The darkened entrance to 7 James Street was about to give up a gruesome secret.

The police sergeant picked his way up the narrow, carpeted stairs to the first floor landing, outside the front door of flat one.

The door was locked. He shook the handle and it rattled where the lock had worked loose. Standing back he aimed a forceful kick.

The lights inside were not working; the pre-payment meter card had run out ages ago. The pitch-black hallway was strewn with litter. All three doors leading off it were shut.

Opening one, the officer walked into the kitchen and through to the bathroom; the light of his torch traced a number of spent matches and cigarette butts, stood up on their ends, strangely arranged in a line around the rim of the bath.

Another door led to a room empty save for two mattresses propped against the wall. He flicked his torch towards the third door. There was blood on it.

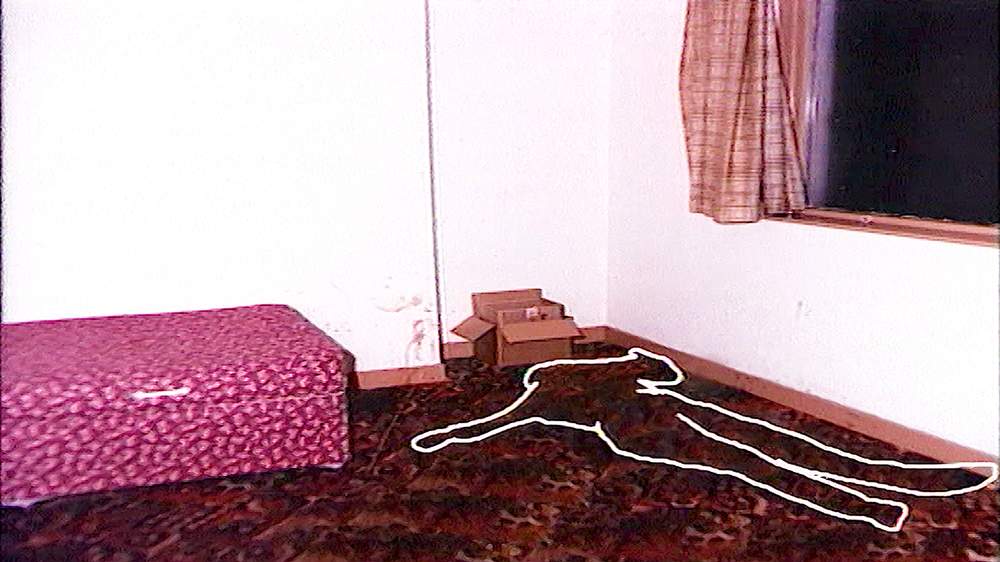

Inside, a bare divan was illuminated by the orange glow of a street light. On top of it an opened but unused condom. At the bottom of it, the body of a woman.

Lying on her back, she was fully clothed, her t-shirt and stone-washed jeans partially covered by a black leather coat. Even in murky light it was clear; she was dead.

As the officer radioed for back-up, a woman waiting on the landing outside the entrance to the flat started to cry.

Minutes before she had gone to the police station; she had lent the flat keys to a friend, she explained, but the friend had not been seen for days; she was worried.

Her friend, the young woman found dead above a betting shop in Flat one, 7 James Street, Cardiff, had been murdered.

Her throat slit so deeply, she was virtually decapitated. Her hands, a last frantic defence, slashed; her chest mutilated, her wrists cut. Many of the 50-plus stab and slash wounds were inflicted after she had died.

Her name was Lynette White, a 5ft 4ins tall 20-year-old with blonde hair and bright blue eyes.

Those who knew her said she was popular, quiet, kind, friendly and unfailingly polite.

To those who loved her, she was much, much more than that.

"I remember we used to fight over who would do her ringlets," recalls her Auntie Lyn, after whom Lynette was named.

"Lynette had fantastic skin and a fantastic personality. I used to call her my protégée. We used to say she could be a model and look after me in my old age."

In the cold, dank flat was the body of a woman whose childhood visit to Father Christmas had been lovingly cherished in a photo frame; a girl who spent time out of school looking after horses at the city farm; a daughter, grandchild, niece, sister, girlfriend.

She liked music, Whitney Houston's I Wanna Dance With Somebody and Freddie McGregor's Just Don't Want To Be Lonely and loved romantic films. Her dream was to fall in love and have a home filled with children.

It was the idealised kind of family life she had never known. Her parents had split up when she was 18 months old. Her father insisted Lynette stay with him in Cardiff, while her mother moved back to Essex with Lynette's half-sister.

But what she lacked in a mother, her paternal grandmother, her Nanna, with whom she lived in her early years along with her aunties, strove to make up for, lavishing their "little gem" with love. Lynette grew particularly close to her Auntie Lyn who she called her "little mum".

Lynette moved a few miles away from them when her father Terry re-married. Her step-mother Carol had two other children, a girl and a boy.

Then aged 12 her fragile emotional world imploded. Her beloved Nanna, her touchstone, the matriarch who had been the constant in her life from a baby, died tragically. She was only 56.

The emotional agony may have rendered Lynette especially vulnerable to the heady onslaught of adolescence.

She was to pay a savage price for that vulnerability all too soon.

Not long before she was murdered, she spoke to a BBC reporter investigating child prostitution in the Welsh capital.

She told him that aged 14 she was abducted by a gang and taken to Bristol where she was drugged and forced into sex work. She escaped and returned home but a few years later began "working the beat" in Cardiff's docklands.

Her Auntie Lyn was horrified when she eventually found out.

"I've no idea at what point she went down that path," she says. "I lie awake at night thinking 'could I have stopped her? If I'd known could I have done something?'

"But I really don't think I could have done anything to help. She was so in love with that guy. She just wanted to be loved."

Lyn had cooked Lynette Sunday roasts and helped arrange surprise birthday parties, hoping desperately to boost her ailing self-worth and keep her life on track.

"We were having a laugh in my kitchen, it was around New Year," her auntie says.

"I was doing her hair and we were talking about a boyfriend she'd fallen out with. I told her that one day you will see the right man, you will look in his eyes and you will know that he really loves you'.

"And she turned around and looked at me and said 'oh no, no, Auntie Lyn. No-one, no man will ever love me'."

Slowly, Lynette drifted out of reach of her Auntie Lyn.

The torturous thought of her alone that night with just a candle for light, has cost her too many sleepless nights. But out of respect for the privacy of the very few remaining members of Lynette's immediate family she will not say any more.

The Whites were virtually destroyed not only by what happened at 7 James Street but by what followed.

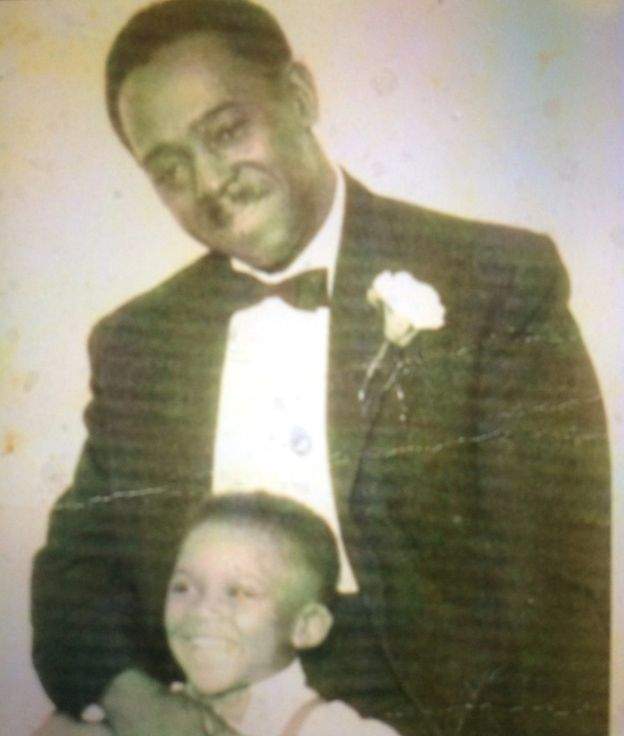

Lynette's father Terry and family at her funeral

They were not alone.

The unrelenting aftershocks of Lynette's death were widely felt and unnecessarily ruined the lives of many others.

This was only the start.

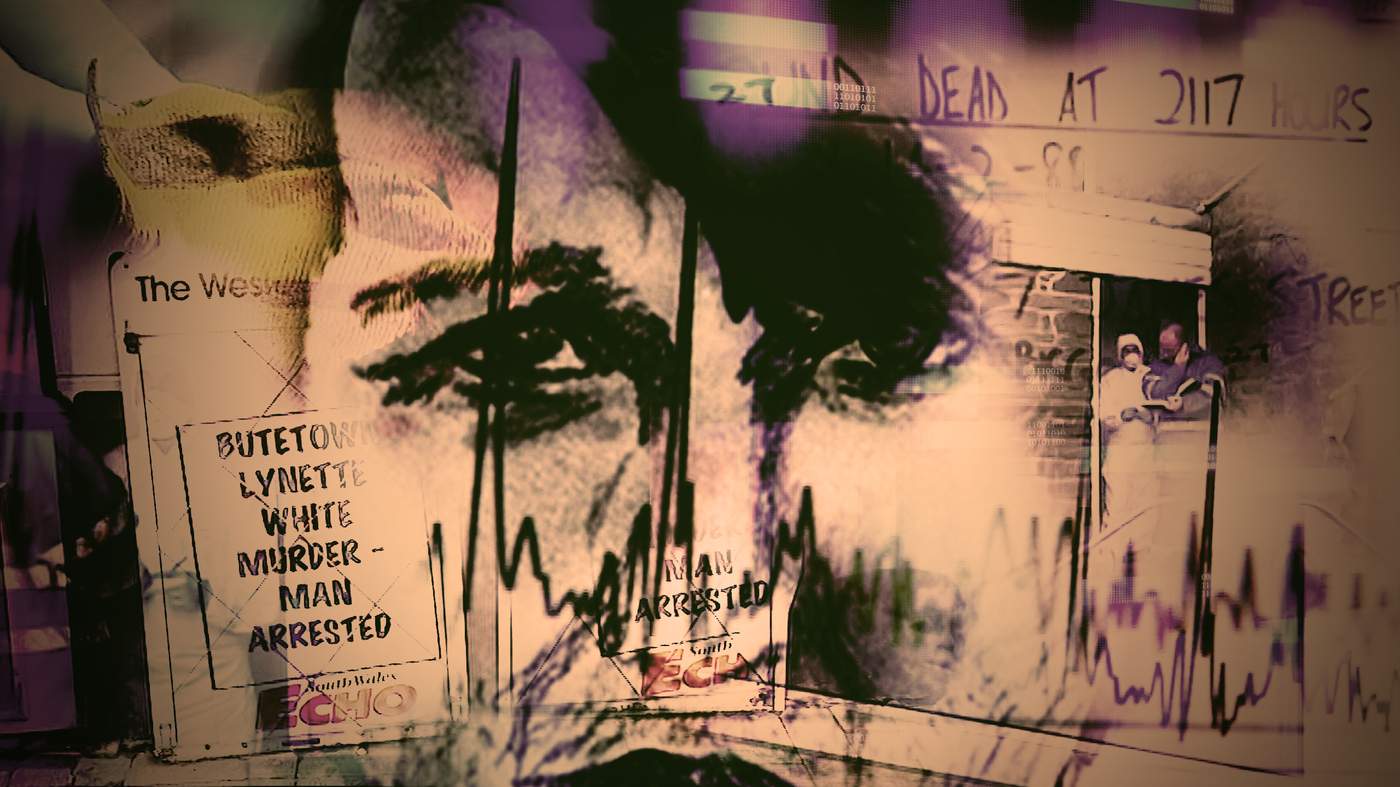

The subsequent scandal surrounding the police investigation led to stigmatising innocent men in one of the most notorious travesties in British legal history and its largest police corruption trial, the final chapter of which has only just closed 30 years later.

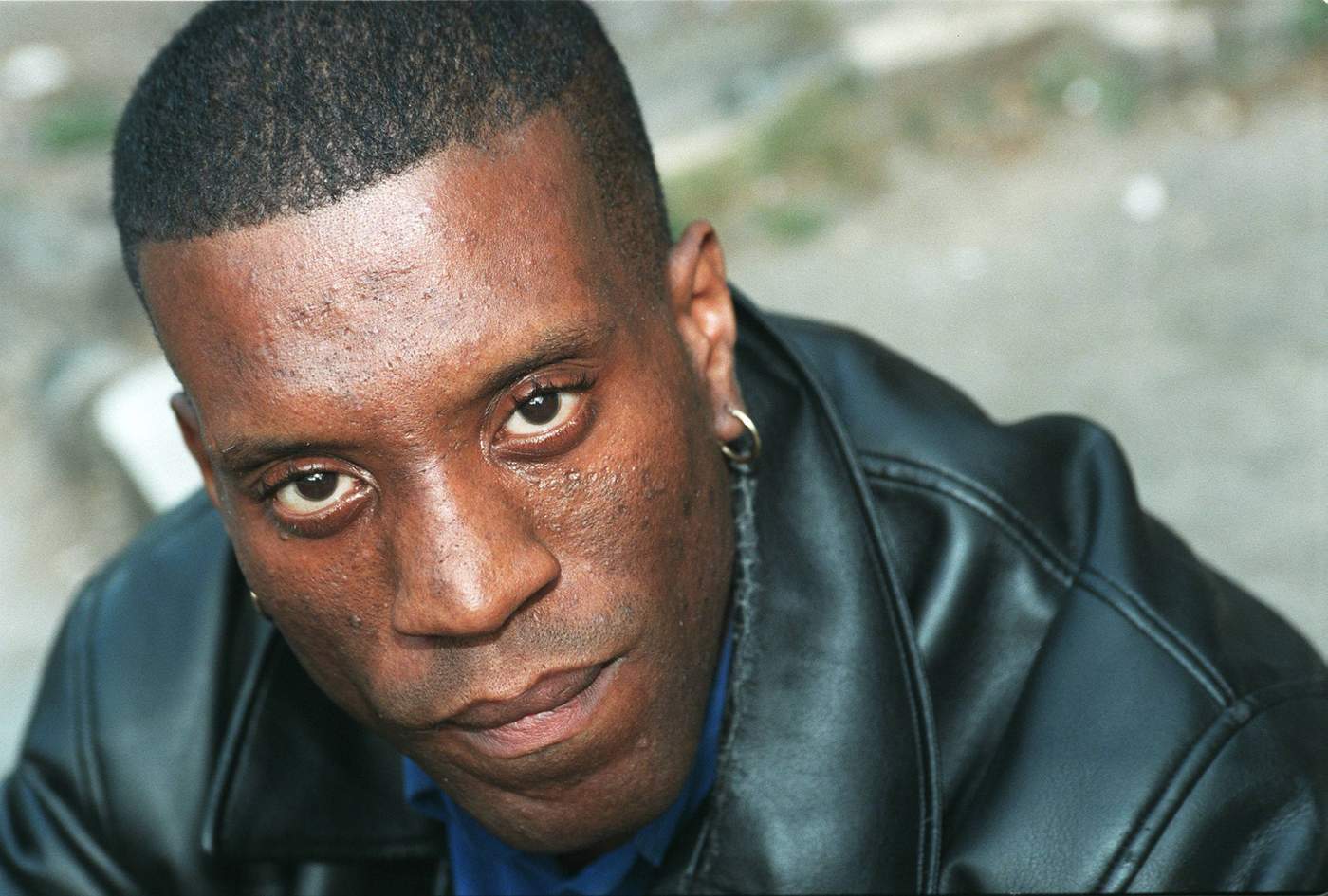

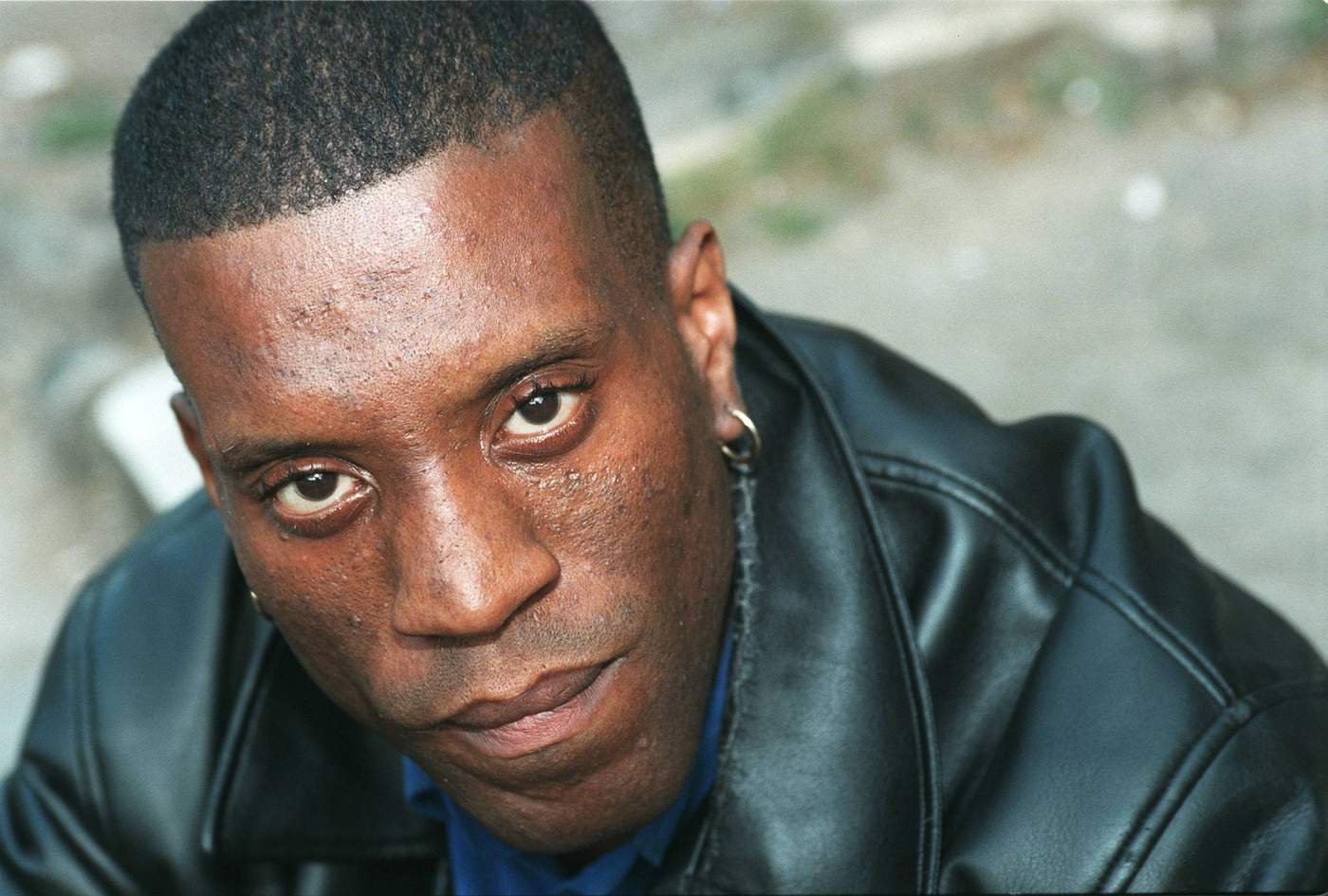

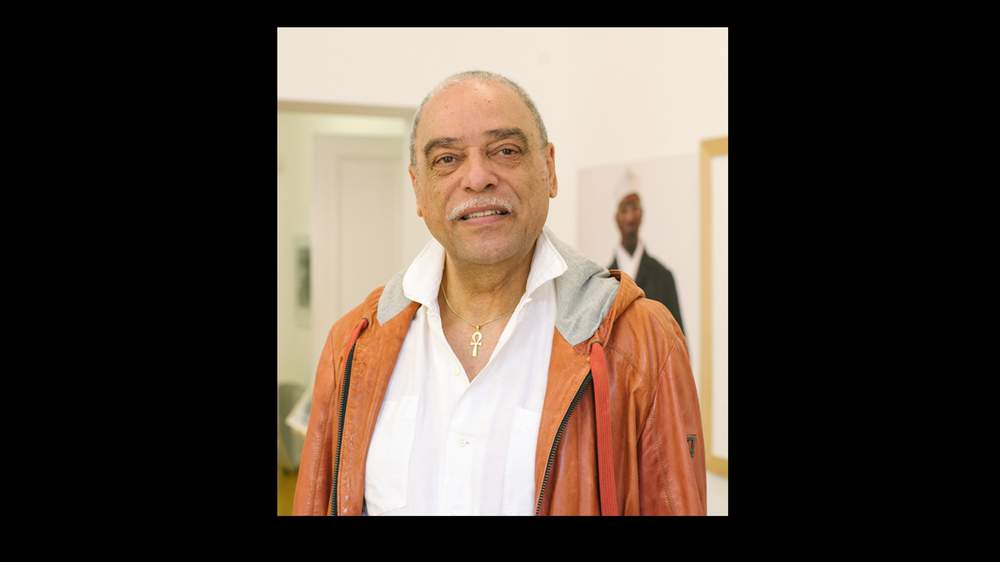

"Stephen King couldn't write a better horror story than this," says 60-year-old Tony Paris whose life changed irrevocably the moment he was cast as one of its leading characters.

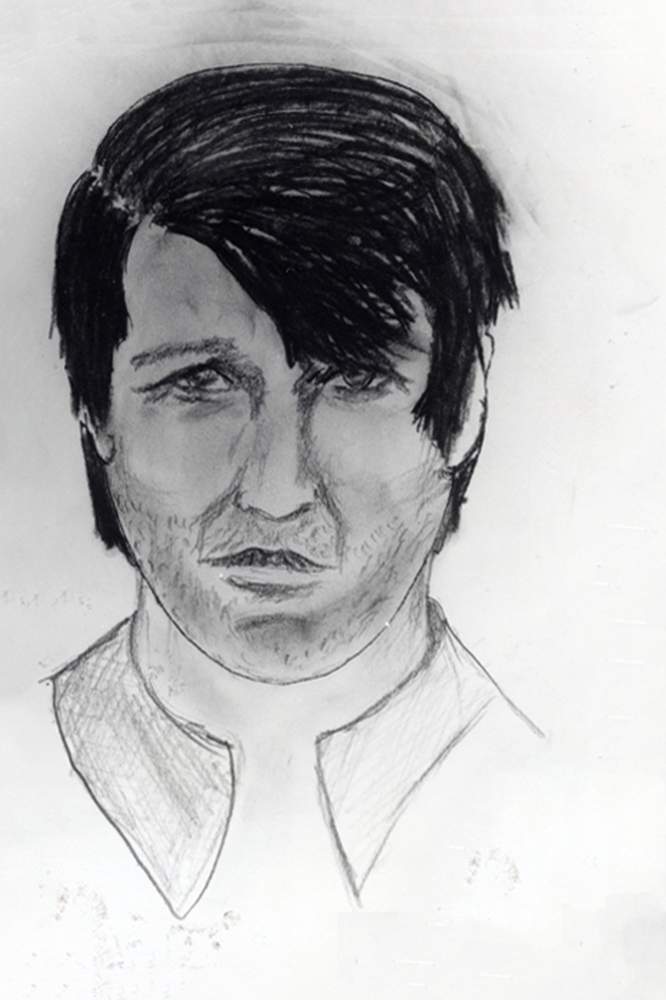

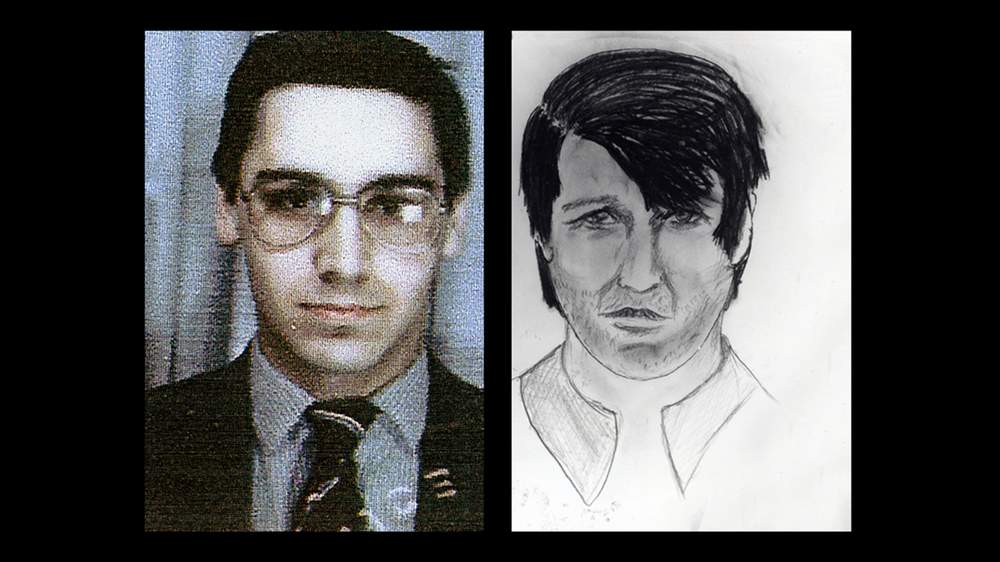

Within weeks of the murder the BBC's newly-launched Crimewatch programme revealed a compelling early lead in the murder hunt.

A photo-fit was shown of a man who had been seen by a member of the public crouched in the doorway of 7 James Street. His hand was bleeding heavily; he was crying and mumbling incoherently.

"He is very distinctive," said the then head of South Wales Police CID, Detective Chief Superintendent John Williams, who described the murder as "a vicious, frenzied, sadistic attack".

"He has got dark brown, greasy hair with lightening towards the front of it. He's about 35 to 40 years of age and between 5ft 8 and 6ft tall."

So the man police were hunting was distinctive. He was also white.

Breaking news 10 months later; five men had been charged with the murder of Lynette White.

They were all black.

The first John Actie knew of the murder was the Monday morning of 15 February 1988.

“I was coming out of the house and a guy I knew was walking up the road,” he told BBC Wales Investigates. “He said to me ‘did you hear about the murder?’ I told him no, what murder? He said it was Lynette White and I said ‘who’s Lynette White?’.

“It was in the (South Wales) Echo and there was a picture of her and that’s when I realised it was Miller’s girlfriend.”

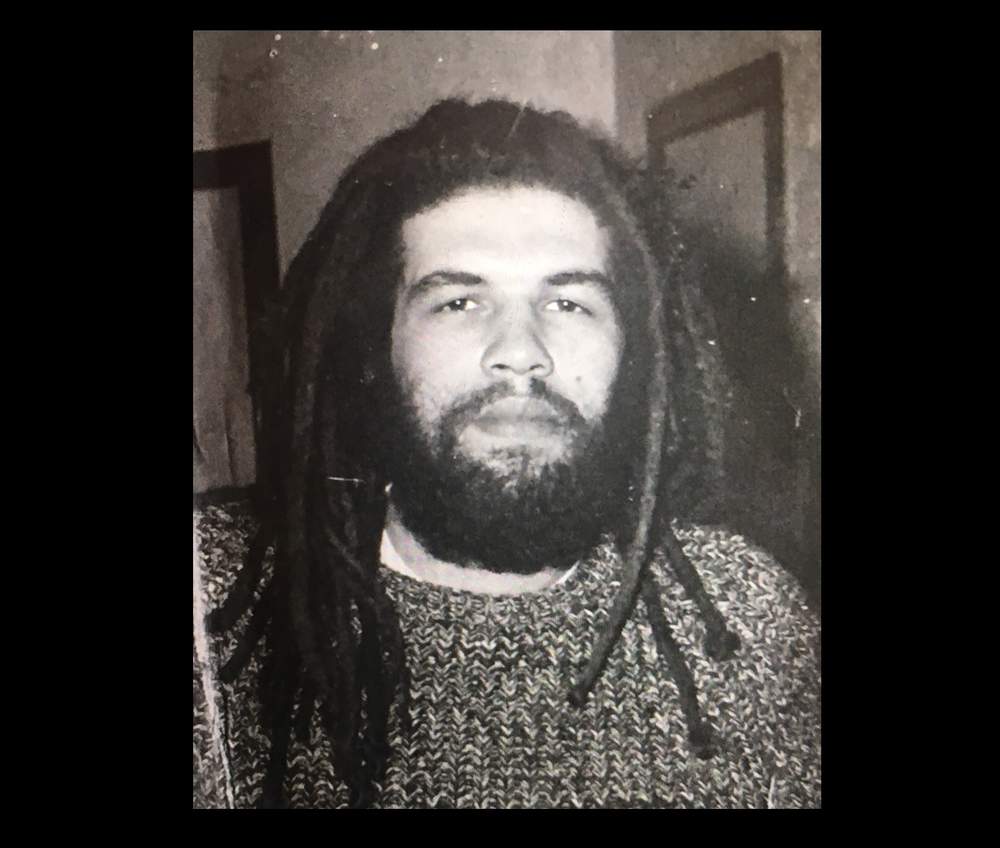

Stephen Miller – known locally as Pineapple on account of his dreadlocks tied up on top of his head and a penchant for pineapple juice - had been going out with Lynette for a couple of years. He had moved down from Brixton after they met through his brother who was living in Cardiff.

He had broken down at the “hammer blow” news of her death and was willing to do anything to help.

Naturally he was a possible suspect but nothing suggested to police he was the killer.

The 22-year-old told how he had been frantically looking for Lynette. He was worried about her but it is likely he also wanted her earnings to pay for his cocaine habit.

They had argued five days before, he explained, and she had not come home to the flat they shared in the nearby Grangetown area of the city.

Stephen Miller, Lynette White's boyfriend of two years

He had no knowledge of the flat at 7 James Street, rented for business by Lynette’s friend and fellow sex worker Leanne Vilday.

It is still not clear where Lynette was in her final days. The police had also been looking for her.

She was due to be a witness at an attempted murder trial and an arrest warrant had been issued for her.

That trial was halted and following forensic tests any suspicion that she had been silenced by anyone involved was discounted.

There was no link between that case and Lynette White’s murder. Police investigating were unsurprisingly working on the theory that she had been murdered by a client.

The inquiry had a prime suspect, a man known to the police, dubbed Mr X. But that investigation ended abruptly in September when blood tests ruled him out too.

The detectives were back to square one.

By then two of the force’s officers with reputations for getting results - Detective Inspector Graham Mouncher, who took over as lead officer, and Inspector Tommy Page – had been pulled in to rescue the floundering investigation.

Meanwhile, uniformed officers had conducted 6,000 house-to-house inquiries asking everyone in the area, including John Actie, to fill in a questionnaire.

There was no love lost between him and the police.

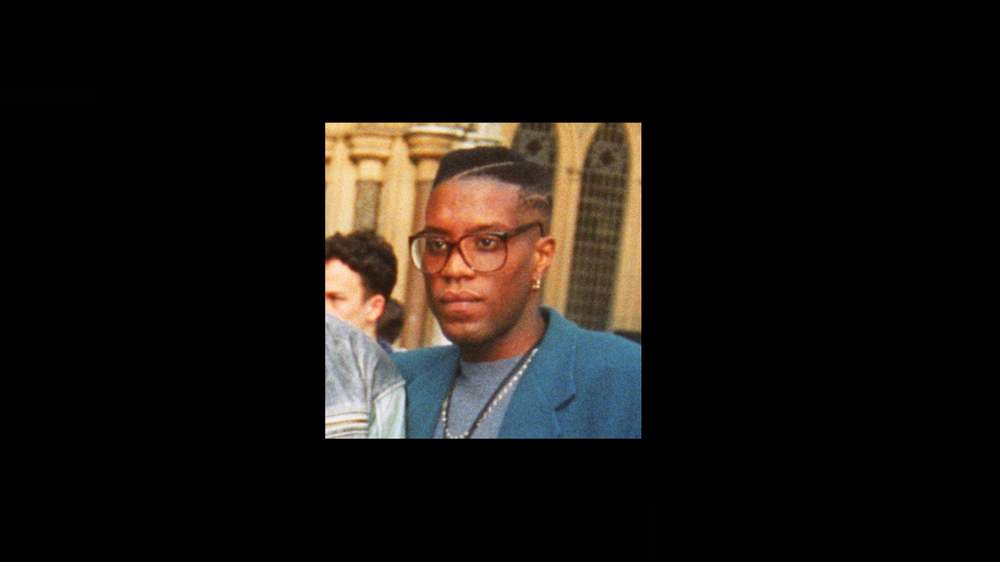

An incident when he was 19 remains vivid in his mind.

Arrested for criminal damage at a nightclub he says he had never been to, he recalls being taken to Cardiff's central police station and "badly beaten" by a group of 11 police officers.

He was subsequently charged with assaulting them. After giving his side of the story, all charges against him were dismissed by a magistrate.

But time would prove it to be a Pyrrhic victory.

John Actie was a name widely known in Cardiff. He had a reputation as a "hard man", someone you did not want to cross.

Once a promising rugby player, he had played well above his age group as a flanker or Number 8 for Cardiff Youth.

His dad, Charlie Actie, a seaman and steel erector, part of a big, long-established docks family, was always there to urge him on.

Schoolboys Cup victory at Cardiff Arms Park: Winning try scorer John Actie holds the captain aloft, with David Bishop crouching down (bottom left)

His son easily matched the skill of his team-mates, David Bishop and Mark Ring, both of whom went onto play for Wales. But John Actie was not destined to wear the "red jersey".

"John was a brilliant player," says David Bishop, who describes him as his "best friend, like family".

"Let me tell you, he was certainly capable of playing rugby at the top level."

Aged 12 John was round at David's house when there was a phone call to say he had to come home right away.

“My dad had died," says John, 56. "He was just 42 and had lung cancer. I was devastated. We were very close and he’d always been there to keep me in line. I went completely off the rails.

“I started drifting in and out of borstal, approved schools, running away, mixing with different people, doing stupid things. Then I got sent to a detention centre… you just progress.

"My mum was always there for me but she couldn’t control me like my father. She had seven kids and worked hard to provide for us.”

By the age of 22 John had served a three-year term for robbery and a 12-month jail sentence for possession of cannabis.

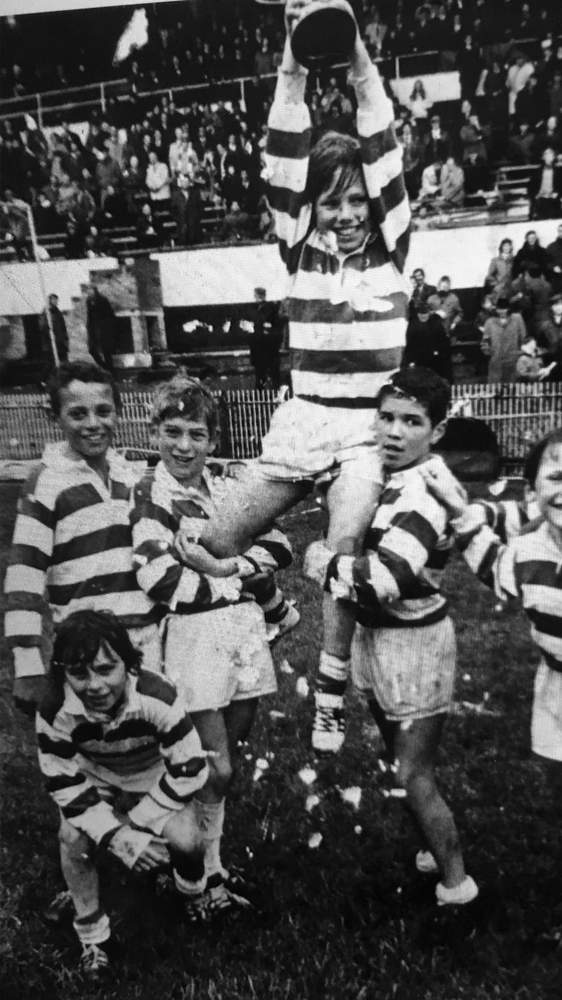

Doing security work, debt collecting and working on the door at nightclubs like the Casablanca, a well-known music venue in the docks, he aggravated the police by "refusing to bow down to them" and by organising illegal all-night Blues house parties held at various locations selling drink and playing reggae and soul music.

John was working the door at the Casablanca nightclub on the night in question. The club was razed in the 1980s to make way for a car park

In his book entitled Bloody Valentine published in the early 1990s, Cardiff-born author John Williams described John as a “bullet-headed 6ft-something guy built like the proverbial brick shit house”.

“Around 1988 the Docks police figures John Actie for Butetown’s heaviest cocaine dealer, a Yardie-connected drug baron,” Williams wrote.

“Talking to people more or less in the know, John Actie was not the Mr Big that the police made him out to be. Yes, he was [at one time] a drug dealer but not on a grand scale. But he did have a reputation, an image… Basically John Actie was the baddest m-f in the neighbourhood.”

Violence, or the threat of it, may well at one time have been John’s stock in trade. But Lynette White? The murder horrified him.

A woman stabbed over 50 times was, he says, the work of a “lunatic” and his priority was the welfare of his wife, and two daughters, a four-year-old and a new-born.

“If I’d known anything, I’d have reported it the next day,” he adds.

Meanwhile detectives were getting nowhere fast and the pressure on them intensified.

“It was all to do with the new barrage, the regeneration,” John says. “They wanted to clean this area up and make it good for the yuppies. No one wants to live here when there’s skulduggery like that in the area.”

Ten months earlier the multi-million pound Cardiff Bay Development Corporation had got under way. Its quest was to transform the city’s one time world-famous but now desolate docklands, and boost Cardiff’s economy as a world-class maritime city.

Something like £2 billion was being sought from investors and Lynette White’s unsolved murder was hardly seductive.

Cardiff then was virtually unrecognisable from the city it is today – one of the fastest growing in Europe. 1980s Cardiff had a smaller feeling to it.

For decades it had an uneasy relationship with its dockland and its residential area known as Butetown, named after the 2nd Marquis of Bute whose family established a dock when Cardiff was an insignificant village.

The industrial revolution and coal from the south Wales valleys had seen Cardiff morph into one of the busiest docklands in the world exporting 12.6 million tonnes a year at its zenith.

Its Coal Exchange witnessed the signing of the first million pound cheque in 1904.

“James Street, the one-time hub of dock life, pulsed with vitality,” wrote Tiger Bay poet Harry ‘Shipmate’ Cooke. “Tall buildings full of clacking typewriters, clerks, ship brokers, agents and things maritime. At street level, shops of every degree, elbowing each other for attention.”

James Street, the beating heart of Cardiff docks, in the early 1900s

Back then Butetown was known the world over as the legendary Tiger Bay.

It had a reputation as a hotbed of raucousness, brawling sailors, prostitution and illegal gambling – it was a port after all – but there was something more distinctive about Tiger Bay.

Over the years many visiting seamen settled there forging a community unparalleled in diversity and tolerance. It is said that at one time 57 different nationalities lived there.

Welsh girls commonly demonised by society and ostracised by their families for falling in love with men of colour joined the coalescence. It was them against the world.

Arthur Actie, John’s grandfather, a seaman from St Lucia, docked in Cardiff around the time of Britain’s first race riots in 1919.

Demobbed servicemen vented their anger over unemployment at the men of Tiger Bay, many of whom had tried to join up but were rejected and as a result had jobs.

John's parents Charlie and Maria Actie

John’s grandmother was half-Welsh, half-Barbadian, his late mother, Maria, from Cardiff, descended from the influx of Irish workers into the city.

John’s family embodied the history of the city. And in 1988, he, the latest generation, would be indelibly written into its next, more shameful chapter.

For nine months police had been looking for a single white man. Suddenly an entirely different set of suspects were taken in for questioning.

At 07:30 on 9 December four police officers were outside John’s front door.

“I said ‘what do you want?’” he recalls. “They said the superintendent wanted me brought in, something to do with the Lynette White inquiry. I said ‘are you mad? you’re having a laugh aren’t you? I’m not going anywhere, now get away from my door’.

“He said if I didn’t go he’d call back up and they didn’t want to do that with my wife and kids in the house. I told them to get back in the car and I’d get dressed.

“As soon as we started the first interview and they said I was in the James Street flat I turned to my solicitor and said ‘Stuart, they’re fitting me up’. It was terrifying.

“They were putting me with a group of other guys who I knew from the area but didn’t go around with. It didn’t make any sense. We didn’t bother with each other. One of them was my cousin, but even we weren’t close.

“What they were coming out with was so crazy, at one stage I said ‘I’ve had enough of this I’m going back to my cell’.

“They said they had statements from people who were in the flat. I’d never even heard of these people, didn’t have a clue who they were.

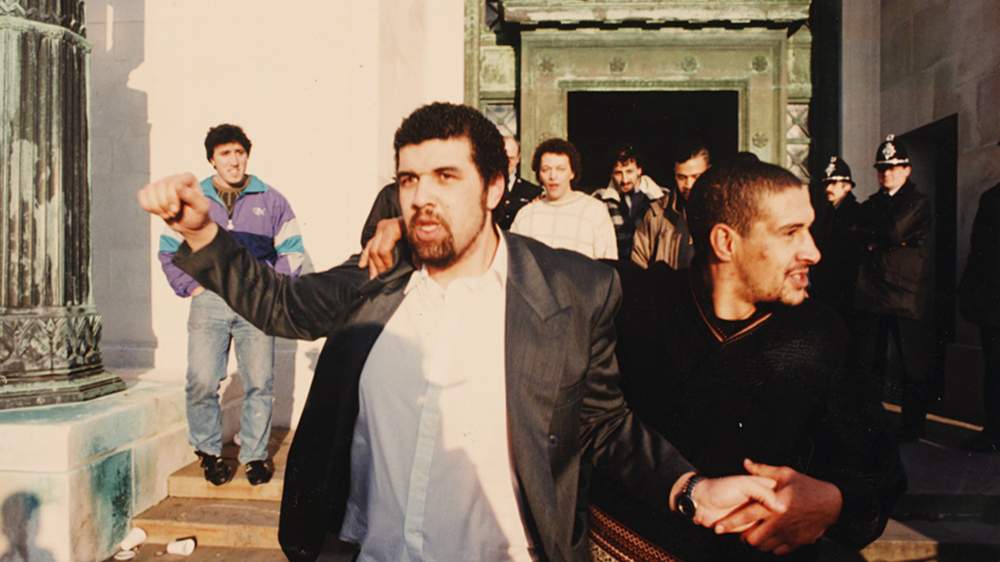

“Two days later we were led handcuffed from our cells and lined up. There must have been about 30 or 40 of them, CID, in there all smiling and laughing. ‘John Arthur Actie, you are charged that on the 14th of February….’ I had a mint in my mouth and I nearly choked on it. It felt like the end of the world.

“It was boiling hot in my cell and I remember I was pacing up and down saying ‘Me? A murderer? Me? No, no, no… I can’t believe this’.

"There were tears in my eyes. It was like my dad had died all over again. I asked if I could make a phone call and one of them said ‘in 25 years John’.”

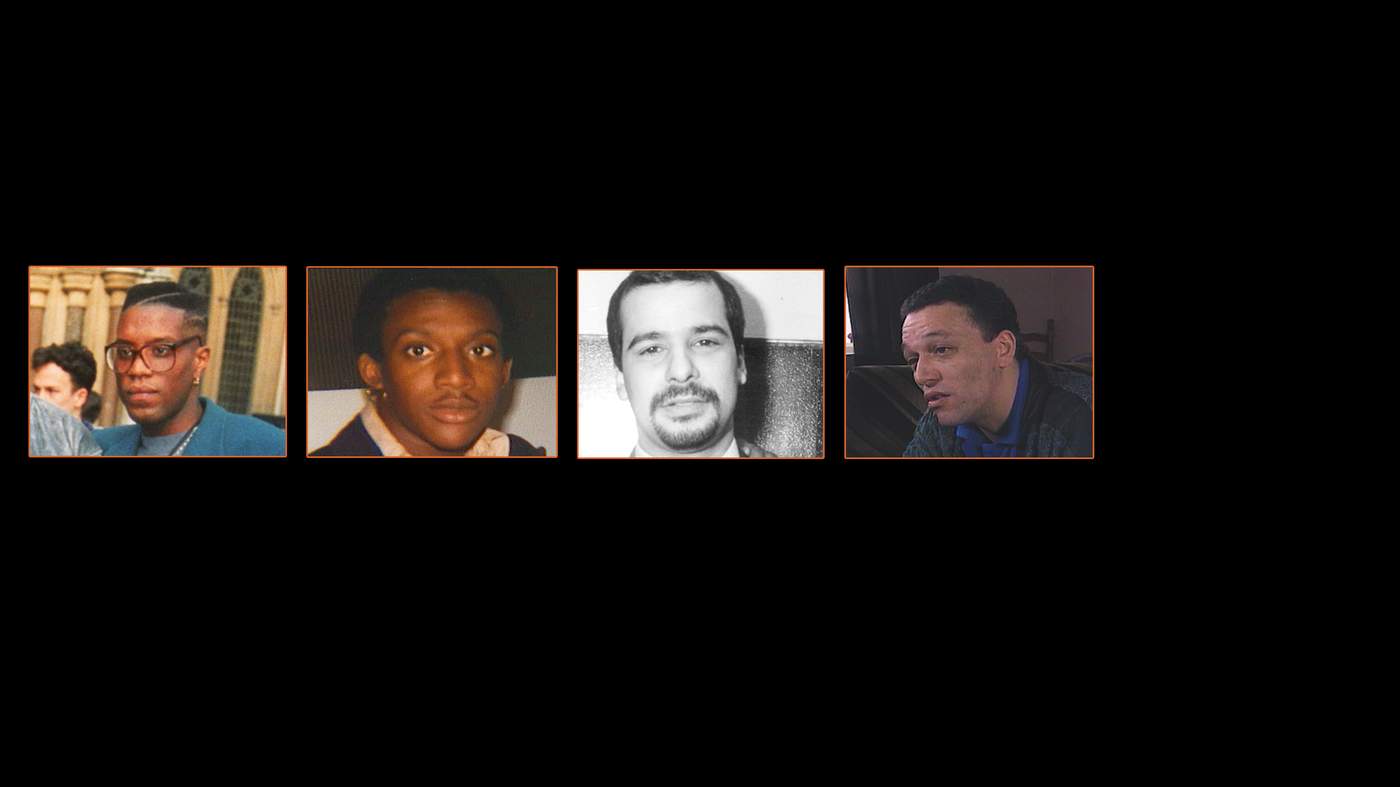

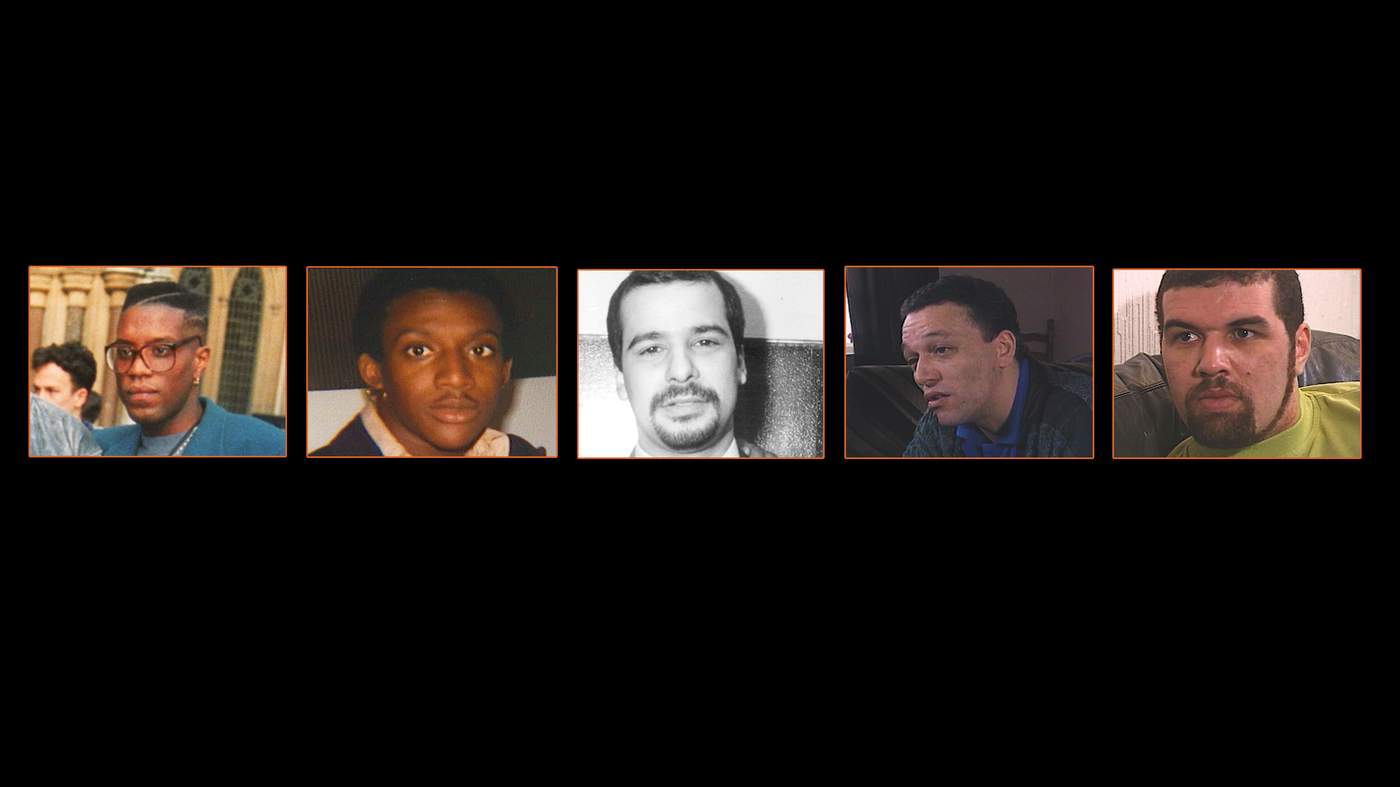

The four other men charged alongside John on 11 December 1988 were Tony Paris, 30, Stephen Miller, 22, Ronnie Actie, 30, and Yusef Abdullahi, 26, all of whom lived in Butetown.

They were later to become known as The Cardiff Five.

"I stood in the dock and the foreman was asked if they'd reached a verdict," Tony Paris recalls.

"He said 'guilty'. I was thinking 'what?'. My brother collapsed in shock, he went down, bang, it was terrible. I turned round and said to my sister 'Rosie, I haven't done anything'.

"I looked at the jury and some of them were crying. My hands were locked onto the wooden bar of the dock. When they tried to lead me away, my hands wouldn't come away, I couldn't move."

Tony Paris stood apart from his co-defendants. He had no history of violence; he had never been to prison. He had three previous convictions, two fines for shoplifting and one for driving without insurance.

In fact, he was widely known for avoiding confrontation at all costs and for fainting at the sight of his own blood.

Everyone in Butetown knew Tony Paris. He offered what could euphemistically be called a "collect and delivery service".

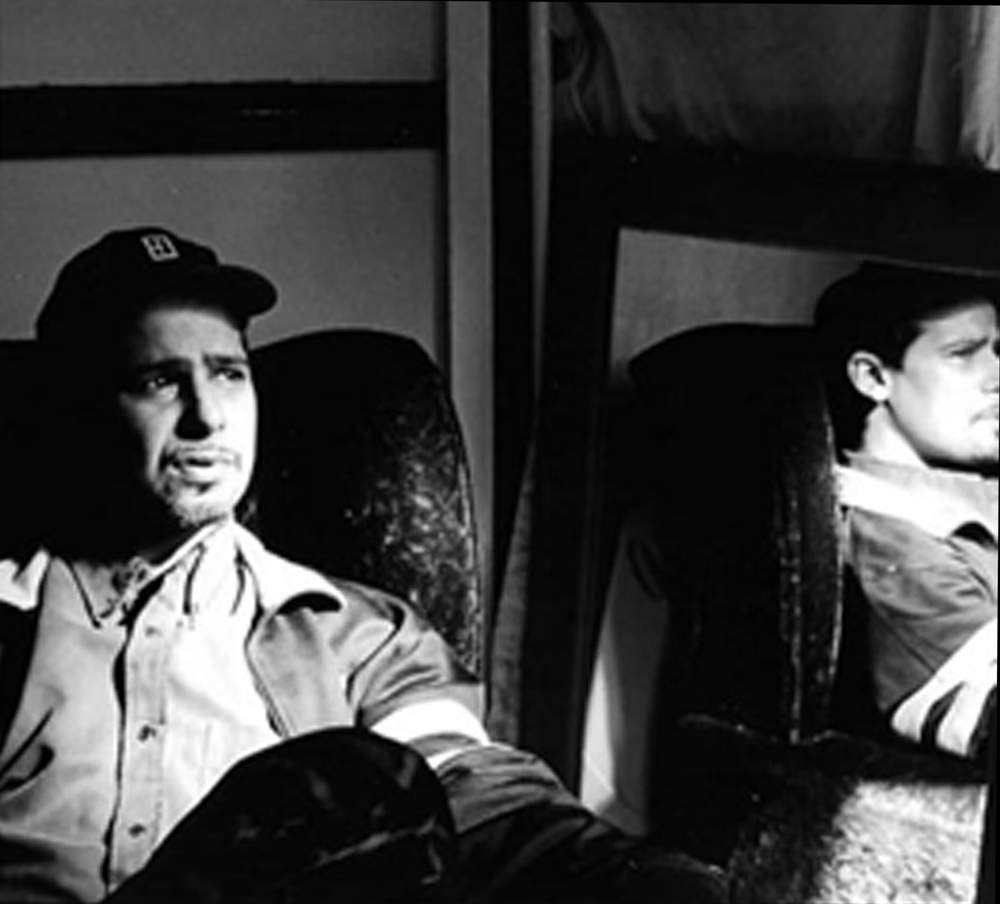

Tony Paris had been collecting glasses in the Casablanca nightclub at the time of the murder

"Shoplifting in them days was easier, less security," he says.

"Someone would say 'ah, there's this beautiful dress Tone' and I'd say 'give me the details'. 'You know my size don't you Tone?' 'of course I do, I know everyone's size'.

"They used to call me Pockets. I'm round everybody's house in the docks. I know everyone and everyone knows me. I'm trusted."

By the 1980s, Butetown, the home of Cardiff's red-light district was a virtual 6,000-strong ghetto, just south of the city centre.

Many in the rest of the city felt nervous about venturing "under the bridge", a railway bridge near Cardiff Central train station, its unofficial gateway. Butetown was quite literally the wrong side of the tracks.

Butetown just beyond Cardiff Central rail track

Loudon Square: Concrete tower blocks replaced a square of elegant houses, at one time the city's most affluent area

The name Tiger Bay had been consigned to history after a 1960s slum clearance; its historic yet dilapidated architecture replaced with a concrete council estate of maisonettes and high-rise tower blocks.

Unemployment was high especially among the young who said they were discriminated against on account of their postcode.

"It might have been different outside of the docks but growing up there I didn't see racism," Tony says, "because I was brought up in a community with blacks, whites, Indian, Chinese.

"Doesn't matter about your religion, your colour, we're docks boys, we stick together. We were different to other communities; it was 'all for one'.

Tony, a football-mad child with his Uncle Charlie. His parents had come to Cardiff from the Caribbean island of Nevis

"I'm no trouble. I don't go to jail; I'm not a jail person. When I got caught shoplifting I held my hands up. I went to court and pleaded guilty, got fined and went home. What am I going to argue with police for? It's stupid.

"I was this little 5ft 2 black guy. I used to wear two-toned suits, with a hat, Crombie and carry a cane. I'm loving life, bubbling, buzzing, in my own little world. They took him out of that little nothing world and put him over there and totally changed his life."

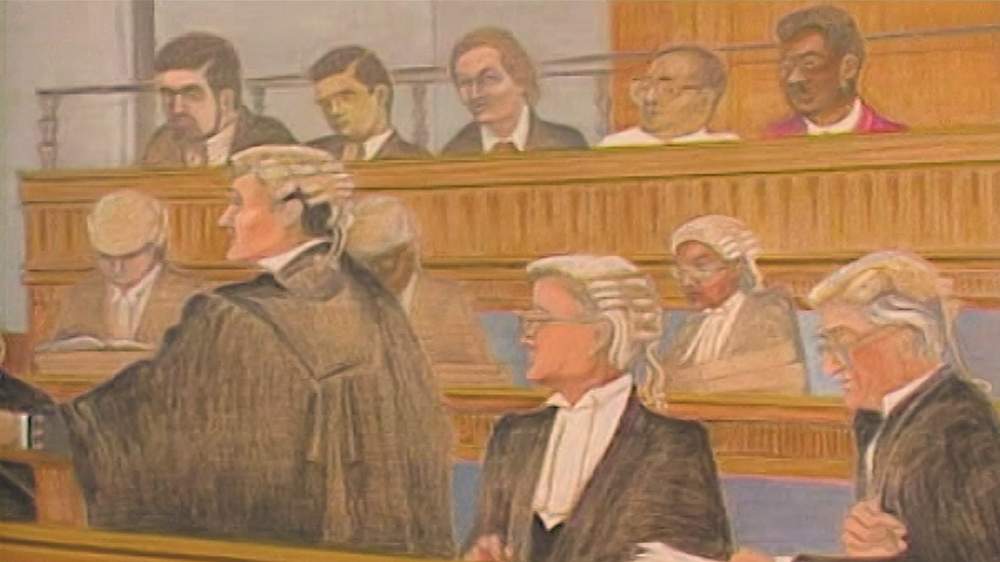

The first trial of the Cardiff Five began on 17 October 1989 in Swansea's crown court, a city not known for its diversity back then.

It seemed to be doomed from the start.

Five months later in its final few days, the trial was abandoned. The judge had died of a heart attack.

Three months later in May 1990, the second trial got under way.

David Elfer QC opened for the prosecution.

"Butetown," he said, "is a nocturnal, upside down, topsy-turvy world where people carry knives as part of their clothing."

It was an excoriation of the entire community.

Seasoned court reporters recall a "toxic", febrile atmosphere of fraught security, legal aggression, public gallery outbursts and outcries from the dock. Police were on the court roof top photographing everyone who attended.

The jury heard that the five accused men had killed Lynette to make an example of her over a drug debt.

The police presented a scenario in which all five men had somehow come together and made their way to the flat where they took it in turns to stab her to death.

Lynette's friend Leanne Vilday, one of four so-called witnesses to her murder

There were four key witnesses. Two of them were sex workers, Leanne Vilday, Lynette's friend, and Angela Psaila.

Both women, interviewed several times by police, said they knew nothing about the murder.

Then after nine months their stories changed dramatically. Now suddenly their police statements said they had been in Psaila's flat across the road.

They heard screams from 7 James Street and had run over to find out what was going on.

They alleged they had run up the stairs, pushed past "hard as nails" doorman John Actie, not known for being easy to push past, and saw Lynette being attacked in the flat.

"She stood no chance against them," Psaila told the jury. "They were standing around smirking.

"They were taking it in turns to stab her. She managed to lift herself up to the window sill. She was pawing at the window trying to attract somebody's attention."

The women said they too were forced to cut Lynette's throat and wrists, their involvement ensuring they keep quiet about what had happened.

The two other witnesses were two gay men - Mark Grommek who lived in the second floor flat of 7 James Street and Paul Atkins who was with him that night. They too had changed their story to one implicating all five men.

Their statements were shown to Stephen Miller when he was arrested. He insisted he knew nothing before finally cracking during five days of interrogation.

By the end he agreed with the police that he was in the flat with the other men.

The court heard that he had immediately withdrawn his 'confession'. This may have been given little credence at the time but before long, it would come back to haunt the detectives who had extracted it from him.

The eyewitness evidence was as flimsy as it was fantastical. Their testimony was riddled with contradictions, lies and discrepancies.

Their accounts were so chaotic it was not even clear who was actually at the murder scene.

The judge, who at one stage was rushed to hospital with an angina attack, told the jury they were unsatisfactory witnesses whose police statements were also "admittedly studded with lies".

All the accused men said they had alibis for that night and there was not a shred of forensic evidence linking them to the flat.

In November 1990 Stephen Miller was convicted.

Stephen Miller driven away from court

Tony Paris is given life with a 17-year tariff

Tony Paris was also found guilty - his cellmate, convicted armed robber and supergrass Ian Massey, claimed he had confessed to him.

Ronnie Actie was unanimously found not guilty.

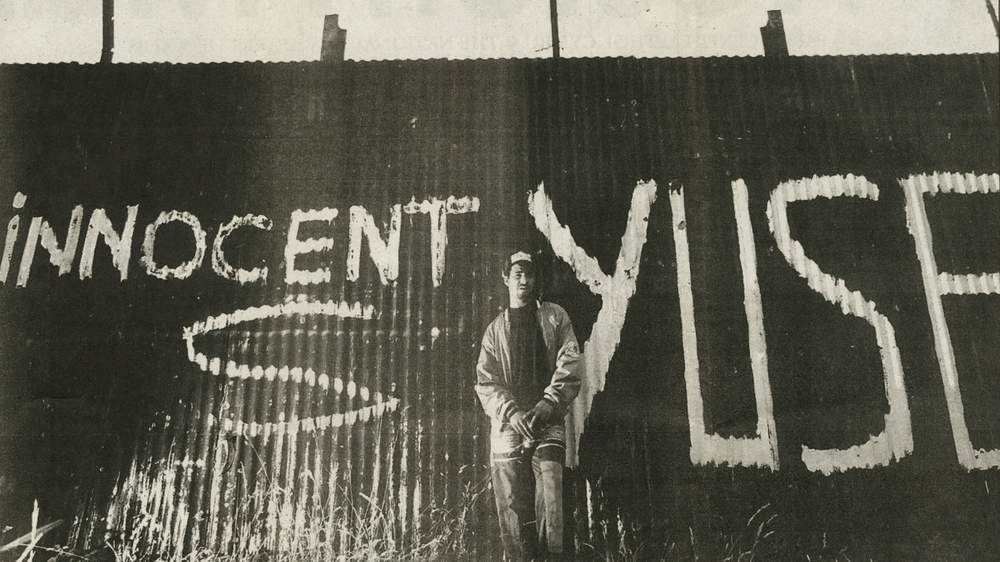

"The persons or person who killed Lynette White are out on the streets, they're walking the streets," he shouted. "They are innocent men in there."

The following day Yusef Abdullahi was also convicted despite 13 people confirming he had been working 10 miles away on a boat in Barry docks that night, an alibi the prosecution sought to undermine.

Yusef Abdullahi was working on board MV Coral Sea the night of the murder

"I wasn't even in Cardiff," he shouted, panic-stricken. "You took my life away from me… I am innocent."

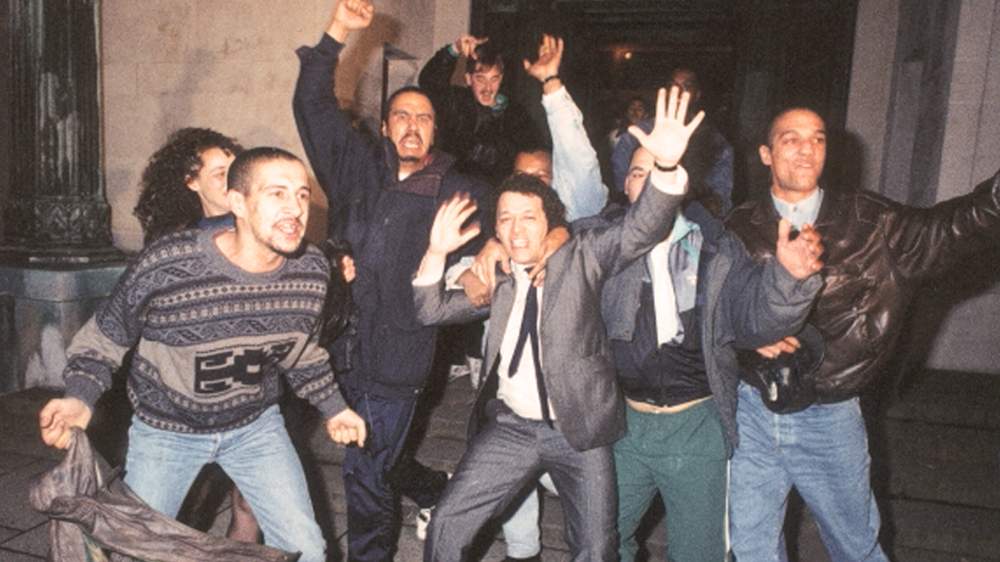

John Actie, so traumatised he was unable to walk unaided into the dock, was the last up. Unanimously not guilty.

Jumping down from the public gallery, his family dragged him out of the dock and carried him outside where breaking down he pleaded: "They're innocent! They're innocent!"

When asked how he felt, he cried: "I am bitter and I am broke."

The other three men were sentenced to life.

An exhausting and traumatic trial - at the time the longest in British history - was over.

After all the sentences had been passed the jury foreman simply sat and wept.

The real murderer must have thought he had got away with it.

The last time Stephen Miller had seen Lynette they had rowed. He says it was about her work and how it was impacting on their relationship.

Vehemently denying he was the pimp police had made him out to be, he has insisted that on many occasions he tried to persuade her to stop but it was the only work she knew and the couple fell into a pattern.

Yes, he admitted Lynette would give him money but he says he also had his dole money and cash from selling weed and doing odd jobs.

Stephen, who says he was never violent after serving a four-month term for GBH as a teenager, recalled breaking down on being told a body had been found which officers suspected was Lynette.

When asked if he would be willing to provide DNA samples, clothing, he had said: "Anything you want you can take, anything you want."

For the next few months, Stephen said he was in a "nightmarish daze", constantly going back and forth to the police station seeking updates on the murder inquiry and actively responded to requests by detectives to find out if any one in the area knew anything about Lynette's death.

Seven months after her murder, he returned to London to stay with his mother until he was arrested in December 1988 and succumbed to the "terror" of police questioning.

Four years later on 7 December 1992, Stephen Miller, Tony Paris and Yusef Abdullahi – by now known as The Cardiff Three after a campaign was launched to spread the word about their wrongful conviction - had made it to the Court of Appeal.

The tapes of Miller’s confession to the police – which had effectively convicted all three men – showed officers “bullying” and “beating him over the head verbally”.

Streetwise he might have been, but Miller had the IQ of an 11 year old.

He had been put through 19 interviews over five days of “psychological torture” the court heard. He had insisted 300 times that he knew nothing. Not once did his appointed solicitor interject on his behalf.

He finally cracked under an incessant charade of good cop-bad cop and acquiesced to whatever they said.

The interview tapes were played in court – they had not been heard at the original trial – to demonstrate the level of intimidation and bullying which belied the printed transcripts.

In his judgement freeing the men, Lord Chief Justice Lord Taylor said he was “horrified” by the tapes which showed the “worst example of police excesses”.

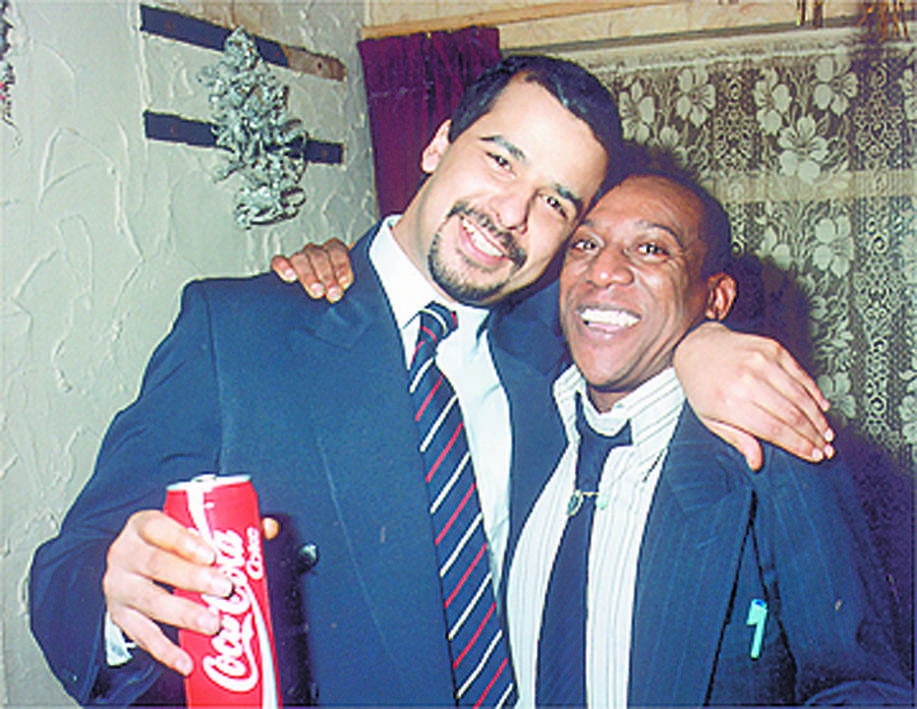

Yusef Abdullahi with brother Malik

“The interviewing officers could not have acted in a more hostile and intimidating manner… they had made it clear to Miller that they would continue to question him until they 'got it right',” he said.

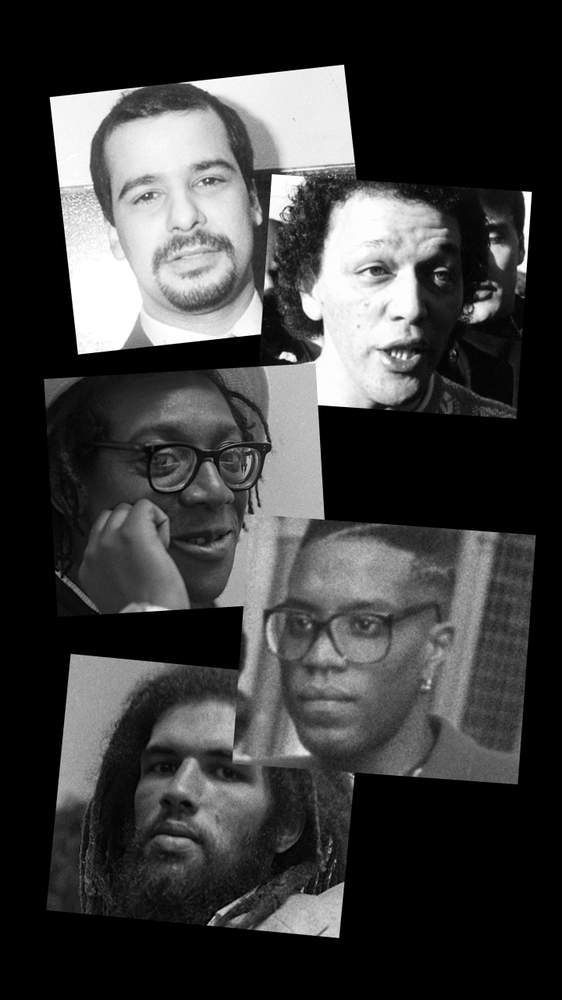

The work of the Free the Cardiff Three campaign – run by brothers of two of the defendants Lloyd Paris and Malik Abdullahi – was at an end.

They had travelled the country in a bid to win support, highlighting gaping holes in the police case.

In the run up to the appeal, black newspaper The Voice took up the cause then broadsheet newspapers began to take notice followed by TV programmes - Channel Four’s Black Bag, BBC Wales’ Week In Week Out, and the BBC’s Panorama.

Tony's brother Lloyd Paris with Yusef Abdullahi's brother Malik centre, left

Also in the months leading up to the men’s release, the American civil rights activist and Baptist minister Reverend Al Sharpton arrived in Butetown to lead a protest march past Cardiff prison, through the city centre to city hall.

Addressing a rally of supporters through a loud-speaker, he said: "I'm happy to be here today to join people of all races and colour to talk about the injustice that has happened to these three brothers.

"It is clear that it is only because of their social, economic and racial status that they are in jail."

Gerry Conlon, one of the Guildford Four, had also visited the area to highlight the “ludicrous and disturbing” case.

Gerry Conlon, who spent 15 years in prison after he was wrongly convicted of the IRA Guildford pub bombing, arrives in Butetown

First night of freedom for four years and one day: Yusef Abdullahi and Tony Paris at a welcome home party

It had all paid off.

Tony Paris was now a free man but it was bitter sweet.

Just weeks before, he had been handcuffed and escorted by guards from Wormwood Scrubs, to say goodbye to his dying father, Arthur. He died before seeing his son vindicated.

On his conviction he insisted his wife, the mother of his young son, divorce him. The world he was returning to was a very different one.

South Wales Police announced they would not re-open the investigation and no disciplinary action would be taken against any officer involved.

By so doing, rumour and speculation about the men’s guilt was rife.

In September 1996 Lynette’s father knocked on John Actie’s front door armed with a sawn-off shotgun. Armed police sealed off the area.

“If I hadn’t looked out of the kitchen window and seen him,” John says, “I would have opened the door and I'd have been blown away.”

Given a suspended jail sentence, Mr White told the court: “I’ve been abused and laughed at for the last seven years after these men were freed for my daughter’s murder which in my mind they undoubtedly committed. I had had enough and just exploded.”

Mr White died in January 2001, aged 55, after falling down stairs at his home.

Nine months later his son, Terence, Lynette’s brother, was found dead. He was 28. His family said his life was blighted by his sister’s murder.

Neither lived to see the justice they had been denied for so long.

In September 2000 police re-opened the Lynette White murder case following a cold case review.

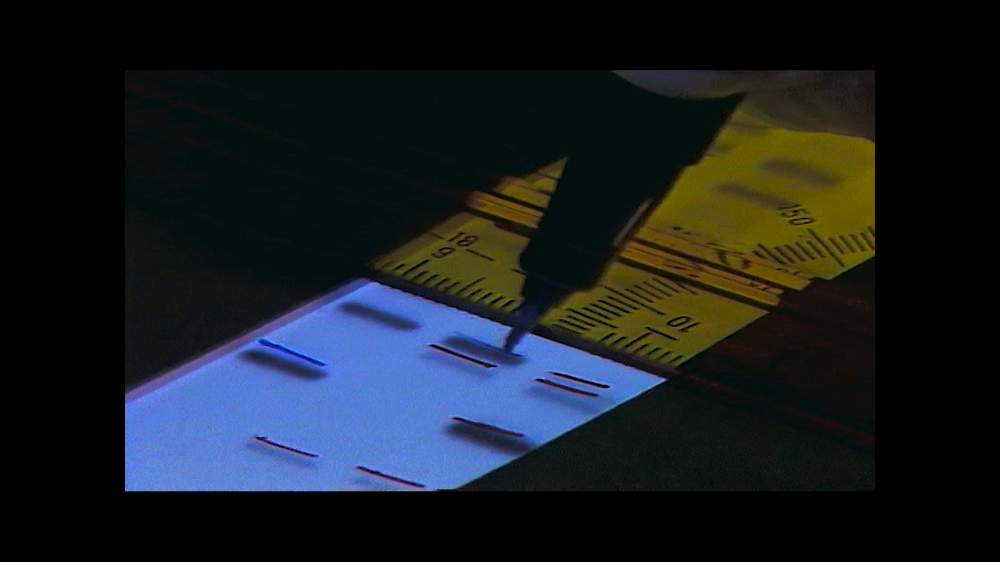

Detectives worked with a forensic science team led by world-renowned Angela Gallop. A tiny piece of bloody cellophane had been found near the body. They had the beginnings of a DNA profile.

The hunt was on for Cellophane Man.

But they needed more. And 7 James Street was about to give up its final secret.

A skirting board was removed and under six layers of new paint, there was a spot of blood. It was Cellophane Man's.

Blood on the front door was also his. The final proof was his blood on Lynette's clothing.

Lynette had been dragged to where the majority of the attack probably took place.

The murderer had cut his hand when it slid down the hilt of his knife and onto the blade during the ferocious attack; he then blundered out of the flat in the pitch black, down the stairs and fumbled to find the catch on the front door.

But who was Cellophane Man?

A mass DNA screening and searches of 140 police databases around the world yielded nothing.

In what has been roundly applauded as "outstanding" and painstaking detective work, an officer noticed a pattern in the profiles, a rare DNA marker.

He had spent months scrutinising print outs from the national database. A 14-year-old boy, who had been arrested for joyriding in Cardiff, stood out; his DNA was a partial match.

They inquired about his older male relatives which included a 38-year-old uncle.

He was contacted by the police and put on surveillance pending the results of forensic tests.

Officers burst into his house when he had been seen buying quantities of paracetamol. He had taken an overdose of 64 tablets.

"Just for the record I did kill Lynette White," he said. "I've been waiting for this for 15 years. Whatever happens I deserve it. I sincerely hope to die."

He was rushed to hospital. He survived.

At the time of the murder Jeffrey Gafoor had been living above a corner shop run by his sister and her husband, in the Cathays area of Cardiff, three miles from the docks.

A loner who collected knives and antiques and was prone to binge drinking, he had been working at a warehouse loading lorries.

At the time of his arrest, he worked shifts as a security guard at offices in Cardiff.

Described as "intelligent", he had no friends and had cut ties with his entire family in the years following the murder.

Blanking the murder from his memory, he lived a reclusive life, renting a house in the village of Llanharan, near Bridgend, south Wales.

The murder at James Street was apparently his first crime.

Remarkably he had only one conviction after the murder, for assaulting a colleague in 1992.

It is highly likely that Gafoor would never have been caught had it not been for his nephew's arrest.

His recollection of what happened was "dream-like, fuzzy", he said, but he recalled he had lashed out at Lynette after changing his mind about having sex. He had asked for his £30 back and she had refused.

On 4 July 2003 Gafoor pleaded guilty. He had acted alone and apologised to the Cardiff Five for their ordeal.

For the first time in history a miscarriage of justice had been solved by the conviction of the real killer.

That was cold comfort for Yusef Abdullahi.

Speaking outside Cardiff Crown Court as Gafoor stood in the dock, he said: “I didn’t want to go in there because I’d have ripped his head off.

"Then I would have been up for a murder because I’m just really bitter towards him."

Sentenced to life, Gafoor was given a 13-year tariff - the minimum he must serve before he could apply for parole. It was less than the tariffs given to two of the Cardiff Three.

Gafoor's conviction now raised serious questions about the eyewitness testimony of what happened in James Street presented at the original trial.

In 2008 three of the four people who helped convict the men - Mark Grommek, Leanne Vilday and Angela Psaila - admitted they had made the whole thing up after being "harassed into lying" by police.

Paul Atkins was deemed mentally unfit to stand trial.

The three said they had been threatened with being convicted of the murder themselves.

The court was told that Vilday was told her baby son would be taken away and was shown photographs of abused children in care.

Psaila had an IQ of 55 and was described as one of the most vulnerable members of Cardiff society.

Grommek was also vulnerable because of his sexuality as “in 1988 there was rather more intolerance of gay people than is the case now”.

The judge Mr Justice Maddison said: "It's been submitted on your behalf, accepted by the prosecution and I accept it myself...

"You were seriously hounded, bullied, threatened, abused and manipulated by the police during a period of several months leading up to late 1988, as a result of which you felt compelled to agree to false accounts they suggested to you."

The three were jailed for 18 months each.

One of the most eminent barristers in the country, Lord Carlile QC, defended Leanne Vilday.

"The sheer wickedness and dishonesty of the police and remorseless systemic corruption in this case is difficult to believe, but it's true beyond a doubt and it is accepted by the prosecution," he said.

It would be "an utter scandal", he said, if none of the police officers involved in the case were brought to trial themselves.

In a series of dawn arrests, a number of serving and retired officers were pulled in for questioning.

Following a six-year investigation, eight retired officers were in the dock charged with perverting the course of justice. A trial of four other officers was due to begin the following year.

Graham Mouncher, Richard Powell, Thomas Page, Michael Daniels, Paul Jennings, Paul Stephen, Peter Greenwood and John Seaford denied conspiring to pervert the course of justice. In addition Mouncher denied lying under oath in court.

Facing perjury charges were two civilian witnesses from the original trial, Violet Perriam, whose statement had put John Actie near 7 James Street on the night of the murder, and the discredited supergrass Ian Massey who claimed Tony Paris had confessed to him.

All pleaded not guilty.

The prosecution alleged the detectives had "manipulated, moulded and even completely fabricated" evidence, that they had acted "corruptly together and with other police officers to manufacture a case against the five men".

"The police had moved away from investigating a murder and they were instead busy trying to implicate people in that murder, people who were actually completely innocent of that murder," the jury was told.

Despite the fact that Gafoor insisted he acted alone and had never met any of the five men originally accused of the murder, the police's defence would not have it - they were involved, they alleged.

Under the law of court privilege which protected the defence from being sued for defamation by the innocent men, their theory was that there were two attacks - Gafoor had stabbed Lynette but not fatally and then somehow the five happened upon the scene and took over.

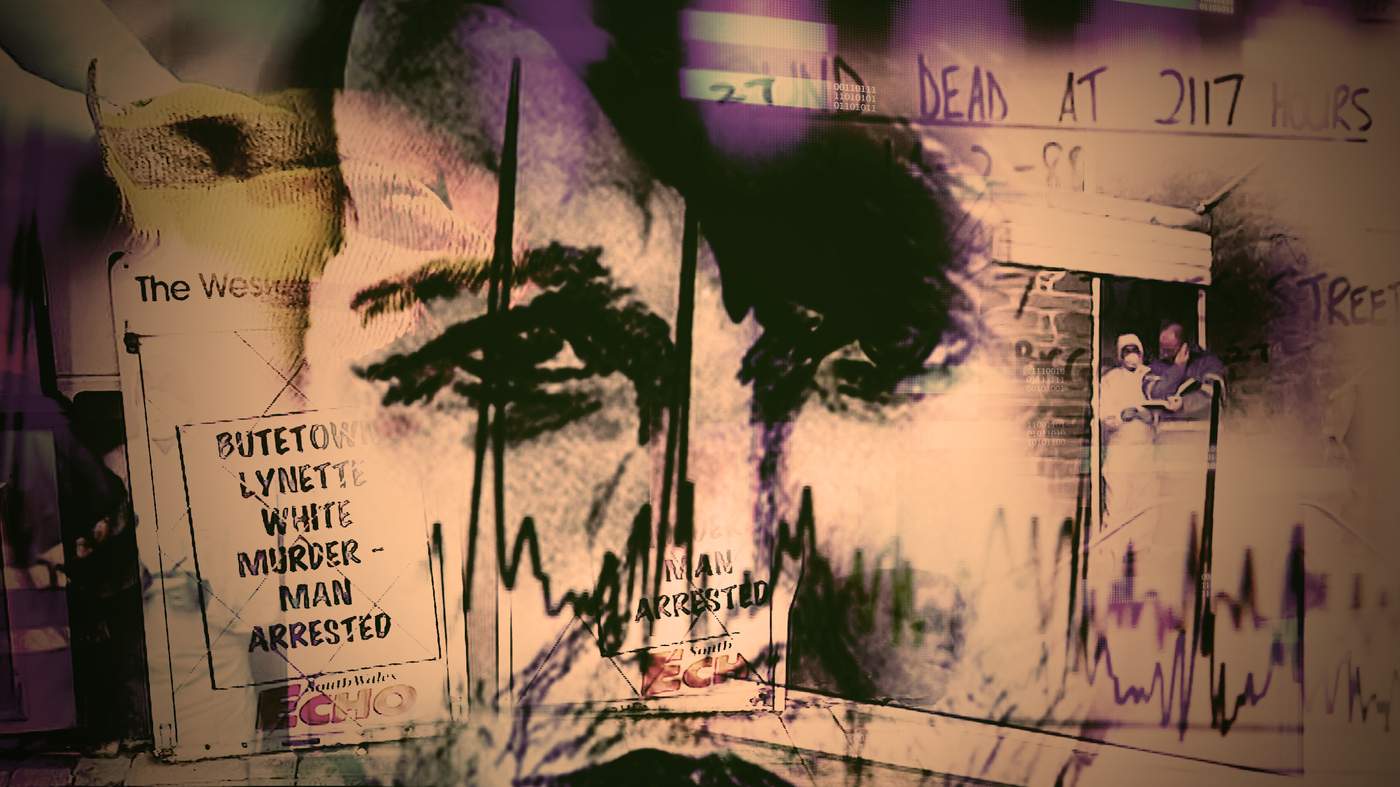

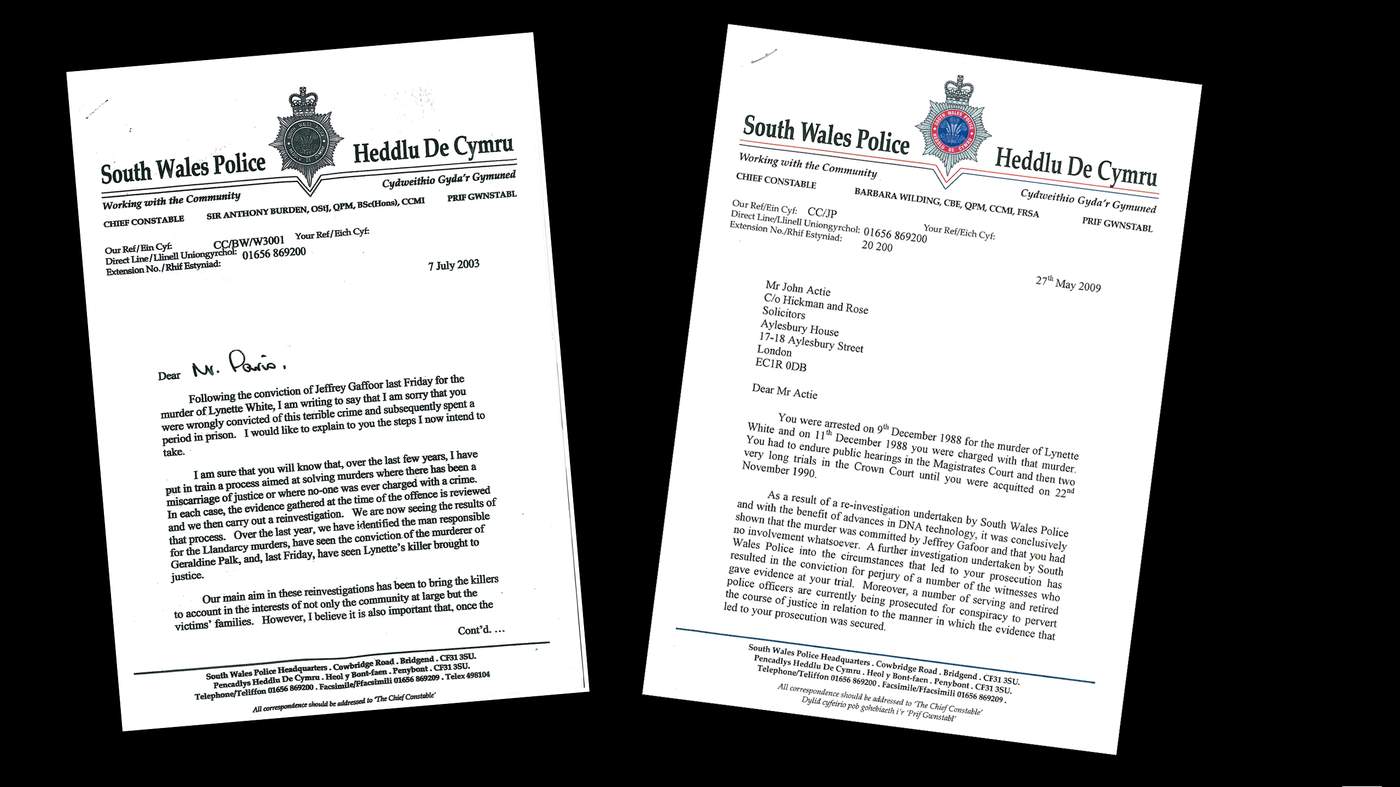

It did not seem to matter that they had been acquitted, Lynette's real murderer convicted, that not a single shred of evidence, forensic or otherwise linked any of the men to the murder scene or that they had received public and written apologies from two chief constables.

The surviving members of the Cardiff Five were called as witnesses - John Actie, Tony Paris and Stephen Miller.

Perhaps most shockingly of all in the 30-year saga, they were effectively put on trial a second time during intense and prolonged cross-examination and without any defence.

"It was happening all over again," Tony Paris says. "I was called as a witness and thought I'd be there for a few hours and then go home.

"Four days I was there. We were being accused and tried all over again."

During cross-examination John Actie said: "You keep accusing me of being there. I was acquitted. It is them who fitted me up… I wasn't there… It seems like I am on trial."

Then in December 2011 after five months of evidence, the £30m trial collapsed in dramatic and controversial circumstances.

It had become clear as the trial progressed that the process of disclosure was failing.

Disclosure is the production and sharing by the prosecution of documents relevant to the case.

This includes any information that either undermines the prosecution's case or potentially assists the defendants in their case.

After several warnings by the judge, the prosecution was given one last chance, a litmus test, to prove they had handled the paper work correctly.

But copies of a crucial set of four files required to prove the prosecution's competence regarding disclosure of material could not be found.

Detective Chief Superintendent Chris Coutts

The judge heard evidence alleging proof that one of the files had been destroyed on the orders of the officer leading the police corruption investigation Detective Chief Superintendent Chris Coutts.

Following five months of evidence, the judge announced that a fair trial could not be guaranteed and abandoned the trial.

All defendants were declared not guilty.

Then in an extraordinary twist, the missing files were found seven weeks later in a cardboard box with other documents relating to the case in the offices of the police corruption investigation team.

Calls for a full public inquiry into what went wrong were resisted.

Instead the then Home Secretary Theresa May ordered an independent review led by Richard Horwell QC.

Its conclusions were published in July last year.

Horwell QC described the Cardiff Three convictions as "one of the worst miscarriages of justice in our criminal justice system".

On the disclosure issues which led to the collapse of the police corruption trial, he said there had been errors amounting to "an embarrassment on a national scale".

But, he went on, "suspicion that the trial collapsed due to yet further police corruption has not been supported by the evidence".

"It is human failings that brought about the collapse of the trial, not wickedness," he concluded.

Despite criticism that South Wales Police was put in charge of investigating its own officers, it is widely acknowledged that Chris Coutts led a competent and efficient investigation in bringing the retired officers to court.

But the handling of the disclosure, a complex task involving around one million pages of evidence, was wholly incompetent.

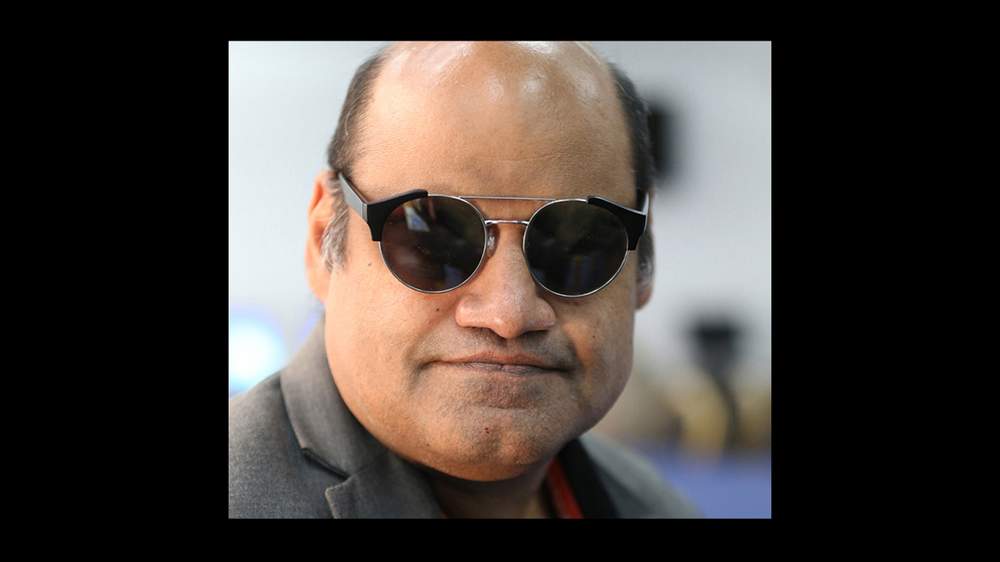

"The prosecution had predicted there would be an attack on disclosure," says journalist and author Satish Sekar, who has closely followed the case since 1991 and written three books about it.

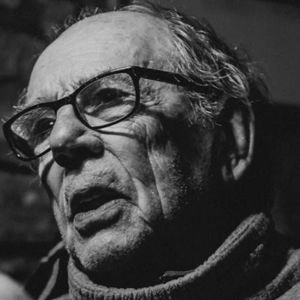

Satish Sekar

"If you've predicted that how do you get caught with your pants down like that? Absolutely ludicrous."

"What stands about the Cardiff Five," he adds, "is that it's very rare for so much to go wrong in the one case.

"Aspects of it you'll find in virtually every single miscarriage of justice. What is rare is that it all happened in the one case."

In 2015 the eight exonerated police officers sued South Wales Police for damages. They lost the case.

To say John Actie is bitter is an understatement. His relationship with the police, he says, is as fractious as ever and he has made numerous complaints about harassment.

"My life has been ruined by what the police did," he says. "I have been attacked, had people come up and call me a murderer when I'm out. I've been sent cards on Valentine's Day saying 'remember the 14th'. This will not leave me until I'm in my grave.

"My family has suffered, all our families have suffered. Our one chance of closure and they lose some papers?"

Speaking in 1990s, Yusef Abdullahi, who undertook an 18-month speaking tour on miscarriages of justice after his release, during which he met high-profile figures such as U2 front man and philanthropist Bono, told how he had collapsed from nervous exhaustion and woke up in a psychiatric bed.

"I was there for several months and people keep telling me to take it easier," he said. "But the whole situation had got to me. I mean one minute I was in jail, the next I'm sitting eating with Bono.

"Until it happens to you, no one can have any idea what it's like to be convicted for a murder you didn't commit.

"We've been really messed up by what we've been though. We needed counselling but no one offered us any help. It did my head in."

He did live to see Lynette's killer jailed but died of a burst ulcer in January 2011, aged 49.

Ronnie Actie died in 2007 from deep vein thrombosis also aged 49. He had been virtually living in a garden shed.

"Why the police wanted me off the streets for the rest of my life? I don't know," he said in an interview with BBC Wales. "I'd love to know all those reasons. One day they'll come out."

Tony Paris has a theory.

"The police thought the community was hiding something but people aren't talking," he says.

"So, this is my opinion, they thought 'we'll take him and him and him'… All of us apart from Miller were from big docks families. If anybody knows anything, now they've got to talk to get these guys out.

"The entire legal system, not just the police, were involved in what happened to us.

"It changed my life. I went from being an extrovert in clubs and pubs to an introvert where I don't go out. I try to hide it when I do go out, but then I withdraw because I'm scared. I don't trust people.

"I try to find suitable words to put my feelings across. But when you think about it, there is no word, there is no word in the dictionary in any language that you can find to truly put across how you feel, it's unspeakable."

The case, estimated to have cost South Wales Police in excess of £100m, scarred the reputation of a police force which had four other recent miscarriages of justice on its record.

The so-called Cardiff Newsagent Three were wrongly convicted for the murder of newsagent Phillip Saunders. They spent 11 years in jail before being released.

After serving seven years for murder, the Darvell brothers were freed by the Court of Appeal in 1992 after it heard claims that detectives doctored confession statements and notes and suppressed scientific evidence.

The following year Jonathan Jones was found to have been wrongly convicted of the murder of his in-laws Harry and Megan Tooze at their south Wales farm.

Annette Hewins' conviction was quashed in 1999. She had been serving a 13-year sentence for arson with intent to endanger life following the death of 21-year-old Diane Jones and her daughters Shauna, two, and Sarah-Jane, 13 months.

Police accepted in 2006 she had no part in the murders. She died last year aged 51.

But it is without doubt the Lynette White murder inquiry that stands out as South Wales Police's, if not the UK's, most notorious case.

Eligible for parole since March 2016, the prospect that Jeffrey Gafoor could be freed at any time is not an easy one for Lynette White's family or for those branded with his crime for so long.

On the 30th anniversary of Lynette's murder there are calls for a change in the law so criminals who knowingly allow miscarriages of justice to unfold before they are convicted, can be dealt with more severely.

"There certainly were questions raised in a number of places about whether the sentence was proportionate to the nature of the crime and the fact that several innocent people spent time in prison as a result of Gafoor not coming forward and not admitting the case at an earlier stage," says South Wales Police and Crime Commissioner Alun Michael.

South Wales Police and Crime Commissioner Alun Michael

"I can't answer those questions but I think they are legitimate questions and it's a challenge to the criminal justice system to ensure that all factors can be taken into account in the sentencing process in future."

But a stain remains on South Wales Police which, says newly installed Chief Constable Matt Jukes, has served to forge a determination for change.

Speaking on the anniversary of Lynette White's murder, he says: "The learning we've taken from the murder of Lynette White and the original investigation has led us to review many other historic cases and has led to convictions in several of those.

"So, the case itself has driven a change in the organisation and brought about justice for other victims.

South Wales Police Chief Constable Matt Jukes

"For young officers today and many members of the community this case is something that they're aware of in the history of the organisation.

"It has truly deep resonances for all those affected by it and it's somewhat now in the DNA of the force I've got to say.

"Our determination not to fail in this way again steels my resolve every day to make sure our investigations are of the highest quality, professionally, technically, ethically, that they can possibly be.

"So I don't think even though this is an event that took place 30 years ago, it will leave the psyche of this organisation and its leadership for another generation."

On the surface at least the untidy past of Cardiff's docklands has been successfully swept away, transformed into the trendy waterfront vision conceived in the late 1980s replete with serviced apartments, bars and restaurants.

It is also home to the Welsh Assembly's Senedd.

7 James Street (end building on right) close to the Wales Millennium Centre

Now a smart rental above a vaping shop, 7 James Street is a stone's throw from the city's Millennium Centre, a thriving venue for opera, theatre and visiting West End shows.

Once the beating heart of one of the world's most famous docks, its procession of stately buildings of ship brokers and chandlers and its exotically decorated shop fronts, is no more. The street is a ghost of its former self.

The vestiges of the old Tiger Bay community are now a minority within Butetown, says Neil Sinclair, an author of three books on the history of the area.

He witnessed the corrosive effect the Lynette White murder inquiry had on the community, one from which it has never fully recovered.

"Our general feeling as a community is that over the decades they wanted to eradicate us from Welsh memory and almost succeeded except for the fact that I've written down our history."

"But," Neil adds, "our ancestors, they didn't live in vain and they're going to come out, their ghosts are going to rise and our proud history will be given the recognition it deserves."

The surviving men caught up in one of the biggest scandals in recent history, never regained the peace they had taken for granted before being branded with the stigma of what happened at 7 James Street on St Valentine's Day 1988.

Immediately on being freed from jail, Tony Paris had said: "They wanted anybody for that murder. They thought we were anybodies but we were somebodies."

He may well have been speaking for the entire community of Butetown, and for Lynette White, who had been dehumanised for so long as "the Cardiff prostitute".

The case continues to haunt Stephen Miller who has experienced depression, anxiety and agoraphobia not to mention his regret at not being there to protect the woman he said he loved very much.

"She's helped me, she's the one that's kept me strong," he said of Lynette. "When I think about the case I think about her. Because this is all about her, it's not about us, it's about her."

Had she lived Lynette White would have celebrated her 50th birthday last July.

She had lost her way but might well have in time, like countless other troubled 20 year olds, reached a point of maturity and confidence to turn it all around.

Her appalling death meant she would never get the chance.

The name of a vulnerable young woman who craved only love but was exploited by every man who paid for her youth, beauty and fragility, was fated not to be forgotten.

It is not the legacy she or her loved ones would have wished for, but Lynette Debra White, born Wednesday, 5 July 1967, was destined to embody what is branded by some as "the biggest scandal" of recent legal history, an injustice the scale of which is never likely to be repeated in the UK, ever again.

Credits

Author

Ceri Jackson

BBC Wales Investigates

Web production

Ceri Jackson, Philip John, Sophie Mutton

Video editing

Philip John

Photography

David Hurn, Magnum Photos

Walesonline

Press Association

The White family

Simon Campbell

Rosie Hallam/N&S Syndication

John Actie

Tony Paris

Neil Sinclair

Alamy

Foomandoonian

Nick Townsend

Built with

Shorthand

Publication date

14 February 2018

All images subject to copyright