to avoid any infection during the period in which the immune system is dangerously low.

All food had to be well-cooked in order to avoid food poisoning, while trips out of the flat were restricted to appointments at the clinic.

My appetite was smaller than usual, but still healthy. Joy cooked porridge for breakfast and delicious chicken soups or vegetable stews for supper.

To my delight, guacamole was still allowed (avocados have a hard skin, so they don't let in bacteria), so I was able to enjoy the best freshly made guacamole I'd ever had.

The final infusion was a dose of Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets a protein called CD20 that is found on the surface of white blood cells called B-lymphocytes or B-cells.

It is aimed at depleting any remaining lymphocytes following chemotherapy.

Doctors conducting HSCT treatment for MS and other auto-immune diseases at clinics around the world often use slightly different protocols, with varying intensities and drugs.

More trials are needed to show which protocol works best. But because HSCT uses a method that is already approved for cancer, and drugs that are already licensed for stem cell transplants, there is less money available for trials of HSCT than for new MS drugs, which can prove more profitable for pharmaceutical companies.

Even those wishing to study HSCT results from trials around the world have sometimes had to fight hard for funding.

So why is it taking so long for HSCT to be accepted as a treatment for MS in the UK?

“It has been very challenging,” says Paolo Muraro, professor of neurology, neuroimmunology and immunotherapy at Imperial College London, and the lead author of the largest long-term follow-up so far of HSCT for MS.

“A mixture of financial conflict of interests, scepticism, conservative views of MS being a ‘non-malignant’ disease and consequent reluctance and slowness in adopting new therapies involving any risks has slowed down progress.”

The journey home

By the time I left Mexico on 28 January with my brother Antony helping me into a wheelchair to navigate the airport's long corridors, I felt very different to the patient who had arrived with such trepidation just 28 days earlier.

By now I had almost no hair as the chemotherapy had caused it to drop out, but that was a small price to pay if it meant I now had the chance to grow a new, functioning immune system.

After a brief stop at duty free, I also had a rather wonderful sombrero to hide beneath.

Once back in the UK, I was in quarantine at home for several months while my new immune system rebooted. But for me, and for some others, the recovery period has proved far harder than the transplant itself.

Chemotherapy is an aggressive treatment, with many after-effects. It's not surprising that the NHS discourages patients from seeking such serious medical treatment abroad - not least because it has a duty of care to pick up the pieces if anything goes wrong.

For the first weeks back at home, I slept a lot as I came down from my steroid high, and my energy levels crashed. The second week brought some improvements to my balance, while the third week saw me able to walk further than before, albeit still with support from my trusty walking stick.

I continued to avoid people, colds and flu.

After the first months, I was able to start stretching exercises at home, and I noticed that the blurriness in my left eye was receding, although my brain and limbs still felt fragile and unreliable.

But the following months proved far more challenging.

Chemotherapy has a major impact on hormones, especially on top of the menopause.

For several months, sleep proved elusive, as I lay either shivering in a cold sweat or wide awake with hot flushes.

Most HSCT patients over the age of 32 will be left infertile by the chemotherapy, according to the researchers in Chicago. This is a major consideration for any younger patient. MS had left me unable to have children, so that wasn't a worry for me.

Then the migraines began to return, along with the painful stiffness, spasms and numbness in my limbs.

It is often said that the recovery from a stem cell transplant for MS is a rollercoaster ride.

A little over one year on, that remains true for me and for many others.

Twelve months on

Today, I quite often feel worse than I did before HSCT.

I still need to rest frequently during the day, and when I use my energy for work, I have none left for anything else at all.

But there are sunnier days when I feel a little better than I did immediately before the treatment, and then my hopes soar.

Of the other HSCT patients with whom I keep in touch via several vital support groups on Facebook, some have seen improvements and are overjoyed.

Once again, they can play a full part in family life, and work without exhaustion. Many train hard at the gym or at home, doing their best to regain limb function and balance that was lost over many years.

Others report little change.

And a few have said that they now feel worse than they ever did before HSCT, and wish they had never had the treatment.

Some have had fresh relapses since their transplant, and wonder whether to have HSCT again, or re-start MS drugs. It isn't yet clear why there is such a wide variation in response.

Much about the long-term impact of HSCT on auto-immune diseases, from MS to systemic sclerosis or Crohn's disease, is still unknown, and may remain unclear until the causes of these diseases are better understood.

Soberingly, over the past year, some patients at international centres have died while having HSCT, making clear that it is not a treatment to be entered into lightly, however effective it can be in halting progression for some.

Many patients have struggled after transplant with everything from migraines, headaches, swollen feet or agonising neuropathic pain in the hands and feet, to viruses or bacterial infections that affect the bladder.

They can also develop other common infections that resurface in the body when the immune system is fragile, such as the Epstein-Barr virus, herpes or shingles.

However, my latest MRI brain scan shows that so far, I have no new lesions on the brain.

It's a sign, I hope, that I shall be among the lucky ones for whom the treatment does halt further MS progression for several years.

I asked Professor Muraro of Imperial College London how long that benefit might last for those who respond to HSCT.

“In the very long term we do not know,” he says. “We know the durability of effects is still good at five years, but the longer term is a question that could be addressed.”

After his last study, he concluded that “with this procedure, we've shown we can ‘freeze’ a patient's disease – and stop it from becoming worse, for up to five years. However, we must take into account that the treatment carries a small risk of death, and this is a disease that is not immediately life-threatening.”

So how close are researchers to finding the causes of MS?

“I don't think anyone knows how close we are. It is clear we are making stepwise progress. The critical - small or giant - leap may happen at any time,” says Professor Muraro.

“Studying HSCT by comparing the immune system before and after treatment provides a great opportunity to find out what may have gone wrong that is corrected by HSCT in the patient where clinical MS is shut down.”

I know that I can't, as yet, repair all the damage done to my brain and central nervous system by decades of MS.

But I am an optimist, and shall remain so while my immune system finishes reconstituting itself fully by the end of this year, some two years after I started treatment.

My goal is to stay healthy enough in the coming years to be there for my wonderful parents as they age, and for my brothers, sister, nieces, nephews, great-nieces and friends.

I'd love to be able to continue both to work and enjoy life, rather than sleep-walking through the rest of it in a haze of crushing fatigue.

Whatever happens in the future, I am grateful to have had these two years of hope.