The five photographs that (you didn’t know) changed everything

You won't find these photographs in any glossy coffee table book. They’re not art, and the people who took them can’t be found in a Photographers’ Hall of Fame. Yet all five of these images have had an enormous impact on our world. Here’s how.

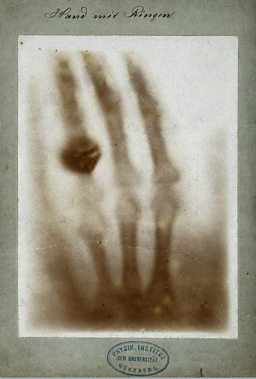

Anna Bertha’s left hand

X-rays have become so much a part of our daily lives that we no longer really think about them – or even think of them as photographs. But when the first X-ray came into being it was shocking, singular and quite unfathomable.

Here it is: the 1896 photograph of Anna Bertha Ludwig Röntgen's left hand that quite clearly shows its subject’s bones, joints and soft tissue – even her bulky wedding ring (the person who took the X-ray was her husband, Conrad Wilhelm Röntgen, who wouldn’t trust the details of his research to a paid assistant).

This image may have signalled the beginning of medical radiography, but for the public it was a great source of alarm. An instrument that could see beneath the skin? What did that mean for privacy? It’s easy to see why this photograph caused the same kind of public reaction as the introduction of the TSA body scanner in 2007.

Still, patients would soon come to concede it was an improvement on the old way of doing things. After all, up until this moment, doctors could only see what was going on inside bodies by cutting them open.

Hear more from Kelley Wilder, Reader in Photographic History, De Montfort University, Leicester.

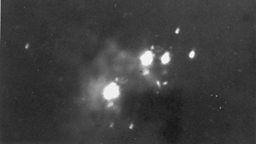

The Nebula in Orion

Today, high-res photographs of nebulae or galaxies saturate our culture to such an extent that they are almost kitsch, adorning student walls everywhere. But when Henry Draper took the very first pictures of a nebula, it was one of the greatest achievements of photography to date.

Photography had been around for 40 years by the time this image was captured in 1880. Photographers had already pictured the moon, sun, stars, comets and even some planets – but not celestial nebulae, because their light was just too faint. It took a full 51 minutes of exposure time to capture this image, and even then, its critics argued that pencil drawings of the same nebula were better than the photo.

Still, as the first photograph of its kind, this image opened up countless new lines of inquiry and debate around the types of raw materials that went into the formation of Earth and the solar system. Its existence raised questions not just about the size of the universe, but about the origins of humanity itself.

Hear more from Omar Nasim, lecturer in the School of History at the University of Kent.

The Dogon fields

Have you ever looked out of an aeroplane window as you come into land? Seen the houses, roads, fields and buildings, and wondered about what it would be like to live there?

Marcel Griaule was a French ethnographer who had trained in aerial photography during World War One. He took this bird’s-eye-view photograph in the mid-1930s during his fourth visit to the Dogon, a secretive people who carved their homes out of the sandstone Bandiagara cliffs of modern-day Mali.

Griaule marveled at the beauty and harmony of the Dogon’s rituals, myths, and ways of living. He argued that the landscape, as seen from the air, could reveal secrets about the lives of its inhabitants that could teach Westerners how to build a happier society. It was clear that the Dogon lived in homes that reflected their landscape as well as their family structures and their values.

This photograph paved the way for a generation of Western architects, planners, and sociologists to develop a new, more humanistic approach to the built environment.

Hear more from Jeanne Haffner, lecturer in the Department of History and Science at Harvard University.

The Broom cottages

This photograph of an unremarkable row of cottages doesn’t stand out at first. It may not even be Facebook material. So why does this image mark the moment when documenting daily life became a pastime for everyone?

The man who took the photo, W. Jerome Harrison, was a Victorian polymath who launched a grand scheme for documenting the country's visual history. Under his influence, hundreds of amateur photographers took photos of buildings that were important to them – not because they were grand, important or well-known, but because they were typical of their area and represented what life was like at the time. Today, libraries and museums are full of these exhibits, which form the backbone of many local history collections.

Nowadays organisations like Wiki-buildings and English Heritage document the visual history of buildings on a much grander scale. But the act of allowing ordinary people to define what matters about the past began with Harrison – and changed the way in which the nation viewed itself.

Hear more from Elizabeth Edwards, Research Professor of Photographic History and Director of the Photographic History Research Centre at De Montfort University, Leicester.

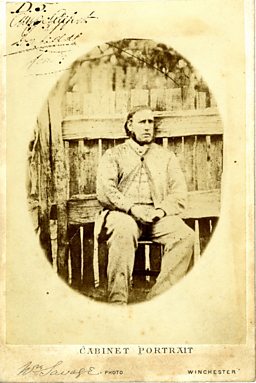

The Tichborne Claimant

In 1866, a butcher sat for his photograph in the remote town of Wagga Wagga, Australia. Three years later, the resulting image had Britain transfixed. It would become central to the longest legal battle in 19th-century England, sparking debates about evidence, the law, ethics and facial recognition that have continued ever since.

The subject of the photo was known to his neighbours as Tom Castro. However, he was born Arthur Orton; a native of London, he had emigrated to Australia in 1852 to start a new life. And, just over a decade later, he had this photo taken in an attempt to prove his identity as Sir Roger Tichborne, an English aristocrat who had disappeared off the coast of Brazil ten years before. No wonder he looks a bit shifty.

Amazingly, the photo convinced the missing man’s mother, Lady Tichborne, that Tom/Arthur was indeed her son, and with her financial support he sailed back to Europe. When his “mother” died around a year later, he launched an inheritance claim against the rest of the Tichborne family.

The resulting legal trial was the longest and most expensive in British legal history to date, with the photograph a central piece of evidence. The image itself raises questions of huge importance: is photography a tool of empowerment, or of surveillance and control? And can it be used to establish truth from fiction?

These questions are still with us today – and they were presented to us for the first time in an albumen photograph of a slaughterman from Wagga Wagga.

Hear more from Jennifer Tucker, Associate Professor of History and Science in Society at Wesleyan University, USA.

The Essay

-

![]()

The Essay

Leading writers on arts, history, philosophy, science, religion and beyond.

-

![]()

The Proms 2016

Events, line-up and features around the world's biggest classical music festival.

-

![]()

The Listening Service

Tom Service presents a journey of imagination and insight, exploring how music works.