Could a new understanding of how cancer starts lead to personalised risk tests?

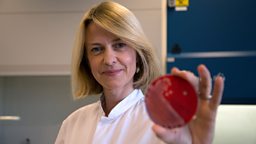

At University College London, Professor Martin Widschwendter and his team have been studying how cancer starts, and it’s based on a relatively new understanding of our genes.

We’ve known for decades that the genes we inherit are an instruction book to tell the cells in our body to do certain things. But in recent years we’ve started to understand the more complicated aspect of this: how each cell type reads different instructions from this master plan at different times; in other words, how the same instructions can make a kidney cell and a muscle cell. It’s down to tiny changes in the “packaging” of our DNA that can make some sections of the instruction book unreadable at times, and one way that this can happen is called “DNA methylation”.

By studying DNA methylation, the team at UCL have made discoveries that could help us in the fight against cancer. They looked at cells from women with breast cancer and cells from women without it, and discovered that key changes happen in the DNA of cells before they become cancerous – tiny changes to the DNA methylation of certain genes in cells greatly increased the risk of those cells becoming cancerous (when the DNA code itself becomes permanently damaged). Recognising this unique pattern allowed them to identify women who were likely to develop breast cancer in the future; but this wasn’t restricted to breast cancer – Martin believes that this tool could be used to predict the risk of ANY cancer as ‘signature’ DNA methylation changes have been identified for many cancer types now. But even more importantly, the DNA methylation changes are reversible – allowing you to reduce your risk of cancer again.

We now understand that the things we know can increase your risk of cancer, such as smoking, alcohol, or obesity, are changing your DNA methylation. However, if you stop smoking, the DNA methylation can go back to its safer form – explaining why your risk of cancer falls again in those who quit smoking.

If Martin’s test can predict the likelihood of cancer years before it actually develops, it gives people years to change their lifestyle before they develop cancer; it would act as a kind of early warning system. And this is Martin’s great hope – that his test can do for cancer what cholesterol and blood pressure tests have done for cardiovascular disease. By using these tests as warning indicators for cardiovascular disease, we’ve cut deaths from that illness in half. Martin’s test would in theory allow a GP to take a blood sample from their patient and that would give them a personalised cancer risk assessment – and he hopes it will be available by 2020.

Martin’s test could also be used to assess whether or not cancer treatments are working – by monitoring changes in DNA methylation patterns through the course of a treatment, we might be able to evaluate how effective the treatment is.

-

![]()

How we used Martin’s DNA methylation test to look for changes in our volunteers’ blood samples in our big turmeric experiment.

Does turmeric really help protect us from cancer?